Has Edgar Wright delivered the most satisfying movie in-joke of 2017? In one particularly nerve-wracking scene in Baby Driver, a single lens from Ansel Elgort’s sunglasses pops out amidst the panic. Through this oblique sight gag, Wright evokes the image of Warren Beatty as notorious bank-robber Clyde Barrow, losing a lens in his glasses mere moments before he and Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) meet their fate under police gunfire. But even Arthur Penn’s masterful 1967 crime thriller can’t take credit for this eyewear malfunction, with Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal debut feature from 1960, Breathless, granting doomed protagonist Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) the same minor pre-death indignity.

In extending this endearing pop culture daisy chain of royally screwed criminals, Wright has underscored a profound through-line of influence from the French New Wave to Bonnie and Clyde to some of the most brutal, daring or just downright enjoyable cinema that Hollywood has cranked out in the five decades since. Penn’s controversial picture was a bullet-riddled Ford V8 crashing through the doors of the mainstream, clearing the entrance for a new, more cynical age of cinematic sex and violence while studios and critics alike scrambled to keep up.

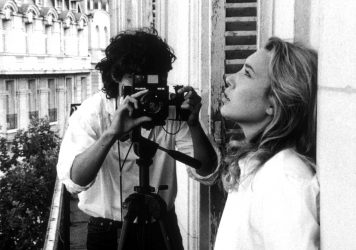

Like the murderous historical couple that held up banks, stores and gas stations across the American south in the 1930s, the script to Bonnie and Clyde did its fair share of travelling before stopping at its final destination. When writers David Newman and Robert Benton, a couple of French New Wave fanboys particularly fond of the tragicomedy of François Truffaut, initially sent their screenplay to Penn, the director turned the project down due to prior commitments. The pair then turned to Truffaut himself, who provided further input on the script but would also decline. Godard too was approached but it quickly became apparent that the legendary iconoclast couldn’t function within the big studio system.

Truffaut then hooked Newman and Benton up with actor-producer Beatty, who insisted that their very French screenplay needed an American director. Thus the script would eventually circle back to Penn with additional rewrites from a man soon to be recognised as one of the great scribes of the New Hollywood era, Robert Towne, whose credits include Chinatown and The Last Detail. What emerged from this cyclic journey was a crime thriller that channelled the fatalistic irony, jumpy rhythms, sharp tonal shifts and shrewd self-awareness of the New Wave into an exhilarating and profitable work of white-hot entertainment.

New Hollywood still being Hollywood, the project’s transition from the hands of Benton, Newman and Truffaut to Beatty, Penn and Towne necessitated a measure of compromise (the original script saw Bonnie and Clyde in a bisexual three-way with their getaway driver). Still, Godard and Truffaut’s existential blend of sex and death bleeds through vividly, only now enriched with an all-American proclivity for the operatic. You’ll see it in every flash of dread in a foolhardy killer’s eyes and every sensual caress of a loaded pistol. Hell, you’ll even find it in the blonde bangs that flop messily down over Bonnie’s glamorous visage.

It is, after all, the ugly-glamourous aura of stardom imbued in the film’s title characters that hit a nerve with so many of its detractors. Bonnie, Clyde and the rest of the Barrow Gang are living in a bubble of fame, adventure and perceived inconsequentiality that’s intruded upon by a grim, bloody reality.

Consider how the oblivious fugitive in Godard’s Breathless models his tough-guy image after the noirish persona of Humphrey Bogart. Now jump ahead to Bonnie’s merry rendition of ‘We’re in the Money’ after a screening of Gold Diggers of 1933, or her self-mythologising poem that offers a romanticised take on the couple’s life and impending death. The gun-toting Clyde may, ironically enough, be sexually impotent but the couple’s famed demise – a devastating slow motion climax that would forever raise the bar for cinematic violence – feels like the predetermined petite mort that would confirm their status as eternal lovers and icons of history and the screen.

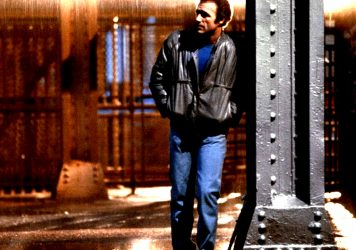

If the New Wave was a case of the French critics deconstructing the methods and iconography of American cinema in order to fashion something new and exciting, 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde was arguably the moment where these forward-thinking revisions truly found their way back to the States. Despite its obvious European predecessors, Penn’s rural tale of Depression-era carnage and courtship feels distinctly, passionately American, and its influence can be felt not just in the bold era of homegrown cinema that followed but also in more recent purveyors of artful savagery.

From Tarantino’s vicious post-modern gunplay to the tragic and self-conscious myth-making of Andrew Dominik’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the spirit of Bonnie and Clyde continues to leave a corpse-littered trail through American cinema. In Godard’s Breathless, it was famously the greatest ambition of esteemed director Parvulesco “to become immortal, and then die.” For the stylish antiheroes of Penn’s film, those two contradictory fates have proven to be one and the same.

Published 8 Jul 2017

Classic crime-thrillers to seek out – from Rififi to Thief, Dog Day Afternoon to Reservoir Dogs.

By Matt Thrift

The director has been producing casual masterpieces since 1964.

By Matt Thrift

How many of these pulse-quickening set pieces have you seen?