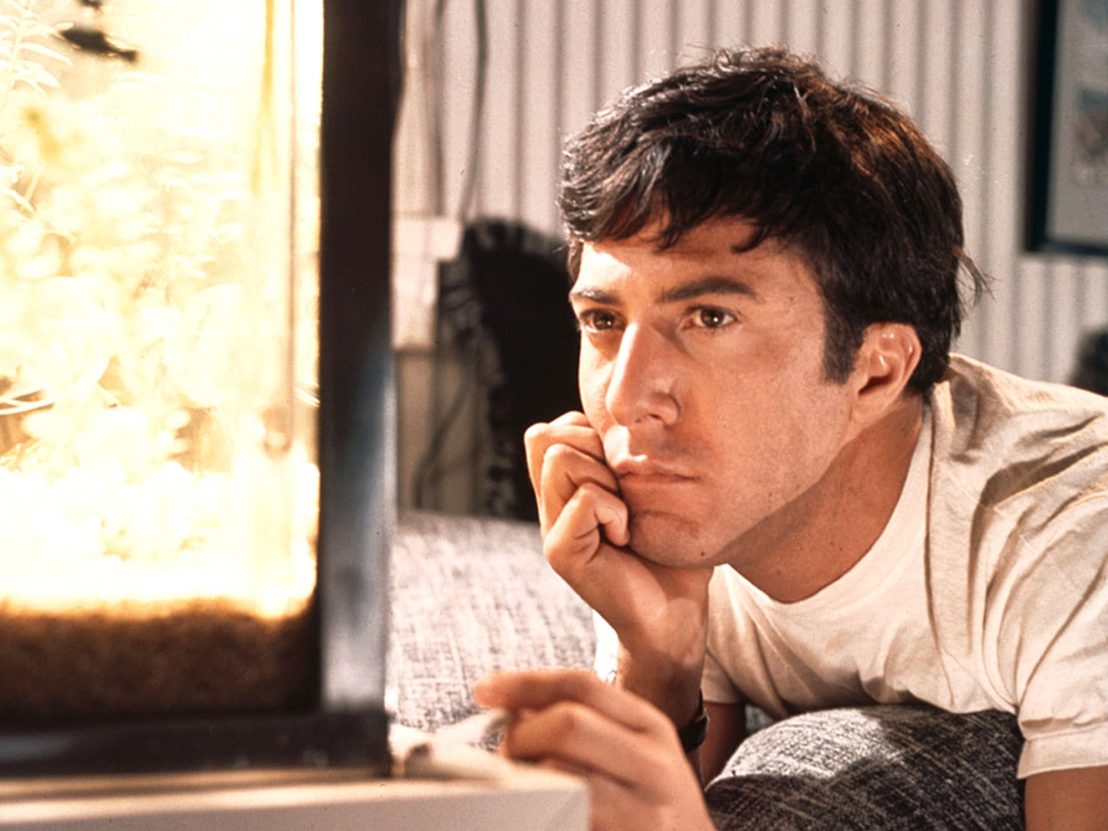

Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) knows how daunting graduating university is. As the travelator glides him towards the next stage of his life, his fidgety face shows he is nervous. He understands what I’ve just discovered. After you get your degree, your life becomes uncertain. You worry about how you will pay your rent, you learn some friendships are circumstantial and you feel the pressure to get a job worthy of the work you’ve done during the last three years. It’s hard watching the The Graduate, which turns 50 this years, and not making Ben’s story about me.

When The Graduate was released in 1967 it was dismissively labelled as a “sex comedy”. While the film is funny and features sex, its priorities lie in creating a touching portrait of anxiety and the dislocation from society you feel when you experience the post-university blues.

Director Mike Nichols reveals Ben’s unease in an early dinner party scene. His well-meaning but self-indulged parents, brilliantly played by William Daniels and Elizabeth Wilson, host a get-together to celebrate their son’s recent successes. The camera is held in a tight close-up of Hoffman’s face as he telegraphs his character’s confusion: are the guest celebrating or criticising him as they relentlessly interrogate him about his future? By the end of the scene, you feel as if you’re suffocating as Ben stumbles over basic answers. You want to escape the party alongside him.

It is Anne Bancroft’s Mrs Robinson who orchestrates his rescue. The bored housewife takes him home from the party in her attempts to seduce him, and by doing so she presents him with a fantasy that will act as a release valve for his dissatisfaction. She knows Ben needs to be seduced as the expectations placed on him are crippling him. Like all graduates facing their new reality, Ben needs a blissful distraction from his unfocused life. He needs drive, and Mrs Robinson is more than happy to be part of his life as long as he does what she says: namely, go nowhere near her daughter Elaine (Katherine Ross).

Nichols and writers Buck Henry and Calder Willingham relish skewering the adult characters, showing that even though they think they’re doing right by their children, the pressure they put on them contributes to their graduate malaise. Mr Robinson (Murray Hamilton) forces Elaine to leave college so she can marry a man. He does this because he believes it’s what’s best for his daughter, even though she wishes to stay. She gets into a funk and responds by running off with Ben, a man he labels as a “degenerate”. Ben’s ennui sinks in as he doesn’t want to disappoint his parents because “they don’t deserve” it. His dislocation is a direct result of the pressure he feels his parents are placing on him. If there wasn’t any expectation placed on him, he wouldn’t be in this situation.

It would be selfish and naive to blame the dislocation some graduates feel entirely on their immediate surroundings, but Nichols’ film is told exclusively from Ben’s perspective, and he needs someone to blame other than himself. He explains to Elaine that he feels like he is “playing a game and the rules don’t make any sense.” Like an angsty teen, he acts out against his parents, who brag constantly about how much they’ve done for him.

One of the film’s most iconic images is of Ben submerged in a swimming pool wearing an oxygen tank and flippers – a potent metaphor for how overeducated and underemployed graduates are. The have been given the best possible career preparation, but unless they belong to the small percentage who join graduate schemes, they end up working menial office jobs or, as in my case, in a shop where every time I scan an item the corresponding beep repeatedly screams YOUR LIFE SUCKS. And, instead of doing anything about our predicaments and proving we are as smart as we say we are or the piece of paper we were given when we graduated says we are, we sink deeper into the pool reminiscing about the time and place where we were successful: university.

Yet Nichols proves nostalgia for our past successes isn’t a cure for malaise. When Ben stalks Elaine back to Berkley he is returning to a college where he finds he is no longer welcome. His landlord immediately dislikes him because he is “drifting”, as he is neither a student nor employed. Other characters reject Ben for stepping off his predetermined life path, and as he boards the bus with Elaine he realises life will always be filled with uncertainty.

That penultimate shot is famous for its stillness, but the real final shot is the bus pulling off into the distance. Throughout the film Nichols displays an obsession with movement, be it through the use of long takes in the dinner party scenes, in later shots of Ben speeding across town on his date with Elaine, or the travelator at the very beginning. The message is clear enough. You can try to turn around but you’ll still keep moving in the same direction. So you better just embrace life.

The Graduate is back in cinemas 23 June as part of the BFI’s Dustin Hoffman season. Fore more info visit whatson.bfi.org.uk

Published 1 Jun 2017

Don Siegel’s period thriller shows this icon of screen masculinity at his most pathetic and vulnerable.

The American actor’s reemergence in I Love Dick serves as a reminder of his rare talents.

Mickey Rourke is perfectly cast as Hank Chinaski in this down-and-dirty picture from 1987.