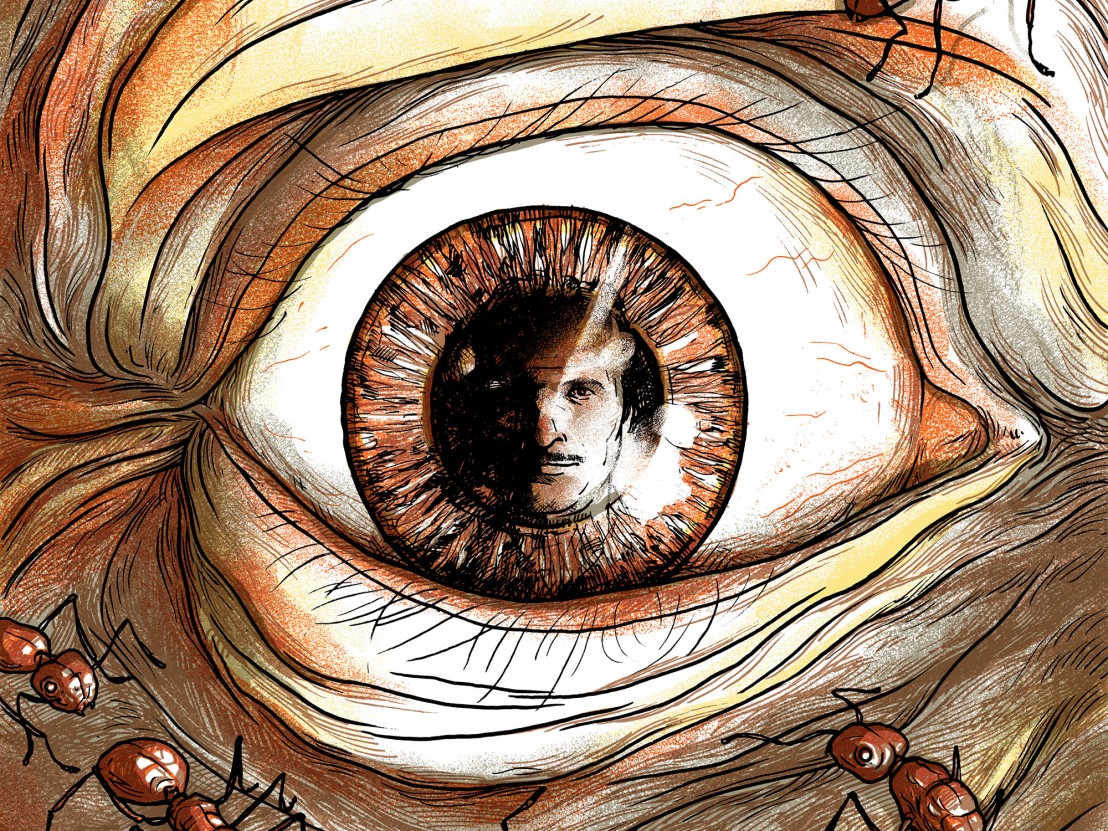

The Black Swan director reflects on the art of filmmaking, the trials of building a legacy and having a dark side.

To his fans, Darren Aronofsky is proof that you can make bold, independent, artistic films in an industry that disavows anything but the bottom line. To actors like Mickey Rourke – brought out of the wilderness for a lead role in The Wrestler – he’s a kind of spiritual healer. To aspiring filmmakers he’s a role model; the geek who rode a $20,000 debut all the way to the top table of Hollywood.

His films, five of them in the last 12 years and each its own peculiar struggle, have made Aronofsky one of the most talked about directors of his generation. And yet he’s one of those rare filmmakers whose work speaks for itself. Pi, Requiem for a Dream, The Fountain, The Wrestler and now Black Swan – all of them are linked by an abrasive energy and emotional pressure, by characters who are struggling to contain the demons within, by death as the road to awe. LWLies sat down with Aronofsky recently to chat Black Swan, Wolverine and Noah’s Ark.

LWLies: Can you tell us how you ended up making Black Swan after The Wrestler when at the time all the talk was about RoboCop and a Noah’s Ark project?

Aronofsky: It’s very hard to make movies so you’ve gotta throw a lot of things out there and see what sticks. I think my development is always a marathon with projects, you know? They all line up and they all get going and the ones that cross the finish line, often we’ve gone back to them many times to revisit a scene or a story or something about them that grabs our fancy and allows us to keep pushing that one closer to the finish line. So Black Swan’s been in development for eight or nine years and there was something about it that kept pulling me back to it. I don’t know what it was exactly. There were a lot of elements, for instance it was a chance to work with Natalie, it was the opportunity to make a werewolf movie, but it was a were-swan movie, the fact that it’s about transformation was exciting about it. There were so many different things that kept pulling me back. The challenge of shooting ballet and dance and making it sexy and fun and interesting. All those things.

