Tom Waits’ wheelchair-bound bum says it best in Terry Gilliam’s The Fisher King when he explains that homeless people function in society as “moral traffic lights,” the mere sight of them keeping “normal” people on the straight and narrow. As ever with Gilliam, the monologue delivered by this character is a scathing critique of modern society, but it also provides a handy description of on-screen representations of homelessness.

Being homeless is one of our deepest fears, so it’s perhaps understandable that most of us would prefer not to engage with a destitute character. As a general rule mainstream cinema tends to revert to cliché when telling stories of social exclusion. More often than not, films featuring homeless characters rely on colour-tinted flashback sequences to provide a neat and tidy explanation for the protagonist’s current situation. This lends an emotional distance, affording the viewer the luxury of being able to take stock and think, ‘Well, that could never happen to me…’

Stereotypes abound in these films. Homeless protagonists can be divided into three distinct types: inherently tragic characters such as Jack Nicholson’s Francis in 1987’s Ironweed and the junkie couple in 2014’s Shelter; damaged geniuses like Jamie Foxx’s classical musician in The Soloist from 2009; and the freewheeling tramps of 1986’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills and the forthcoming Hampstead. The problem with these depictions is that cinema has a tendency to imbue everything it depicts with a dusting of glamour – as the Guardian critic Stuart Jeffries observes: “We might try to think about the gutter but we end up just looking at the [movie] stars.”

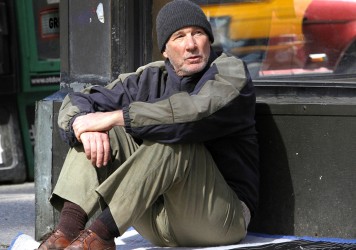

For filmmakers, then, to truly place the viewer in the shoes of a homeless person requires the courage to use non-traditional storytelling techniques. Oren Moverman’s Time Out of Mind, released in UK cinemas last week, has virtually nothing in common with previous films featuring character living in ‘reduced circumstances’. The superficial melodrama of a film like Shelter is replaced by an insistence on the monotony and stasis of the homeless experience. Much of the narrative is given over to long takes of Richard Gere’s George simply being still as the world carries on around him. Moverman also eschews the mawkish edification of the The Soloist. The rare moments of humour arise out of the characters’ apparently spontaneous riffing with one another, and George’s attempts at charm, which includes a brief flirtation with a kind nurse, reveal the true depths of his desperation.

The reason for George’s situation is only ever hinted at – indeed we are unceremoniously plunged into his story, left to grasp at whatever narrative clues float past on the fast moving tide of the New York streets. We meet George as he is woken from an awkward slumber in an empty bath tub in an abandoned apartment. Forced to leave, he has nowhere to go but the streets. From his look of confused resignation it’s clear that this is not an unfamiliar occurrence. There is little in the way of conventional backstory or exposition, and George essentially remains a mystery for the first two thirds of the film.

Time Out of Mind is a film that consciously avoids condescension. The idea of a single traumatic event providing the catalyst for the character’s inability to function in society is less important than submerging the viewer in the existential symptoms of homelessness. Moverman and Gere have created an immersive experience that succeeds in giving us a taste of what author and critic John Berger terms the “fragmentation” of homelessness in his 1984 book ‘And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos’:

“Originally home meant the center of the worldnot in a geographical, but in an ontological sense. A home was established “at the heart of the real.” In traditional societies, everything that made sense of the world was real; the surrounding chaos existed and was threatening, but it was threatening because it was unreal. Without a home at the center of the real, one was not only shelterless, but also lost in nonbeing, in unreality. Without a home everything was fragmentation.”

Visually, Moverman and cinematographer Bobby Bukowski draw inspiration from the work of New York photographer Saul Leiter. Like Leiter’s pictures, the frame in Time Out of Mind is often ‘layered’, with George shot from afar through panes of weathered glass. These shots create a distancing effect that allow us to observe George from a voyeuristic vantage point, while placing him in a disordered composition that reflects his state of mind. The fragmentation of the image manifests his sense of confusion, of being adrift. In his insightful piece on Film Comment, Michael Sragow argues that, combined with the elliptical narrative, this aesthetic approach makes the film feel “like a patchwork quilt left in patches,” but according to Berger’s definition of homelessness, this collapse of composition is precisely the point.

The sound design is even more powerful in evoking the splintered psychology of a homeless existence. George’s life on the streets is set to an incessant, oppressive cacophony of traffic, industrial noise and private conversational speech in some 20 different languages. This auditory assault imbues the world of the film with a vertiginous, hallucinatory feeling.

What really makes Time Out of Mind unique in its treatment of homelessness as an issue, however, is the compassion it strives to engender. By making the invisible visible, Moverman ensures that the very fabric of the film refutes George’s despairing lament: “I’m nobody. I don’t exist.”

Published 9 Mar 2016

Richard Gere channels the bruised (in)dignity of life on the streets of New York City in this thoughtful drama.

A new screening programme asks vital questions about how Britain’s travellers are depicted on screen.

By Andrew Lowry

A modern noir that nods perfunctorily at the genre’s conventions, but sidelines them as quickly as it can to get to its real business.