London has never seemed so unforgiving a place as it does in Mike’s Leigh’s Naked. Presenting an odyssey through darkened streets of a seemingly never-ending nightmare, the film asks us with very little reassurance to follow the journey of two vile men through this city. The endless nights are broken only by a spattering of cold, lifeless mornings.

Naked shows the connections between violence, misogyny and misanthropy that manifest in different ways through the two men in question: working class and upper-middle class, northern and southern. Their divides are bridged by a series of abusive actions, filmed with uncomfortable relish on Leigh’s part. But London, and in particular the main house of its setting, do suggest some ways to read the nihilism on display.

Naked follows Johnny (played with an almost possessed mania by David Thewlis), a pessimistic wanderer who flees to London after assaulting a woman in Manchester. He makes his way to the house of Louise (Lesley Sharp), an ex also from the north who has settled into a mundane London life. Waiting outside her house, he meets Louise’s flatmate, Sophie (Katrin Cartlidge), who he sleeps with and begins to use to play mind games. Angry and abusive, Johnny wanders alone from the house into the night, meeting a cast of characters who seem to reaffirm his dead world view.

Running in parallel, we meet the equally abusive yuppie, Jeremy (Greg Cruttwell), who assaults several women before descending onto the main house which he is actually the landlord of. Whereas Johnny’s actions are born out of a dangerous frustration, Jeremy’s are born merely out of privilege and sadism.

The house at the centre of the film lies in Dalston, at the intersection of St Mark’s Rise and Downs Park Road. The area is described in the film as a “scrawny, unpretentious” – much to the irony of its current status as a postcard of gentrified east London, offering the usual variety of air-space coffee shops, vegan restaurants and avant-garde music venues. Yet upon visiting the house, the surrounding streets appear to have changed very little since Leigh filmed there.

The first image from the film that springs to mind when considering this house is of Sophie, the “wicky, wacky friend” who spends most of the film being physically and mentally abused by the two main leads. In the scene in question, Sophie has finally broken down and is leaving, carrying a small bag of possessions and a large, figurative ‘S’ as if she may possibly forget herself. She’s crying and staggers almost drunkenly down the curving steps of the house as her friends try very little to dissuade her from going.

The reason this scene sticks out so readily is because of how blasé her treatment is, by both the characters and the filmmaker. Even the women of the film, knowing what she has been through, and after briefly trying to remove her attacker from the house, still roll their eyes at Sophie; merely shrugging and wandering back up the stairs. Her departure is treated almost as comical but the road itself is really a hopeless place.

