Intense melancholy and blissful romance mask an undercurrent of political outrage in Barry Jenkins’ rhapsodic take on James Baldwin.

Misty eyed and enveloped in the soulful cover of ‘My Country Tis of Thee’ that plays over the end credits of If Beale Street Could Talk, I was swept up into a vision. I imagined Jimmy in St Paul de Vence at his typewriter, knowing that no amount of distance can quell the calls from home.

And so he wrote and wrote, connecting himself to the smells and sounds of the Harlem in which he had come of age. I happened to be miles away from the City myself, also in France, missing my family. Much in the way writing ‘If Beale Street Could Talk’ became a portal to home for James Baldwin, watching this new film version became a portal to home for me. Upon seeing the crease of concern in Sharon’s eyebrows, I saw my own mother’s face. The face of a woman who knows her baby better than she knows herself. A matriarch tasked with holding it all together. I saw the sounds of my own community, felt the warmth of my own home, and felt thankful.

If Beale Street Could Talk recounts the trials and tribulations of a young couple in love, Tish Rivers (KiKi Layne) and Fonny Hunt (Stephan James) and their surrounding families as they seek to prove Fonny’s innocence after he’s falsely accused of rape. There’s overlap in the biographical details of both Tish and I, who feels like a version of my Nana in her youth, myself a version of her. Seeing her father, Joseph Rivers (Colman Domingo), in his work uniform, made me think of my own – both blue collar men who provide for their families by bending and lifting, clocking in, clocking out.

The embrace and slow dance in the living room between Joseph and Sharon (Regina King) is a christening of some sort, showcasing the intimacy and love that flows through their household. Suddenly I felt I had taken for granted all those finger snapping two steps I saw my parents share. I laughed to myself when they break out the good liquor, Hennessy, to celebrate Tish’s good news.

When films like If Beale Street Could Talk are released there is always the question of universality. People clamour to remind us that the specific can be universal, that we’ve all loved or have family, but I wonder if that consideration is even productive. Does it have to be universal? Props, gestures and language allow Jenkins to signify to a Black American audience, the residents of our own Beale Streets the world over. For ‘The Good Times’ by Al Green soundtracking familial conflict, or the references to playing numbers (dollar straight, dollar box!).

In an integral scene, Fonny and a childhood friend, Daniel (Brian Tyree Henry), chop it up over Newports, the cigarette of choice of the Daniel’s in my community who keep one tucked behind their ear, loitering the block in search of conversation and cheap beer. And, like Daniel, they’ve been beaten up by life, recovering from a bid or purely down on their luck but living and breathing, which counts for something. “This country do not like niggas!” Fonny remarks. Who he telling? This authenticity places Jenkins’ work squarely in a Black artmaking tradition rooted in the For Us, By Us ethos that’s existed since our cultural production first began.

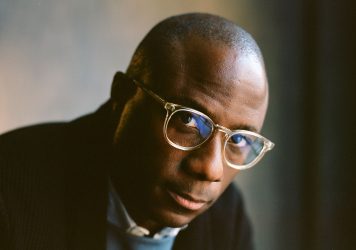

It drove home for me the importance of having a Black American director adapt Baldwin’s work (the first film adaption of his in English). What Jenkins has crafted isn’t lacking in beauty. A lush colour palette, close-ups that reveal the interiority of the characters and sweeping strings that swell over displays of affection are all part of what makes Beale Street so compelling, but more than that is the power of these storytellers converging. The film doesn’t linger too much in the tragic aspects of the story. Which would probably be a challenge for a less adept screenwriter.

It called to mind the latter half of Nikki Giovanni’s (an interlocutor of Baldwin’s) poem ‘Nikki-Rosa’: “and I really hope no white person ever has cause / to write about me / because they never understand / Black love is Black wealth and they’ll / probably talk about my hard childhood / and never understand that / all the while I was quite happy.” Something that could easily come spilling out of Alonzo Jr’s (the son of Tish and Fonny) mouth when asked to recall his own childhood in some distant future. So much of life as a Black person in America is pushing up against the forces that seek to render us invisible or dead. Depicting the nuance of that experience, not just the pain but also the joy, brings forth the honesty and complexity that I find myself in search of in the art that seeks to represent me and mine.

In the age of autoplays on footage of extrajudicial killings, not showing physical violence being inflicted upon Fonny is a welcome choice. The use of still images throughout serves as a reminder that this story isn’t purely fiction. Fonny looks straight at the camera: “Do you know what’s happening to me? In here?!” The bruises on his face and his bloodshot eye answer half of that question, leaving the viewer to use their imagination to conjure up the rest.

In this way, the film indicts you and I. If you genuinely haven’t a clue, then you’ve been in the dark about the world in which we live and how the prison industrial complex thrives on the pain of folks like Fonny. However, for anyone else, we empathise. We know what’s happening to him in there and what are we to do about it?

As the story unfolds, we watch as everyone involved attempts to do something. Mr Rivers and Mr Hunt join forces the best way they know how: to hustle their way into more money ahead of Fonny’s trial. Tish’s sister Ernestine (Teyonah Parris) stays on top of the lawyer and bookkeeping while Sharon takes a sojourn to Puerto Rico, hoping to come back to America with the truth to set them all free. Tish is trying to keep her mind, body and spirit healthy as she goes through her pregnancy, while also trying to hold her man down. We only ever see her going up to visit him. It becomes her job to relay news about him to the family.

There’s a scene in the Bank Street basement apartment in which Tish and Fonny have made their home. Daniel has joined them for dinner. After saying grace, the three break bread and the sounds of Nina Simone’s ‘That’s All I Ask’ echo the sentiments of Tish’s love: “I wouldn’t ask you to hold back the light of dawn, baby / that’s too much to ask to anyone / All that I ask is your loving ways / And I’ll keep you happy for the rest of your natural born days, baby.” The music heightens, loving glances and laughter exchanged. It suddenly dawns on me that Tish is asking for so little. She has her department store job, and her family, and her baby on the way, and all she wants is her man to complete the life that she’s building. And even that seems unattainable.

I’ve come to realise that this story is about more than love, as love is inevitable. Ms Hunt loves her son in the only way she knows how, through the gospel. Frank doesn’t love anyone in the world more than he loves Fonny, for he tells us so. Ernestine, Joseph and Sharon all wrap their arms around Tish in several scenes; a gesture of both love and protection. And we already know Tish and Fonny are a unit; soulmates. What a wonderful thing love is. It’s what keeps us buoyant while we helplessly watch our family, friends and lovers attempt to stay afloat under the weight of an oppressive system.

The tears I cried weren’t because I was in awe at the fact that the tenderness and warmth shared by the two transcends the glass dividing them, but rather that there is a barrier there in the first place. While love may be one thing, hope is something else entirely. Tish and Fonny’s boy is the embodiment of hope. The fact that Fonny never loses the light in his eyes speaks to the tradition of keeping the faith in the midst of such unfair circumstances, as one does to survive. To lose hope would be, in no uncertain terms, to die; literally and figuratively.

Published 5 Feb 2019

The Moonlight kid makes his big return with some Baldwin under his arm.

An astonishing and surprising follow-up to his award-garlanded marvel.

Jenkins has cemented his status as a very big deal.

The Moonlight director sits down to pick apart his wonderful James Baldwin adaptation, If Beale Street Could Talk.

For our first edition of 2019 we dive into Barry Jenkins’ extraordinary adaptation of James Baldwin.

By Josh Lee

By not showing physical intimacy, Barry Jenkins allows sexuality to surface in his film in other ways.