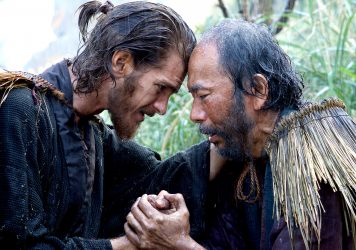

Martin Scorsese’s Silence is a film that was nearly 30 years in the making. In that time, a plethora of articles and editorial investigations looked at the director’s own faith and how, through the moving image, he was able to personally grapple with the abstract concept of divinity.

Various interviews with Scorsese across the decades saw the director waxing nostalgic about his Italian-American Catholic upbringing, his plans to become a missionary, and later, the feelings of doubt and a desire for religious clarity. Silence brought faith back into his sphere of consciousness, reawakening the sense that religion has always played a vital part in the director’s work, even the drug-hazed and bullet-studded gangster epics upon which he made his name.

Written explorations of the director’s faith have conveyed the message with gusto, picking out the spiritual symbolism of characters like Travis Bickle in 1976’s Taxi Driver, with his saint-like agenda to purge his troubled mind, or highlighting 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ as an example of Scorsese’s obsession with religious doubt.

A beautiful new video essay by freelance editor Jorge Luengo Ruiz offers a beautiful visual summary of the supposed watchful eye of God that permeates the Martin Scorsese’s work. The piece, entitled ‘Martin Scorsese: God’s Point of View’, is an exemplary bolt of cinephile analysis that capitalises on the power and potential of the essay form as a format for broader discussion and focus on visual specifics. Ruiz uses clips from 24 Scorsese features as a way to showcase his frequent use of the bird’s eye – or God’s eye – shots, the way he (and editor Thelma Schoonmaker) beat-match the footage to the soundtrack, as with Max Richter’s ‘On the Nature of Daylight’ in Shutter Island.

The video engages in a way that a written examination of Scorsese’s style cannot necessarily achieve, prioritising image over words to depict a certain hovering presence that’s hard to amply describe. It presents a range of scenes and characters, from Bill the Butcher sharpening knives in 19th century crime drama Gangs of New York to Jake La Motta in the ring in boxing classic Raging Bull, with each one shot from above, like or a moral voice, to look down on.

In the description Ruiz lists his sources and asks a single question: is God watching in all of Scorsese’s films? The question is not an overtly clickbait attempt at being controversial or revolutionary – there is no suggestion of an absolute final answer, but merely an astute awareness of a recurring metaphorical motif. Paying attention to these small features is an interesting and unique mode of admiration and encourages active, thoughtful audience participation.

Ruiz does not narrate the video. Instead, he allows the images to speak for themselves. This proves to be the most enjoyable aspect of his creation. Harun Farocki, the late German filmmaker and pioneer of non-narrative essays, saw his own work as, “images commenting on images” and this is exactly what Ruiz has achieved here. Too often the makers of visual essays narrate over the material they are examining, offering a subjective reading of the material rather than something which is open to the poetry of interpretation.

By allowing the images to breath on their own, this video leaves room for personal contemplation is left open. ‘Is God watching?’ remains just a question, a way of inviting thoughts on why Scorsese is so fond of that particular, top-down camera angle. Whether it’s intentionally suggestive of something holy or simply an cosmetic choice remains up for debate, but as a companion piece to Scorsese’s own feature work, it provides new ways of looking at cinema. It inspires others to start noticing intriguing idiosyncrasies.

Published 5 Jan 2017

By Paul Risker

Silence isn’t the first occasion when the director’s obsession with religion has been at the fore.

Scorsese’s monolithic passion project finally arrives, and it’s a ripped straight from his spiritually devout heart.

By Paul Risker

With Martin Scorsese’s seminal crime drama finally out on Blu-ray, we gauge the film’s enduring influence.