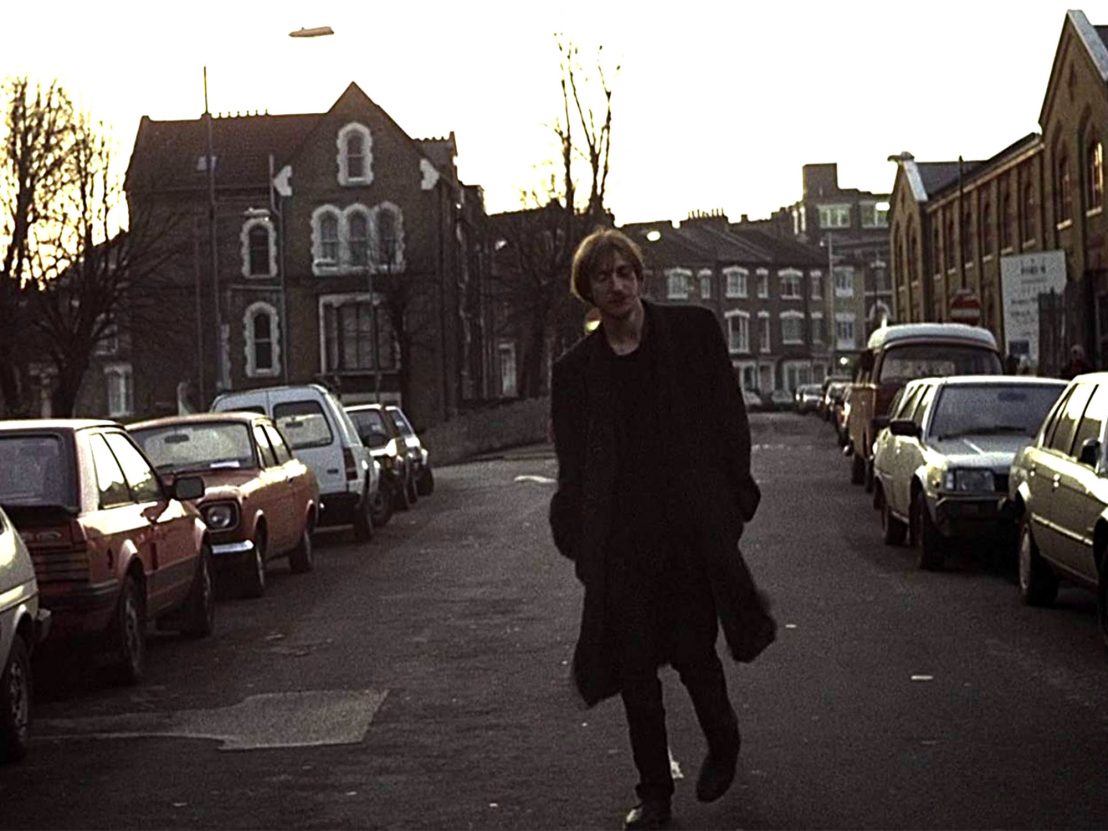

The house and the road come to the fore in Naked’s powerful final scene. After Johnny has had his wounds attended to, received from a beating by a group of thugs the previous evening, he is left on the couch after Louise has reconciled with him and gone to work. Johnny begins to chat up the main tenant, Sandra (Claire Skinner), once again falling into his routine of fatalism and the betrayal of all those around him, especially of himself. But, in what must be the first realisation of his own poisonous nature, he painfully dons his shoes, steals a wad of cash left by Jeremy, and hobbles out of the house. Leigh frames this moment beautifully in a single shot from the doorway, slowly following him down into the middle of the street where he meanders pathetically on to nowhere.

As the scene plays out, it’s apparent that it is the first time Johnny has really been honest with himself and is not performing his classical, end-of-the-world conspiracy monologue. It is also the first time that he seems to understand the destructive elements of his own personality, or perhaps his futile view of the world has simply been confirmed. Either way, whereas he fled the situation he caused in Manchester simply for self-preservation, here his behaviour seems to have progressed, even if only marginally. Johnny knows that he’ll continue to hurt everyone around him if he stays, just as in the previous few days. The trees are barren and dead in Leigh’s shot, having clearly been filmed on an empty winter’s day. The light has a strange, hazy quality as if it’s partly seen from Johnny’s still-dazed perspective. A Polaroid is the perfect format for recapturing this moment even though the trees were still green on my visit.

Considering St Mark’s Rise again, the structure of the road oddly mimics the character arc of the film. Even with their difference of privilege, the abusive nature of the two characters comes from the same masculine place. Just as Downs Park Road is split by the house into St Mark’s Rise heading north and south, Johnny and Jeremy tail off in different directions, especially as the former relishes the idea of dying young and causing destruction for pleasure.

He has no redemption though equally he has no consequences either. Ultimately they were part of the same byway, even if one had the realisation of his own vile character literally beaten into him. When Johnny hobbles into oblivion on Downs Park Road, he’s really doing everyone around him a favour, taking another route alone. It’s as honest a moment as you’ll find in Leigh’s brutal vision of the capital.

Published 7 Oct 2018

By Adam Scovell

Visiting the southeast London estate featured in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film makes for a dystopian experience.

The British actor casts a gaunt, morbid, uncompromisingly human figure in Mike Leigh’s nocturnal London odyssey.

By Tom Williams

Lynne Ramsay’s masterful second feature from 2002 offers a visceral depiction of grief and longing.