Though light on the technique, this documentary offers a fascinating insight into the anime icon’s world.

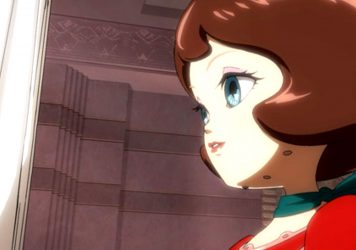

Through a series of interviews structured around his work in anime, this documentary highlights just how monumental Satoshi Kon’s all-too brief career was. Starting out as a manga writer and artist, Kon became a beloved figure in the world of animation with films like Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers and Paprika, his TV series Paranoia Agent – all complex, ravishing high points of the medium. Tragically, Kon passed away in August 2010 from terminal pancreatic cancer, diagnosed just three months prior.

Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist mainly focuses on Kon’s film career, opening with a brief history of his work in manga which it only returns to intermittently. Directed by Pascal-Alex Vincent (who also directed the retrospective profile doc Miwa: Looking for Black Lizard), the film boasts incredible access to some big industry names and people who knew Kon well, with interviews staged around the world so as to illustrate his far-reaching influence.

While the majority of the film is structured around his four feature films and TV series Paranoia Agent, sorting through the context, production details and reception of each, some of its most interesting moments are found around the edges of that structure. Several interviewees speak of Kon’s efforts to protect new animators, while others discuss how his experience with the anime and comic book industries filtered into his work, and the psychological strife of his characters.

Another fascinating digression comes from discussions of adaptations and collaborations that never were, most notably a segment which details Dreaming Machine, Kon’s never-to-be-completed fifth feature that is still mythologised to this day. Perhaps the film’s standout interviewee, Aya Suzuki, frequently notes how labour issues in the anime industry were intrinsically important to Kon’s work, and adds that Dreaming Machine was intended to nurture emerging animators – a mournful moment that reveals the true extent of what was lost with Kon’s passing.

For those who already know Satoshi Kon’s work, this is a worthwhile companion piece – strong in organising familiar information while offering fresh perspectives, although it is somewhat vague on the particulars of his artistic process. That said, the cultural context for Kon’s films is concisely presented, with the interviewees offering personal reflections on each. Lead actress Junko Iwao’s discussion of Perfect Blue is a particular highlight, conveying how Japan’s idol culture has impacted and commodified the lives of women.

There’s not much footage of Kon himself, which may enhance his enigma but feels at odds with how the film otherwise attempts to humanise him. It’s to the film’s credit, however, that it doesn’t evangelise him or shy away from showing his faults – one producer, Taro Maki, recalls how Kon told him he had “brought shame upon the industry” after struggling to secure funding for a feature.

When it comes to Kon’s work, the general focus here is on the themes rather than the technical aspects which set it apart – for instance, his highly-detailed method of storyboarding. There are a few exceptions: Masashi Ando, a character designer at Studio Ghibli who also worked on Paranoia Agent, talks through Kon’s approach to character design, noting that the industry as a whole is content to draw “cute girls and handsome boys” and how the imperfections of Kon’s characters were what made them special. Still, it’s a shame not to see further insight into how his manipulation of subjectivity distinguished him as an animation director.

Published 4 Aug 2021

Satoshi Kon’s cult anime contains a vital message for modern audiences.

The anime master behind Paprika and Perfect Blue left behind several incomplete projects which could still be realised.

Media, memory and film history collide in Satoshi Kon’s time-bending story of a faded screen star.