Madness, adolescence and nostalgia colour Gregg Araki's poetic mystery starring Shailene Woodley.

In a nostalgia driven coming-of-age tale that drips with all the suburban portent of a Gregory Crewdson photograph, Kat (Shailene Woodley) narrates the events surrounding the disappearance of her unbalanced mother, Eve (Eva Green).

Based on the novel by American fiction writer Laura Kasischke, White Bird in a Blizzard is a poetic mystery, deeply entrenched in an ’80s aesthetic, boasting a sonorous soundtrack by the Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie and superlative cinematography which takes its form in a series of simple suburban tableaux populated by boys-next-door, day-glo costumes and soulless shopping malls.

But if this sounds like typical Araki fare you’ll quickly find yourself far from the narratively unconventional and provocative queer dramas of yore. White Bird isn’t retreading the subcultural kaleidoscope of the Teen Apocalypse Trilogy, instead making new ground with a number of almost coy literary left hooks.

In one of many narrated epiphanies, Kat pithily states one of the film’s central contentions: “I felt like an actress, playing myself. A bad actress doing a shitty job.” All the characters in White Bird wrestle with their predestined roles, performing them adequately at times but never quite fulfilling them to theirs or anyone else’s satisfaction.

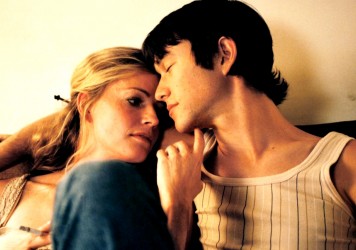

The acting is fine, but often pointedly off-kilter, as varying styles sit uncomfortably astride one another, with more straight-laced turns coming from Christopher Meloni (as Kat’s father) and Woodley, while Eva Green’s snarlingly overwrought execution evokes Joan Crawford-esque Old Hollywood grande dames. Eve is a lurching, unhappy, embittered drunkard, pining for lost youth. For her, the elaborately staged Americana quickly became bloodless and entrapping. Domesticity is empty, repetitive and loveless.

Even in Eve’s absence, White Bird harks back to film and literature’s foreboding first wives and disappeared women. A cameo by Sheryl Lee (Twin Peaks’ Laura Palmer) feels apposite, but even sans this obvious cultural hat-tip, Eve’s legacy looms large in the Connor household like The First Mrs de Winter in Daphne Du Maurier’s ‘Rebecca’ or Antoinetta Mason, the original ‘madwoman in the attic’ from ‘Jane Eyre’. Dialogue and scenes continuously allude and drop clues to this: “sometimes I thought… she was going to burn the house down.” But Eve doesn’t get to dance on the fiery balustrades of Thornton Hall, she merely disappears.

Standing on the threshold of adulthood, beyond increasingly impulsive actions and a growing nihilistic streak, Kat seems outwardly untouched by her mother’s unexplained disappearance. She wants to know where she’s gone, but not to the extent that it’s going to alter her social and sexual priorities. But beneath the adolescent insouciance, she’s plagued by haunting dreams where she searches for Eve in a snowstorm. Her therapist dismisses them – “sometimes dreams are just dreams.” But in director Gregg Araki’s world, dreams are never just that, and as the title suggests, viewers will instead have to search hard for hidden clues.

Published 5 Mar 2015

An intriguing cast, a compelling premise.

Madwomen in the attic.

An absorbing portrait of a woman, Gregg Araki continues to play exquisite corpse with film form.

Shailene Woodley appears bemused and bored by this crushingly lacklustre science fiction franchise.

The mischievous indie auteur talks about the importance of shoegaze music to his new film, White Bird in a Blizzard.

Gregg Araki has abandoned his rough-around-the-edges exploitation style in favour of the dream-like textures of David Lynch.