Graduate student Helen (Virginia Madsen) and her colleague Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons) are recording younger undergraduates tell macabre, can’t-really-be-true stories that happened to a friend of a friend, for a study on urban myths.

The first such myth that Helen (and we with her) hears in Candyman is the story of a young babysitter Claire who, on the point of giving her virginity away (and not to her boyfriend Michael, but to ‘bad boy’ Billy), says the forbidden name ‘Candyman’ five times in the mirror, and is slaughtered, along with the baby, by the summoned figure, with the hook that he has in place of his severed hand.

Typical of the pattern of urban myths, this Candyman story traffics in social taboos, as well as deep-seated ambiguities about its own veridicality – and as the student narrates her tale to Helen, it is also realised visually before our very eyes, so that it is made up of the same filmic material as everything else in Bernard Rose’s feature.

Here, the boundaries between myth and reality are fluid – and just as one might easily reconstrue the student’s transmitted story as crazy Billy’s self-justifying account of his own murderous crimes of passion, the rest of Candyman, and the story that it tells about Helen, is open to more than one interpretation, some rational, some supernatural.

Helen is under a lot of pressure, both personal and professional. Her older husband Trevor (Xander Berkeley) is a professor of English at the University of Illinois. And not only does he have a wandering eye, as Helen knows full well, for pretty young students, but he is also stealing the thunder of Helen’s thesis by himself giving a lecture series on urban myths (“the unselfconscious reflection”, as he puts it, “of the fears of urban society”).

So when Helen hears from university cleaners about a grotesque murder attributed to Candyman over in the projects of graffitied and gang-ruled Cabrini Green, she rushes in, despite warnings about the dangers, to investigate what might be the breakthrough that she so needs to prove herself in the men’s club of academia. “We’ve got a real shot here,” she tells Bernadette. “An entire community starts attributing the daily horrors of their lives to a mythical figure.”

At Cabrini Green, mother Anne-Marie McCoy (Vanessa Williams) and young boy Jake (DeJuan Guy) both confirm that a hook-wielding ‘Candyman’ is conducting a reign of terror, and comes “through the walls”. There is, it turns out, a perfectly rational explanation available for all this. Meanwhile Helen’s curiosity and imagination are whetted when she hears from Trevor’s colleague Philip Purcell (Michael Culkin) that, according to legend, Candyman was the portrait-painting son of a slave, horrifically lynched (mutilated, bee-stung and incinerated) in 19th century Cabrini Green for his love affair with the white daughter of an employer.

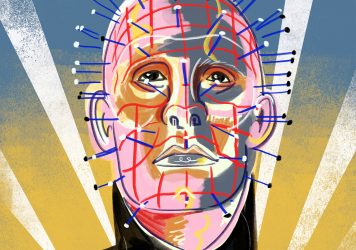

As Helen, a white, middle-class woman herself, crosses the threshold of her own city’s African-American underclass, she is confronted with a history of abject impoverishment and marginalisation that she has (literally, given her elevated condo) overlooked. Helen fills the unbridgeable gulf between Cabrini Green and her own life with myth and madness, calling upon Candyman (Tony Todd) at the mirror and finding a place in his immortal legend for herself.

Candyman is adapted from the short story ‘The Forbidden’ by Clive Barker, but in relocating its events from Liverpool to the Chicago projects, Rose is able to make his screenplay twist and turn along the neighbourhood boundaries of sex, class and race, in a sociopolitical story flexible enough – with a bit of imagination – to accommodate anyone.

Permeated with Philip Glass’ funereal-minimalist score, and punctuated by ‘god’s-eye’ aerial shots that offer the only semblance of objective perspective in an otherwise subjectivised film, Candyman offers a plot riddled with narrative ambiguities that are never fully resolved, all as a spur to the hooked viewer to spread their own take on the Candyman myth, and so to keep it alive.

Candyman is released by Arrow Video on Blu-ray, in a brand new 2K restoration from a new 4k scan of the original negative, supervised and approved by writer-director Bernard Rose and director of photography Anthony B Richmond), on 29 October.

Published 28 Oct 2018

With a pinch of Hammer Horror and a dollop of ’80s gore, this meta horror is the boldest in the series.

We pay homage to director Clive Barker’s majestic suburban gore aria from 1987.

It may not be the most iconic piece of film music, but Tobe Hooper’s organic, visceral soundtrack is uniquely unsettling.