A Danish priest mounts an escapade to Iceland with a camera in hand and a dream of building a church in Hlynur Pálmason’s darkly comic epic.

When it comes to the International Feature Film category at the Academy Awards, the somewhat archaic submission process involves a country nominating just one feature from the year’s filmmaking output. Regarding eligibility criteria, international co-productions are in a tricky spot, whereby factors such as how much funding came from a specific country, or what per cent of the dialogue is in a certain language, determine which nation can most justifiably claim it as their own in the pursuit of an Oscar.

Awards season rumours suggest director Hlynur Pálmason’s darkly comic epic Godland fell victim to those eligibility debates. While some funding came from France and Sweden, the film was also backed by Icelandic and Danish production companies, is set mainly in Iceland after a Denmark-set prologue, and follows a Danish character’s attempted assimilation in Iceland. There’s a roughly even split between Icelandic and Danish dialogue, but in the end, neither territory submitted the film.

Godland may have been not Icelandic enough, but also not Danish enough. But then, this is a quite fitting outside-the-film circumstance for a story in which cultural clash and notions of societal belonging are explicitly part of the text; a film that includes separate title cards in both Icelandic and Danish at its open and close.

In the late 19th-century, Danish Lutheran priest Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove) is tasked with traveling to Iceland – then a remote Danish territory – to build a church at a Danish settlement. He brings a camera, intending to document the land and its people, and travels by boat with Icelandic labourers and a translator (Hilmar Guðjónsson), whom he befriends and is his only connection to the rest of the party.

When they arrive, their guide, Ragnar (star of Pálmason’s brilliant 2019 film, A White, White Day, Ingvar Sigurðsson), distrusts this Danish interloper, though Lucas is hardly the friendliest or most tolerant traveller himself. It’s Lucas’ own act of hubris that leads to the translator’s departure from the journey, and is partly responsible for his own injuries during the final approaches towards the settlement.

It’s no spoiler to say that the group eventually makes it to the destination of the future church, as it’s on the Danish settlement that much of the film takes place, and where rural conditions and conflicts in understanding only further exacerbate the priest’s crisis of faith and miscomprehension of reality. As the church’s construction slowly goes ahead, he finds potential connection with Danish-born local Anna (Vic Carmen Sonne), much to the disapproval of her father.

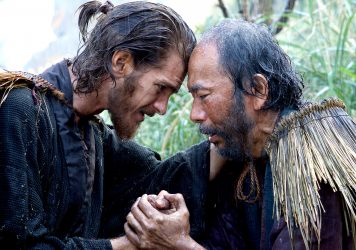

If that first hour or so is where the film resembles debilitating wilderness trek tales such as Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff or Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (in both content and quality), the claustrophobic second half is where valid comparisons to something like Shūsaku Endō’s Silence – though especially Martin Scorsese’s 2016 screen adaptation – come to the fore; where colonial arrogance and perceived enlightenment make for combustible mix ready to blow at the slightest provocation.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 4 Apr 2023

Every still for this film released since its Cannes launch is eye-catching.

There Will Be Mud. Much funnier than expected, amidst the harshness and tragedy.

Another elliptical and elemental treat from one of Europe’s great new filmmakers.

A police chief’s suspicion turns into an obsession in this chilly Icelandic drama from Hlynur Palmason.

Scorsese’s monolithic passion project finally arrives, and it’s a ripped straight from his spiritually devout heart.

Kelly Reichardt’s boldness in eschewing a sprawling retelling of how the West was won should be applauded.