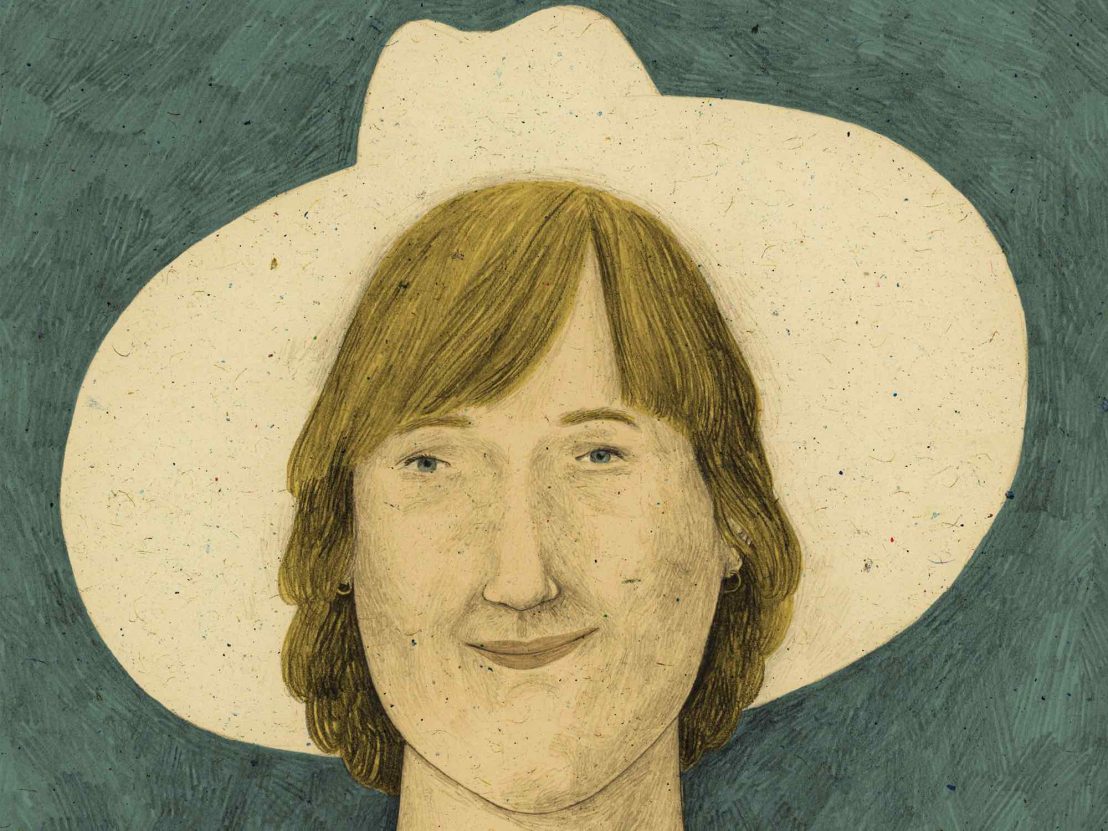

Western is a sensual, rustic drama which pays subtle homage to the classic horse opera, explains its German maker.

The wait for Valeska Grisebach’s third feature has been well worth it. The film is entirely unique and confident interpretation of what we might define as a classical movie western. She casts newcomer Meinhard Neumann as an enigmatic construction worker who heads to Bulgaria for a job, only to be trapped in the middle of a war of attrition between the brash ex-pats and suspicious locals.

LWLies: You made Longing in 2008 and there was this feeling of discovering a great new director. Then you went away for 10 years. What happened?

Grisebach: It was a mix of things: I had a child; I became a mother at 40 and I really wanted to spend some time with my daughter. The other reason is that I was teaching. I was giving advice for other projects. But also, to be honest, I really spent a long time thinking about this project. I think quite early on I decided that I wanted to do something on my fascination with the western genre. But then I was thinking and researching. It wasn’t so easy.

Do you enjoy the research stage?

I love research. I can do it for ages. For me it is the most beautiful part of filmmaking. In the end, it wasn’t easy to write. I wanted to have a narrative, but I also wanted to hide it. I wanted to make all these links and associations with other movies. And then we had to postpone for a year because there was some money missing. The life between the films is very nice. It’s a time to not think about film.

Is research for you sitting alone in a library, or going out on the streets and talking to people?

I read a lot of books. But for me it’s to go outside and confront an idea. I want to take a question and connect it with reality. In the beginning, I wanted to talk to people, mainly men, about their “western” moments in life. I went onto the street and was looking for men that I could imagine on a horse in a western. Very soon, I ended up moving towards construction workers. They have tools on their belt, and they wear work clothes and have this certain surly attitude. I asked them if I could invite them for a casting and an interview. It’s a beautiful moment, and a lot of people say, ‘Yes, why not!’ In this situation, these men were hesitant, but as soon as I said I wanted to make a western, they agreed.

When you said it was going to be a western, how did they react?

I told them it would be a contemporary western, and maybe only one that I knew secretly. It was a joke. I said that we wouldn’t be travelling back in time and there would be no need to act like a cowboy would act.

How early in the process did you know you wanted to give the film this elemental title?

For me, it was the title from the beginning. It was my working title. It was a sign. When the film was finished, I looked at it and thought it might have been too direct. In the end, I always come back to what I started with. It’s interesting that you have this little sign at the beginning that you can connect to.

When did your originally fall in love with the western?

I share this love with a whole generation. You associate this love with people in the States, or maybe in Italy. I was sitting in West Berlin, in front of the TV set, and watching a lot of westerns with my father. For me it was a very touching and exciting genre. Later I realised how much I felt attracted to that setting and those solitary male heroes. A friend of mine, who is also a director, told me that when she was a girl she identified with the male heroes of the westerns, but at the same time she was falling in love.

It’s a universal romantic seam of the westerns – searching for moments of freedom and independence. Or maybe the idea of coming home from life on the borders of society or in the wilderness. It’s a romantic seam, of people searching for a personal destiny. I became interested in the later westerns where they discuss this idea of constructing a modern society. The genre deals with ambivalence – the question of how much someone wants to be part of a society.

But also nationalism and colonialism.

Yes. Later on, when I was thinking about westerns, I realised I wanted to deal with this xenophobia. I live in Germany which has this special, terrible history. I did lots of interviews with people for research, and in families there’s another oral history which is different to the official German history. Sometimes you can hear things between the lines. In Germany, if you do something about nationalism or xenophobia, there is almost a genre for this. When I thought of this idea of German construction workers in another country, I could have both levels. They’re strangers who have to deal with desire and mistrust.

Was there a fantasy element to the film?

When I told Meinhardt about the role, I said that it’s like he’s in a Walt Disney world – a fantasy place where he can totally reinvent himself. He can take all these emotions from the people who live there. But there’s a moment where it breaks and they feel a bit of his weakness. It was clear that the film had to end at the moment he has to deal with his shame.

Western is released 13 April. Read the LWLies Recommends review.

Published 11 Apr 2018

A solitary protagonist searches for human connection in this vibrant drama from director Valeska Grisebach.

The German writer/director reveals how she quietly went about making one of the great films of the 21st century.

By David Hayles

Bone Tomahawk isn’t the first film to push the American frontier in a surprising new direction.