This drab Depression-era procedural takes a sideways look at the Bonnie and Clyde saga.

It says a great deal about The State of Things that a little over half a century after Bonnie and Clyde rekindled America’s love affair with two of its most infamous outlaws, while at the same time signalling the dawning of an exciting new era of auteur-driven cinema, we now have a distinctly straight-laced, unromantic Netflix film about the narcs who took them down.

Arthur Penn’s New Hollywood touchstone chronicled a pivotal moment in American history while creating one of its own. Conversely, the latest feature from The Blind Side and The Founder director John Lee Hancock feels wholly inconsequential both in terms of its narrative scope and broader cultural value. Where Penn broke all the rules, Hancock does things strictly by the book; somewhat ironically, given that his film pays homage to a pair of cops whose methods were anything but orthodox.

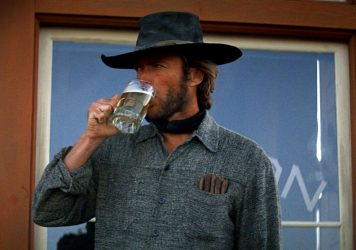

The Highwaymen sees Kevin Costner dust off his Stetson to play Frank Hamer, a respected former Texas Ranger who is brought out of retirement to apprehend Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow following the bloody Eastham Prison Farm breakout of 1934. He’s partnered by sometime associate Maney Gault (Woody Harrelson), who is similarly seasoned and rusty yet no less up for the fight. We follow Hamer and Gault as they doggedly pursue the perps across state lines, always seemingly one step behind but steadfast in their determination to serve justice one way or another.

Taking a sideways look at this familiar Depression-era fable, John Fusco’s screenplay attempts first and foremost to set the record straight on Hamer – not only the key role he played in Bonnie and Clyde’s demise but also his general conduct and character. Hamer has been given short shrift in popular culture, so it’s fair as well as accurate to depict him as canny and diligent, not the righteous, vengeful buffoon portrayed by Denver Pyle in 1976. (One year after its release, Hamer’s family sued the film’s producers for defamation, eventually settling out of court for a six-figure sum.)

But there’s something else going on here. The longer the film goes on (and on and on), the more intensely it scrutinises the “myth” of Bonnie and Clyde while simultaneously fluffing Hamer’s own legend. So when Kathy Bates’ Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson mentions Hamer in the same breath as Wyatt Earp, it’s not intended simply as a perfunctory nod to an earlier Costner cowboy picture – by aligning these two archetypal Western lawmen, the film is asking us to consider whether we’ve been worshipping the wrong heroes all along.

It’s an unconvincing plea, not least because in addition to hunting folkloric bank robbers, the real Hamer also combatted Mexicans and Native Americans over the course of his decorated career. This is not to denigrate Hamer or hard-working police officers like him, more to point out the hypocrisy of posthumously celebrating a white establishment figure whose story is inextricably bound up with that of the ruthless expansion of the American frontier during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When Fusco first pitched the idea for The Highwaymen back in 2005, he originally wanted Robert Redford and Paul Newman for the leads. Casting two icons of Hollywood’s last gilded age would certainly have elevated proceedings and provided a richer subtext – an inverted bookend to the very chapter in American (film) history it strives to rewrite. But on this evidence there’s little to suggest this was ever destined to be more than a drably conventional procedural. In the end, Fusco and Hancock fail to lift their subject beyond the footnotes of a saga that will forever be synonymous with the lovebird killers at its heart.

Published 26 Mar 2019

Wait, Bonnie and Clyde were the bad guys?!

Narc life!

An ultra-conservative and criminally dull exercise in selective revisionist history.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.

By Elena Lazic

Michael Keaton turns the humble hamburger into big business in this supersized American Dream satire.

This controversial 1973 western ranks among the director’s finest works.