The moral minefield of Carol Reed’s The Third Man insures its place in the pantheon of greats.

If you’re engaging in a discussion about the greatest films produced on these fair isles and The Third Man goes unmentioned for more than… two minutes, then sorry, but you’re doing it all wrong. Pristinely restored and re-released in the UK, Carol Reed’s crepuscular 1949 masterwork only matures with age, its themes becoming more fragile and illusive the closer we get to it. Like Orson Welles’ own Touch of Evil, to come in 1958, this is a film which does away with such cretinous inanity as offering up goodies and baddies, instead presenting its cast of characters as doing things which they believe to be good, but are not seen as such through the eyes of observers.

The politically temperamental setting of post-war Vienna is vital to the story’s telling, a city partially levelled by its Soviet saviours in a bid to drive out Nazi occupiers, but a city that’s mid-restoration and open to those chancers wanting to take advantage of a system of emergency bureaucracy. Harry Lime (Welles) took such a chance, and paid dearly for it, now stiff in a box and six feet under. His old pal Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton), a dimestore novelist and yank ex-pat, can’t quite fathom how this could happen to such a slick operator, a man who has historically danced through the raindrops, and in far more testing times. No longer able to accept the job that Harry had promised him upon arrival (but of which no actual details were revealed), Holly has nothing else to do but relent to his primal detective instincts and find out if there has been any foul play in his old pal’s death.

Knowing that Orson Welles stars in the film and is unlikely to be playing a character who dies prior to the film’s timeline, Reed teases and teases by constantly assuring that Lime is dead, making Holly (and, by extension, the audience) more intrigued in how this character will end up making a grand appearance. In the eyes of the law, Harry is a bad person who deserves to be dead. Yet, as we discover, he was perhaps not a man of outward malice, even though he didn’t opt to carry out his dealings the most legitimate of ways. The malevolence in The Third Man is capitalism, which is ironic given that the territory has been commandeered by US allies. The nature of Lime’s crime is a question of basic morality which is muddied to near-total obscurity by time and by place.

Harry Lime intones a famous monologue from atop Vienna’s still-operational Wiener Ferris Wheel where he compares the people down on the ground to insignificant ants. It’s a powerful image, reflective of a callous attitude that’s almost a necessity if you want to enter into a profession where what you do has an effect on a wide, unseen swathe of society. When the bombs fell on Vienna, those they fell on where mere ants, haplessly crawling as they met with their doom, sent to them by men who were only trying to help.

Published 25 Jun 2015

Carol Reed’s noir classic has received a restorative spit-shine.

Becomes more deliciously complex with each new viewing.

One of the great British artworks of the 20th century.

Orson Welles is some kind of a man in this grisly, ultra-melancholic border-town noir from 1958.

By Ivan Radford

The director’s deep affection for his home city can be felt throughout his revered body of work.

By Adam Cook

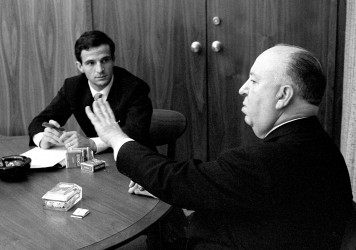

Two grand masters come head to head in this insightful documentary from film critic Kent Jones.