During the summer I was 17, I watched a lot of movies and had an existential crisis. I had just graduated high school, where I was the perfect student who had achieved the highest possible score for my final exams, but I had always known that I could never truly fit into my school’s and society’s expectations of perfection, because I was gay. I was educated to believe that queerness was shameful and wrong, and so I buried this knowledge as deeply as I could by distracting myself with academic success. But now, no one cared about how many A+s I had scored and I could no longer hide from myself. It was during this unmoored summer that I first came across Only Lovers Left Alive.

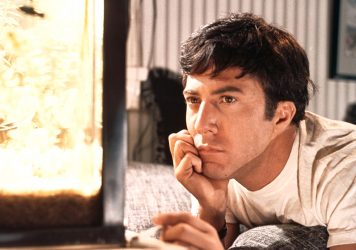

As I grappled with my sexuality, Jim Jarmusch’s tale of Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and Eve (Tilda Swinton) – two well-read, musical vampires who have been eternally in love – spoke to me. This story of their love triumphing against the odds, and the isolation that they experience over hundreds of years, felt intensely relatable to my experience as a queer woman.

Conceptualising Only Lovers Left Alive as a queer film might seem bizarre. Adam and Eve are so straight that they are named after the first heterosexual couple. But it’s not that simple. Being “queer” – to elude even the stricter labels within the LGBTQIA+ community – exemplifies what it means to exist in the blurriest spaces outside heteronormativity. Adam and Eve might appear to be male and female, but they certainly aren’t heteronormative. They are immortal, androgynous vampires who aren’t even human, let alone capable of subscribing to sexual and gender binaries. Their relationship evades the roles and narratives dictated by traditional social norms, and is an act of resistance against their world.

At its beginning, Only Lovers Left Alive characterises being in love as a very isolating, bleak experience. Adam and Eve are not just physically separated – in Detroit and Tangier, respectively – but they are displaced from the human world they float through. Both Adam’s and Eve’s apartments are silent and dark without each other, boarded up with cluttered books and separated from the rest of society by thick curtains and rickety staircases. The only way that the couple are able to connect with each other is through video calls, where they are each confined to tiny, glitching screens and are dwarfed by the sprawling emptiness of their physical lives. Their inability to survive in daylight hours entraps them within their domestic realms. Even when they enter the outside world at night, they are forced to conceal their bodies and to steal and traffic necessary supplies, connoting their lives with shame and denying them the freedom they desire.

At 17, I too felt that my love was lonely and shameful. In high school, it was made clear to me that I was not allowed to experience life like my heterosexual peers. I was taught in Religion and Sex Education – and even Science classes – that homosexuality was a sin, and everyone around me threw “gay”, in its derogatory pejorative, around as frequently as they might say “stupid”. Just like Adam, who becomes deeply depressed in reaction to his isolation, my entrapment within a homophobic world hugely affected my own mental health. Adam and Eve’s inability to live honest, free lives together, and their ostracism from society, represented exactly how I had been made to feel. Their experiences validated my own loneliness in a way that no one in my real life had ever been able to.

But, Adam and Eve’s love also brings them immense joy. In my favourite scene in the film, after their reunion, they dance to ‘Trapped By a Thing Called Love’ by Denise DeSalle. At that moment, nothing else matters to them. They gently interlace their fingers, twirl against each others’ bodies, and softly smile at one another. The camera breaks its previously reserved presence and floats above their bodies, centering their transcendent happiness. The small joy of sharing intimacy is, to them, so much more than a sweet moment — it is deeply healing, resisting the joylessness of their lonely existences.

Before they dance, Eve tells Adam, “You’ve been lucky in love.” This is the film’s biggest understatement. Sharing the world with one another brings both Adam and Eve the hope that their isolation is devoid of – and it is this hope that underlies their stubborn insistence at overcoming everything, simply to be together.

When I watch these scenes now, Adam and Eve represent the queer spirit to me. Throughout history, queer people have fought for the freedom to express their identities with pride and hope. Connection, community, and the simple right to exist authentically and happily have been (and, in many cases, still are) a radical form of resistance in a world where queerness has been met with violent oppression. Adam and Eve, similarly, exist in a society that is hostile to their identities, and where access to their supplies and community is precarious at best. To not only survive, but to love, exemplifies this same resistance. Watching them enact this inspires me to uphold my own queer pride.

But, as a 17-year-old, what Adam and Eve’s joy provided me with was much simpler – a flicker of optimism that I had never really felt before. It empowered me to consider that, maybe, I would not be destined to the life of secrecy and self-hatred I envisaged for myself – that, someday, as I learned to embrace myself, someone would dance with me too, and that I would experience a love like Adam and Eve’s. It made me realise that the prejudice I experienced could not stop me from attaining the joy I craved.

The last time I watched Only Lovers Left Alive was six months ago, several years out from that summer. I held hands with my partner as we watched it together, both of us as enraptured by it as I was as a teenager. But it doesn’t resonate with my loneliness anymore. Now, Adam and Eve celebrate what queer love means to me, as a proud lesbian in love with another woman: something beautiful and undefinable and unquashable, and the most important thing in my world.

Published 13 Dec 2022

The Lisbon sisters helped me to understand my own awkward coming of age.

By Henry Bevan

Mike Nichols’ 1967 film is a great tonic for anyone suffering from post-university blues.

By Emily Bray

To the kids with the “coolest jobs on earth”, being yourself is all that really matters.