Ever wanted to start your own film festival? All you need is an empty space and a little community spirit.

“Come early”, a volunteer warned, “it’ll be busy.” Optimistic, I thought, for a screening of a little-known B-movie in the basement of a church on a Wednesday evening. I arrived 20 minutes early to St Giles Church in Camberwell. “I’m here for the film,” I told the man on the door. He looked concerned. “There might be some standing room available.” Down in the crypt, every possible vantage point appeared to have been taken, so I shuffled behind two pillars and sloped my shoulders, leaning into the man next to me.

Sarah, one of the programmers for Camberwell Free Film Festival (CFFF), climbed on stage to whoops from the crowd. She introduced the film, the 1962 fantasy-horror Carnival of Souls, with affection, wit and the preemptive flattery that it would only appeal to the discerning consumer of cult movies. The film played. We laughed at the abrupt dialogue, heckled the sexist characters, but for the most part maintained a respectful silence befitting a ghost story. The next night we did it all over again, this time with A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

On the walk home I passed a swimming pool, hair salons, an Islamic Centre, kebab shops, a Citizens Advice Bureaux, and imagined these neighbourhood institutions transformed into cinemas. This year alone, CFFF has screened films in pubs, libraries, churches, schools, bike shops, cafes and football clubs. So why not play Deep End in a swimming pool, Steel Magnolias in a salon, or Erin Brockovich in a law centre? This is the power of the Free Film Festivals: they transform space, making it temporarily public and, in the process, opening up the possibilities of urban communities.

The Free Film Festivals phenomenon started in Peckham and Nunhead, south-east London, in 2010. Founder Neil Johns, along with two friends, decided that monthly film clubs weren’t enough. They wanted to take films into schools, parks and housing associations, actively seeking out new audiences. No one planned for the idea to spread across the city, but soon New Cross and Deptford wanted their own screenings, and then Camberwell and Herne Hill.

Over the next five years, events sprung up across London under the Free Film Festivals banner. The organisation is, undoubtedly, gaining momentum. Attendance has risen year on year. There are five new festivals starting in 2016: Charlton and Woolwich, Blackhorse Road in Walthamstow, Streatham, Catford and Forest Hill. This year the Free Film Festivals format was exported to a university campus, SOAS, organised in part by Neil’s son. Everyone I’ve spoken to about the network is ambitious for its expansion. Neil talks about Free Film Festivals in remote islands of the West Coast of Scotland, and in small Midlands towns. The key challenge now is offering adequate support for anyone who wants to start their own festival.

The Festivals go some way to filling London’s hollowed out film landscape. South London’s cinemas in particular have suffered heavily since the 1980s. Victor, another chief CFFF programmer, gave me a potted history of the cinemas in Elephant and Castle, Camberwell and Lewisham, waxing nostalgic about the art deco architecture and late-night screenings. He concedes that the most important feature of the festival is its accessibility – the ‘Free’ part – at a time when cinema audiences are becoming increasingly resentful of high ticket prices.

Of course, low attendances are in part down to the explosion of digital viewing platforms. Online streaming and VOD services offer a more democratised, bespoke viewing experience. But right beside this exists the culture of piracy and illegal file sharing. There is an entire community of people who are used to paying nothing for films and working to make them widely available. The spirit of the digital commons is present in the public’s interaction with the Free Film Festivals, which strives to connect the shrinking of public spaces with a desire for a cultural commons. While young people understand this something for nothing, collective spirit, they’re also thirsty for a return to the cinema: watching movies remains, fundamentally, a communal experience.

Some of the festivals have a distinctly political feel. Deptford and New Cross, which kicks off next week, is returning to housing co-ops and community libraries, and showing films about austerity, inequality, climate change and the financial crash. Elsewhere, the programming is less obviously political. Victor argues that CFFF’s screening of Rocks in My Pockets addressed the long neglected issue of mental health. But most people I spoke to were keen to highlight the absence of any overarching political framework. One CFFF programmer, Hayat, said it was mostly a chance to go to the pub for a week. Neil agreed that the bottom line was that the process is fun for everyone involved. I met John at the opening night of CFFF, just before a screening of Good Vibrations. He’s an evangelical stalwart of the Free Film Festivals scene; he claimed, sincerely, that the organisation had changed his life, introducing him to important people in his life.

All of these accounts point towards the true political spirit of the festival, which transcends the films that are shown. The festival is a testament to the power of people to provide autonomously for themselves and their community. As the website attests, Free Film Festivals isn’t a charity, NGO, network, or company – it’s a ‘movement’.

The 1960s saw the emergence of film co-ops, which emphasised democratic programming and avant-garde experimentation. The Free Film Festivals clearly builds on this tradition with its emphasis on bottom-up organisation and the reclaiming of public space. But it draws on more populist traditions too. There’s something of the grindhouse about the events, a punkish disregard for comfort or aesthetic perfection. And there’s a deeper strain, too, one that runs from post-war years, when cinema attendance was at its highest and film culture was a cornerstone of working class social life. There’s that spirit of a cheap night out – pure recreation, nothing else, moments of luxury among life’s anxieties.

CFFF closed with a screening of 2015’s firebrand trans quest movie Tangerine in an LGBTQ-friendly pub. On the way to the bus stop I let my imagination roam again. I looked past the betting shops and quick loan companies, and saw the community churches, the pensioners associations and family restaurants. Only in my daydream state, these places had become hubs of activity – culture, discussion, friendship. The real achievement of Free Film Festivals is not to show movies, but to show us the places we live. Look up from the movies on our phones and we’ll discover that the world is a cinema – we just need to claim it.

The Camberwell Free Film Festival ran from 31 March to 10 April. The Deptford and New Cross Free Film Festival will run from 22 April to 1 May.

Information about all other Free Film Festival events, and how to set one up in your community, can be found at freefilmfestivals.org

Sam Thompson is editor of Whitey on the Moon

Published 13 Apr 2016

They may not be able to promise glitz and glamour, but small independent film festivals are now more vital than ever.

Themes of social displacement and isolation will be explored in the documentary series ‘Frames of Representation’.

By Sam Thompson

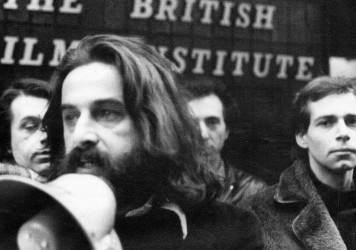

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.