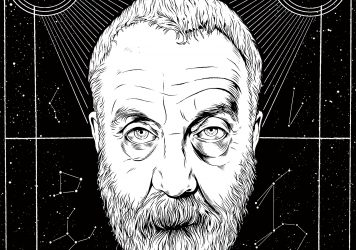

Veteran filmmaker Mike Leigh delivers a history lesson about the oft-forgotten 1819 Peterloo Massacre in Manchester.

With the UK government locked in a self-perpetuating, seemingly endless dispute over Brexit, it’s fitting that Mike Leigh has chosen another calamitous political saga as the subject of his latest feature. Part history lesson, part establishment satire, the stalwart writer/director’s follow-up to 2014’s Mr Turner sees him return to a region close to his heart – the northwest of England – in order to tell the story of a tragic and entirely avoidable clash that fundamentally changed Britain.

On 16 August, 1819, a peaceful pro-democracy rally was broken up by the Manchester Yeomanry, a local force of volunteer cavalrymen portrayed here as a booze-soaked mob. Dozens of innocent men, women and children lost their lives in the melee, brutally cut down by the Yeomans’ sabres and trampled by their horses, with hundreds more injured. Dubbed ‘The Peterloo Massacre’ by local journalist James Wroe, the incident caused widespread public outcry, boosting support for the nascent suffrage movement and leading to the foundation of the Guardian newspaper.

Many of the protestors had travelled to St Peter’s Field in Manchester from neighbouring towns and villages to hear the main speaker of the day, Henry Hunt, a self-styled man of the people who advocated radical action through non-violent means. Yet when Hunt (played with relish by Rory Kinnear) finally delivers his ill-fated address towards the end of the film, his words do not reach everyone. Leigh re-enacts the speech largely from the perspective of a family stood somewhere near the middle of the immense crowd, tantalisingly out of earshot – the implication being that it often takes more than conviction and a solid platform to get a message across. Especially when that message threatens to upset the status quo.

If Leigh ultimately ensures that Hunt’s point is made loud and clear by the time the closing credits roll, he does so without lionising the revered orator. In fact, he demystifies Hunt, revealing him to be a rather bland and boorish man. More grandiloquent than gallant, he saunters around in his trademark white top hat with the air of a man who deems himself above those whose interests he seeks to promote. Hunt is no hero.

Peterloo is no paean for the poor and perennially oppressed, no Dickensian postcard of social inequality, no romanticised vision of working class life. With strong assists from cinematographer Dick Pope, costumer designer Jacqueline Durran and production designer Suzie Davies (among others), Leigh takes us inside the cramped slums and cavernous factories, but crucially he never lingers on the squalid conditions in which the majority of people lived and worked.

Leigh’s intention is merely to highlight the significant contribution that ordinary labourers, homemakers and small business owners made (both in a community and wider economic sense) during the Industrial Revolution, as well as the impact they had in the development of our modern democratic system. Though it is always clear where the film’s sympathies lie, as a historical record Peterloo benefits greatly from Leigh’s even-handed, unsentimental approach. It may lack something of the emotional eloquence of Terence Davies, or the finger-jabbing indignation of Ken Loach, but the result is an acutely-observed survey of the class divide that existed in 19th century Britain.

Published 29 Oct 2018

Mike Leigh always means business.

A bit of a slog all told, but perhaps intentionally so.

An earnest, colourful portrait of liberty and tyranny in 19th century England.

LWLies sits for the British cinema icon who doesn’t mince his words to talk Mr Turner.

By Adam Scovell

Despite the widespread gentrification of east London, this quiet street appears much as it did in 1993.

The British actor reveals her personal connection to Mike Leigh’s historical epic.