One of cinema’s Old Masters returns with this poetic and profound dissection of art and storytelling.

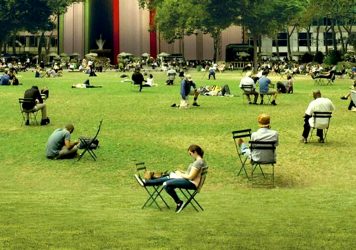

The same shot pattern recurs, like a refrain, throughout the nearly three hours of Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery. It’s a simple shot-reverse shot, beginning with a museumgoer in close-up, eyes directed offscreen, followed by a cut to a frame-filling close-up of a painting, and a cut back to a different viewer – and on it goes.

Like an early, playful experiment with continuity editing, the cuts stitch together observer and purported observee, and the loop stays open as Wiseman hopscotches back and forth from Italian Renaissance scenes and Hans Holbein’s court paintings, to students with sketchbooks and seniors with audio guides. It’s a democratic array of faces leaning in closer, shifting their weight, smiling knowingly, whispering kissily in their companion’s ear – a potentially inexhaustible recombination of contemplator and contemplated.

For his 41st feature film, the documentary godhead has bent his observational, open-ended style to an especially well-suited subject. As always, there is no onscreen identifying text, no talking heads or voiceovers, just vérité-style footage filmed by a small crew: What He Sees Is What You Get. But what Wiseman sees, in this case, is many people who are differently, effusively adept at interacting with art. It’s a pleasure to listen to the museum’s docents tailor their spiels – historical scene-setting for adult tours, analogies to other arts for school groups, stories for kids, with detail provided in illustrative cutaways.

“He is unlike his colleagues in that he does show all strata of society,” the leader of an art appreciation workshop for the blind says of Pissarro, just before a cut – hardly the only time Wiseman emphasises a comment equally applicable to his own cinema. Though viewers acclimated to direct-address in documentaries may find his style initially disorienting, Wiseman, in his role as editor, asserts his authorship of the footage he accumulates. From a budget meeting in which museum administrators discuss tightened spending limits and staff redundancies, we get a smash cut to a lecturer presenting a slide of one of Turner’s Carthage paintings: ‘Here is The Decline of the Empire’.

A major focus throughout Wiseman’s career has been the everyday interactions on which social institutions run, and given the unadorned purity of his raw material, there is an acute duality in his films which are both specific interventions into contemporary debates and near-abstract studies. So museum director Nicholas Penny’s scholarly, slightly pained presence in marketing strategy sessions speaks to the pragmatics barely behind the curtain at any large cultural organisation, in a way that’s of a piece with the oeuvre of the American director of High School, Hospital, Zoo, et al.

But this is also surely a more direct engagement with the politics of arts funding and the role of public and private money in Cameron’s Britain; the scene of Penny personally conducting a private tour of his prized acquisition, ‘Diana and Actaeon,’ for a donor may provide some insight into his decision to step down, announced the month after National Gallery’s Cannes premiere.

But while this is important to acknowledge, it’s obvious that Wiseman’s films, with their monolithic titles, are built to outlast any specific resonance – though this is true of National Gallery in a different way than of 1969’s Law and Order, say, with its axiomatic urban beat cops. When art restorer Larry Keith talks engrossingly about varnishes, degrading materials and ambiguous intention, it’s possible to forget, for several minutes at a time, that the object in the corner of the frame, over which he brushes his fingers so casually, is Velázquez’s ‘Christ in the House of Martha and Mary.’ The canvas isn’t peripheral – we are. As Keith goes on to say, a principal guiding his life’s work is that anything he does, future generations should be able to reverse in 15 minutes if it turns out they know better than we did how the painting should be preserved.

Increasingly in Wiseman’s arrangement of the material, docents are heard to remark on a painting’s mystery or changeability, and indeed the grand diversity of perspective in National Gallery – all those people, all those gazes – becomes a commentary on art’s infinitude. The film’s final minutes spiral outward into wings of the museum previously barely glimpsed, detouring to take in poetry and dance performances inspired by paintings we’ve already examined from multiple angles, before ending in a sequence of portraits, culminating with Rembrandt’s ‘Self Portrait at the Age of 63’, the Old Master returning our gaze and involving artist, artwork and audience in a discourse spanning five centuries, and surely beyond.

Published 9 Jan 2015

No Wiseman film is less than fascinating, but will art appreciation be a waste of his talents?

Three hours is hardly a long time to spend in the presence of great art.

Wiseman shows us the “how” of art appreciation, from politics to philosophy, in a film vast in scope, and richly suggestive in insight.

By Jordan Cronk

Federick Wiseman brings his insightful and layered filmmaking to one of America’s most liberal institutions.

Some of the world’s leading documentarians take the pulse of an ever-changing artistic medium.

Frederick Wiseman delves deep into one of New York City’s most beloved public institutions.