Much of Black Swan is about the creation of art and the agony of creating art. Who do you identify with the most, is it Leroy (Vincent Cassel), who is the director who pushes and pushes for the creation, or is it Nina (Natalie Portman) who is the creator of the art itself?

I don’t know, I think I identify with all the characters. I think you have to as a director. That’s your job – to be able to put yourself into each character’s shoes, point shoes, whatever they may be wearing, and channel their emotion. It’s kinda like if you’re playing a chess game, you have to play both sides of the table honestly and truthfully and forget which side you’re on because each character needs to be played from a truthful and positive place. I’m clearly very interested in performance – my last two movies were about performance – and that’s probably because my biggest collaboration, or the one I enjoy the most, is with my actors. That work fascinates me – how they do it – so I think that’s me thinking about acting and actors.

Anton Corbijn said recently that he was going to make three films and then figure out what kind of filmmaker he was. Does that ring true to you – do you look back over five movies and think, ‘I never knew that this is who I was’?

Yeah, you know, I guess the only way I can comment on that is that just recently they did a Blu-ray version of Requiem for a Dream, and the studio was great, they went back to the original negative and re-canned it and then my team came in and updated the sound design and all that. You know, I didn’t really want to get involved but I watched the final product just to make sure it was fine and I could not recognise the young man who had made that film. I definitely couldn’t have made that film today; it was a different person who had made that. And so that was kind of interesting, how much you change. And to allow yourself to change is important, to allow yourself to grow. I think that’s what I’m trying to do is not hold on to past successes and past failures but to just live it and see what’s fascinating about the present and try to do something in the present.

It’s an important thing to be able to do. In your twenties the idea that as an older guy you might not recognise your younger self kind of fills you with scorn. You hate the idea of growing older. But to be able to look back and acknowledge that you’ve changed and be comfortable with it is an important thing.

Yeah I wasn’t necessarily looking down on myself I was just really curious who that person was. I couldn’t remember the mind-space of the person who had done that, so that’s what was interesting. And I think, you know, one of my mentors told me, ‘Never watch your films when you’re done’, and I’ve kinda subscribed to that. I’ll probably see Black Swan twice more and that’ll be it. I’ll see it on DVD when it comes out to make sure it’s okay, and I’ll probably see it once in the theatre when it first opens just to see what an audience, what a non-festival audience, reacts to. And that’ll be it. I think if you do stay connected to the films it can mess you up, you have to let them go and enter the world and disappear for a while.

Somebody who sat down and watched these five films of yours back to back might wonder if you were some kind of fatalist because almost all of them end either in death or the intimation of death or some sort of mutilation as a path to purity or whatever. What would you say to that?

I think there are connections between them even though the subject matters are radically all over the place. But I’m not a film theorist, I just make ’em as I feel ’em, and the characters I push to create just come out of me. So I haven’t really analysed what it’s all about. I’m not interested in that, I think it’s about the work and you just tell those stories.

You just try to be instinctive?

Absolutely. I mean, you know, it’s weird, for some reason I was attracted to Swan Lake but at the end of Swan Lake it’s a dual suicide; the prince and the white swan leap off a cliff. So I knew the film was going to end like that, it just was what it was. The Wrestler, there was no other way to deal with that – he was going off the top rope. That was the whole idea. So I don’t know if it’s purely because I’m driving the ship there or coincidence but clearly I’m attracted to these characters and stories. The characters I’m attracted to are not different from the characters you normally see in a film. They’re characters in extreme circumstances, under extreme pressures, either combating… in very challenging worlds and trying to find some form of peace or love or happiness.

“There’s all the pressures of not enough money, not enough time, what are we going to do, how do we fix this? It’s a real hustle.”

As you make more movies and you accumulate reputation, perhaps awards, maybe even wealth…

Wealth hasn’t come. The Wrestler, I got paid scale. Black Swan I did a little bit but I never get ownership. The problem is that all these films, no one on the planet ever wants to make them. It’s only me and my team that are pushing it forward, and we always have to find that one investor who either wants to break into the business or, you know, understands the vision and then they always pay an incredibly low amount of money and all the money ends up on the screen. So unfortunately that hasn’t happened.

Do you think that’s why people get so protective about you as a filmmaker, and get so vocal when you announce new projects – because they’re so aware that there is no one else like you and if you don’t make these great, kamikaze films that you’re making then we’re robbed of them because no one else will do it?

You’ve gotta tell that to the world so they give us money.

What is it that gets you out of bed on a cold, dark, early morning and gets you onto a film set? What keeps the fire burning?

