Paul Walker’s swansong is a petrolhead poem to omnipotence and the concept of God in the digital age.

Much like Andrei Rublev, Andrei Takovsky’s transcendent spiritual epic from 1966, James Wan’s Fast & Furious 7 posts mankind on an interior quest for God, or at least an idle skirmish to feel the warm breath of some variety of divine entity. On this occasion, Man locates God, bumps chests, swings an industrial spanner in His general direction, and then enters into a game of muscle car chicken. Both parties walk away from the ensuing wreckage dazed and battered, but with no clear victor between them.

It may seem glib to be discussing the sublime indifference of some kind of all-seeing deity in the light of the untimely death of one of the F&F franchise’s banner stars – Paul Walker – but the film does pit itself as being about how God is a force that can be appropriated for good and for evil, exerting His will in ways which defy both the laws of physics and western logic in its totality.

Yet in this film, God is fallible, and this deduction serves to lend an immense power to a climactic coda in which Walker’s Brian O’Conner decides to take a leap into the void. Or, in this case, a sunny mountain sliproad to Arcadia. Fade to white. The legend, “For Paul”.

This may all read like highfalutin, mildly sacrilegious wibble, but it’s not. God does make an appearance in this film in a very literal sense, as a piece of computer spying software which allows “the right people” to turn lengthy manhunts into a mere formality. Via the secret (we presume) collusion between global business interests, every phone becomes a GPS beacon, every security camera a window onto otherwise protected privacy. It’s a tool by which nameless, back-room keepers of the peace (Kurt Russell) can track and trace to their heart’s content. It’s instantaneous, too, so no sitting around while the lab boys synch up satellite images or run numbers.

This software is called God’s Eye, and it places human beings into a position of all-seeing omnipotence. The film equates civil liberties and digital privacy with a higher power, suggesting that by not willingly relinquishing personal data for use by corporations and governments, we are in fact defaming the almighty in all his spectacular glory. The film refuses to have one of its characters speak up about the essential injustice of such a scheme and how it could easily be used for nefarious gains, like stealth marketing. Even Russell’s shady operative turns out as a straight-shooting good ol’ boy who would not even think that this software would be used for anything other than tracking down the Osama Bin Ladens of this world.

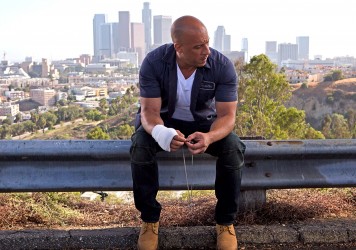

Dominic Toretto (Vin Diesel) wants hold of this funky gadget in order to track down madballs lone-gunner, Deckard Shaw (Jason Statham), whose very name evokes the inherent frailty of the human body and the melancholy, rain-lashed nightmare of existence. If Shaw himself isn’t God, then he may be the Devil, a constant and irksome presence in the team’s gymnastic vehicular sorties. Toretto wants to be able to find Shaw and take him down, but only on his own terms.

The characters of Fast & Furious 7 exist in a state of post-economic contentment, driven by a lust which can’t be quantified, where money never factors in to what they can do, how they can defend themselves, what they can drive and who they consort with. New sports cars appear at each global port of call, one for each member. The thrill of flying bullets fired from the modified luggage compartment of a tooled up variety coach driving at high speeds is a high octane form of pleasure which cannot be slapped with a finite price. In the end, there are no physical spoils, just honour, family, and all the high-end kit which seems to be passed on to them gratis between scenes.

These people are golden gods who walk between the raindrops of death. They are Biblical titans who stared into the abyss, the abyss stared back and ran off whimpering like a schoolboy with a gammy leg. Movies don’t have to exist in the real world. That’s what makes the movies. This feisty street racing make-weight turned carpark levelling juggernaut has gradually taken all leave of rational reality, to the point where in this seventh instalment, the action may as well be taking place in some kind of YA dystopia where clocks run on honey or teenagers have developed a way of procreating through touching wrists.

Some may question whether there are taste issues relating to the use of Paul Walker’s image in a gigantic, corporate money-making enterprise. But movies possess the power of resurrection, an embalmed memory for all time. He may not be with us now, but on screen, Walker doesn’t just exist — he lives. It’s fascinating and bitterly ironic that his swansong is a film which celebrates the astonishing durability of man to the point that death becomes an unthinkable annoyance.

Published 3 Apr 2015

Start your engines.

Defies all basic rationality to a near-Biblical degree.

Goodnight sweet prince…

By Lewis Bazley

The chase/stunt/joke formula is played to diminishing returns in the latest instalment of this 18-wheeler franchise.

By Jon Blyth

With the follow-up to Furious 7 now confirmed, where should the franchise go from here?

Dwayne Johnson ups the ante as the automotive action franchise successfully navigates a tricky existential crossroads.