‘Art would be useless if the world were perfect.’ This is the sentiment expressed by the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky in Donatella Baglivo’s 1983 documentary interview, A Poet in the Cinema. In it, he discusses subjects ranging from his childhood to the film market: “Art is born out of an ill-designed world. This is the issue in [Andrei] Rublev: the search for harmonic relationships among men, between art and life, between time and history.”

Set in the 15th century and depicting the life of the eponymous Russian icon painter, the film is less epic than episodic. Across eight distinct chapters, bookended by an epilogue and prologue, it imagines art borne of struggle and locates its protagonist in the violence and serenity of medieval Russia. Rublev, the man, is less the nucleus of the film than its axis – a point at which history hinges, and a prism through which time (present and perceived) is confronted as a force of human relationships.

Moving through ‘a sequence of detailed fragments’ in which Rublev is sometimes present, sometimes only an observer, the film works toward difficult questions: how is experience related, and how can it be communicated? How can art be true to its subject and its audience? How does, and how can a son learn from his father? How do you paint the trinity without just reducing it to the sum of its parts?

During the Cold War, ‘harmonic relationships’ were in short-supply. As such, it took some time for Andrei Rublev to be shown in its full form. Funded by Mosfilm, the preeminent Soviet film studio, and against the backdrop of a restrictive and officially atheist state, its retelling of Russian history, steeped in Christianity and spirituality, is striking. The film’s own production narrative is testimony to its serious attempts at reckoning with themes of how art is made – from how deep a life does it spring?

A version of the work was shown at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival, the year of Abbey Road and Samuel Beckett securing the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1971, a censored version of the film was released in the Soviet Union, and a further cut was later made for its release in the US. Its Tarkovsky-endorsed resting place lies at 3 hours and 6 minutes, from which, we are assured, only ‘overly long scenes which had no significance’ were removed.

Incidentally, Tarkovsky explained that the original idea for the film was not his. He had been walking in a wood outside Moscow with his co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky and their friend, the film actor Vasily Livanov, had expressed an interest in writing a script about the icon painter and suggested they do so together. Though this exact collaboration never came about, the script was nonetheless completed without Livanov (who had also wanted to play the lead) and was published in the Soviet film magazine Iskusstvo Kino, sparking discussion among historians, filmmakers and readers alike.