Usually it’s character. There’s something about the character that I like and I want to explore and see. It’s also, you know, responsibility and duty. When you set up all this money and a team to do something, you do it. In a very British way, just getting things done. I have that instilled from my parents, but I think the thing that allows me to forget about the pain that is going to come while shooting a movie is the excitement of telling a story and exploring a character. And that’s it. You have to be in love with your characters and your story if you’re going to do these films because it’s just going to be that much harder, as you say, to get out of bed. And for some reason I always seem to shoot in the winter, which is a freakin’ nightmare. It’s just a nightmare. I’d love to shoot something in the Bahamas with bikinis at some point because it’d make my life much easier.

How does the pain of filmmaking manifest itself?

The pain of filmmaking – it’s really hard because it’s a grind. It’s long days, very intense days. I mean, they’re fun and you get to do a lot of great stuff but there’s just a lot of challenges and a lot of pressures and that’s just in the creative work. Then there’s all the pressures of not enough money, not enough time, what are we going to do, how do we fix this? It’s a real hustle.

Talking about genre, there’s the psychological side to Black Swan, but it’s a very physical film too. There’s a real old-fashioned horror film in there.

I don’t think we were fully conscious of it. We, you know, I don’t really make genre films very well – I’m definitely genre bending. If you think back to Pi, maybe sci-fi, I don’t know what it was. Requiem I guess is a drug movie if that’s a genre, but it was definitely surreal. I’d pay anyone if they could tell me what genre The Fountain was. The Wrestler I guess is a pretty straightforward drama to a certain extent. But once again Black Swan is… We knew we were playing with certain genres. We were into the old-school horror film, not what horror has become in today’s world. This idea that, we knew we were going to be doing these gags and we were excited by it. I mean, I was a little scared because they were just gags where you make the audience jump and scare the hell out of them. But I kind of took it as a challenge to figure out a way to do them in a fresh way and to surprise people and to scare them.

And then there’s some classic scares, like when the double’s knocked out and her eyes pop open. I mean, that’s just about as old and cheap a shot as you can get. But it works! It works on whatever 20 per cent of the audience and you can’t be fully inventive on all of them. We knew there were going to be mirror gags throughout the film because mirror gags, you cannot do a ballet film without the mirror because ballerinas are constantly staring at their line and their complexion and their body shape, and so we knew mirrors were a big part. And of course because of the doppelgänger elements, the reflection was going to be a big deal, but the mirror gag in horror films is the oldest gag in the world, you know? You open up the medicine cabinet and you put it back and – baaaam! – somebody’s there. So the challenge was, ‘How do we do some of those gags but not fall into the same old trap and do some interesting stuff?’ So, you know, we used a lot of digital effects to remove some of the reflections of the camera and crew so we could put the camera in impossible places and then we did a lot of one-way mirrors and a lot of really crazy, fun stuff. So we tried to push it.

Everything you said about yourself as a filmmaker seems to hit a brick wall in the shape of Wolverine 2, in that it’s a studio film, decent budget, comic-book genre movie. It took a lot of people by surprise. Someone said that even if you make the greatest Wolverine 2 movie there could possibly be, it still will look like a black mark on your legacy. What’s your take on that?

I have an interest in doing one of these films. I’ve been looking for one and I’ve been hunting for one. The reason being, I kinda want to make a film that other people want to make for once. I kinda just want to have that experience and, you know, I think it could be a lot of fun to check it out and have the support of the studio as opposed to fighting and fighting and fighting, and spending 14 months trying to make money and just go out and make a film. So I’m open to it. We’re looking for the right experience and we’ve been reading a lot of those to try to figure out which would be the one.

Do you feel in a way as though your audience is too precious about you? That they’re holding you to a higher standard? Why shouldn’t you go out and do this?

Exactly. The reality is, I just want to keep doing stuff that’s different and challenging and for myself, and me taking on a big Hollywood studio film would be a big challenge to try to deliver something like that which could work.

There’s still perhaps a feeling that if you were going to do that, there must be properties out there that show more promise than Wolverine.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, you know, we’ll see what happens. The reason I was interested is because of Hugh Jackman, who was a delight to work with, so that’s where we got to.

Do you have a dark side? A mirror image, evil you?

That can come out? I don’t know. I think, you know, within all of us we have the dark and light, and that’s why we can connect to characters that are all over the map and that have all different types of feeling and emotions. Fortunately or unfortunately what makes us people is that we’re complex creatures with the capacity for good and evil.

Published 24 Jan 2011

From Black Swan to High-Rise, the British composer reveals how he approaches making music for the movies.

If Black Swan is Darren Aronofsky’s claim to creative genius, it’s one that is undermined by the film’s own dual nature.