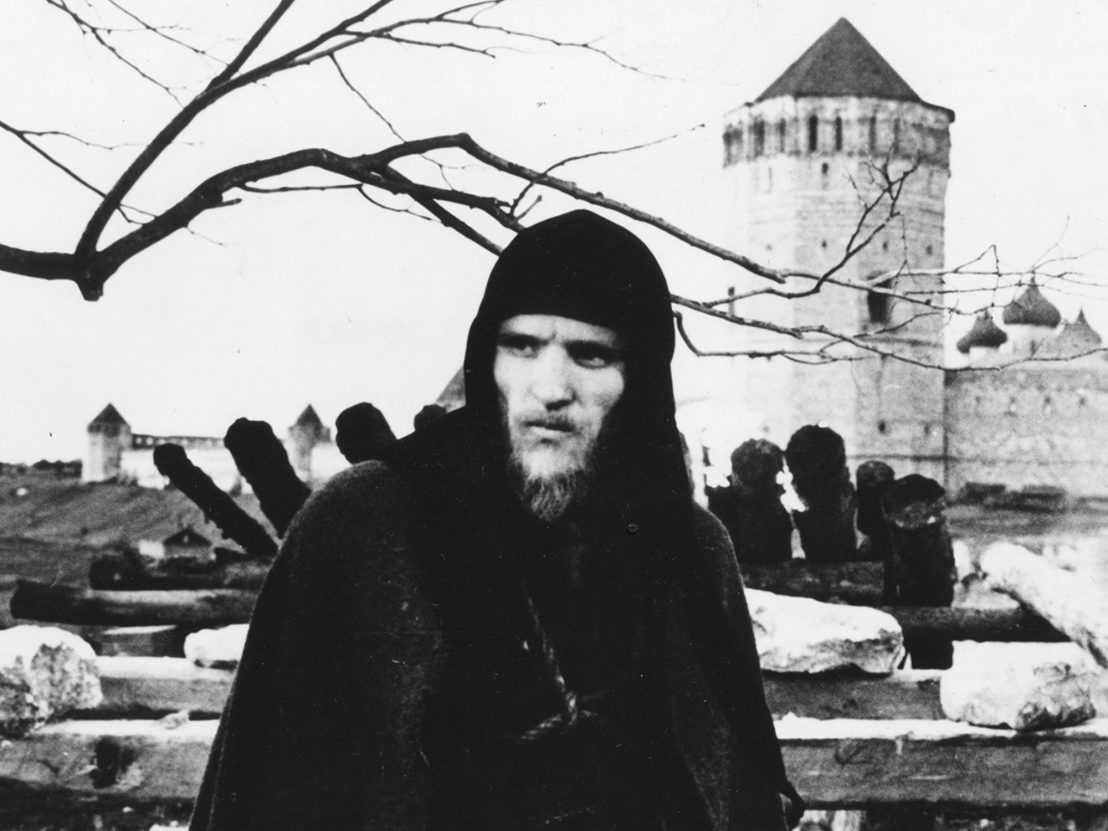

Tarkovsky chose Anatoly Solonitsyn for the title role because, in his words, besides his physical resemblance, the actor ‘had to be a man never before seen in film.’ Rublev and his work is of such significance in Russian history that a blank canvas was required for the audience to resist projecting expectations. Solonitsyn’s involvement marked the beginning of an important artistic relationship between the two men and Tarkovsky went on to cast him in all of his films, including the lead in his stage production of Hamlet in 1976. Solonitsyn and Tarkovsky both became ill due to exposure to toxic chemicals during filming on the location of Stalker in 1979, which, it has been said, was part of the reason for their both developing cancer, and their respective early deaths in 1982 and 1986.

Besides its depth and breadth of concern, Andrei Rublev is known for the diversity and extremity of its divergences. More than a historical biography or period drama, it is a collection of moments that can be encountered both in their own right and as figurations. Over the course of three hours, we actually meet more or less three semi-protagonists, most notably Rublev himself, but memorably, too, the young bellmaker, Boriska, whose “stingy” father has left him “without the secret” of his trade, but who nonetheless successfully manages to cast the bell, in the final episode. Through these various characters we are confronted with not History, but history in the lower-case: people shaping a passage through time, sometimes confounded, sometimes redeemed.

Perhaps most strikingly, acts of extreme violence are juxtaposed with scenes of haunting otherness. In the third episode ‘The Passion According to Andrei’ we witness a reenactment of Christ’s crucifixion, and in the fourth, ‘The Feast’, we watch a buzzing horde of naked bodies swarming through the woods with torches through to a lake. Andrei kills a man during ‘The Raid’, as he saves a woman from being raped, and a man is tortured by Tartars who pour a molten crucifix into his mouth and drag his body out of a church with horses. All this only for Andrei to then retreat from the world, taking a vow of silence and resolving to give up painting.

‘I think there exists a law: author cinema is made of poets and all great directors are poets.’ Andrei Rublev is an example, perhaps the most important, of Tarkovsky’s commitment to a formal ‘poetics’ of cinema. Its nonlinear narrative structure, the metaphorical interrelation of images, and its symbolism make for less a story about an event than a way of experiencing events interact. Bergman remarked that Tarkovsky was ‘the greatest’ because he ‘invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.’

More than this, though, what we sit through is not some abstraction of reality into reverie, but an attempt to think through this conflict: the cold fact of the world and our mediated experience of it. In the end, Rublev resolves to paint again. He comforts the bellmaker, Boriska, who is overwhelmed by the solitude of his achievement: ‘What a great joy for all men. You gave them such a great happiness: and you cry? Stop it!” Andrei Rublev is worthy of remembering not because it collapses life into art, but because it attempts to imagine how art can be life’s witness. Hence, Tarkovsky’s observation: ‘Art would be useless if the world were perfect, as man wouldn’t look for harmony but would simply live in it.’

Published 15 Nov 2016

The Russian director’s 1979 film is being reissued as part of a new retrospective.

Russian director Alexander Sokurov takes a dance with the music of time in this moving plea for saving art.

Ukrainian artist Feder Alexandrovich serves as a key witness to the untold story of the Chernobyl disaster.