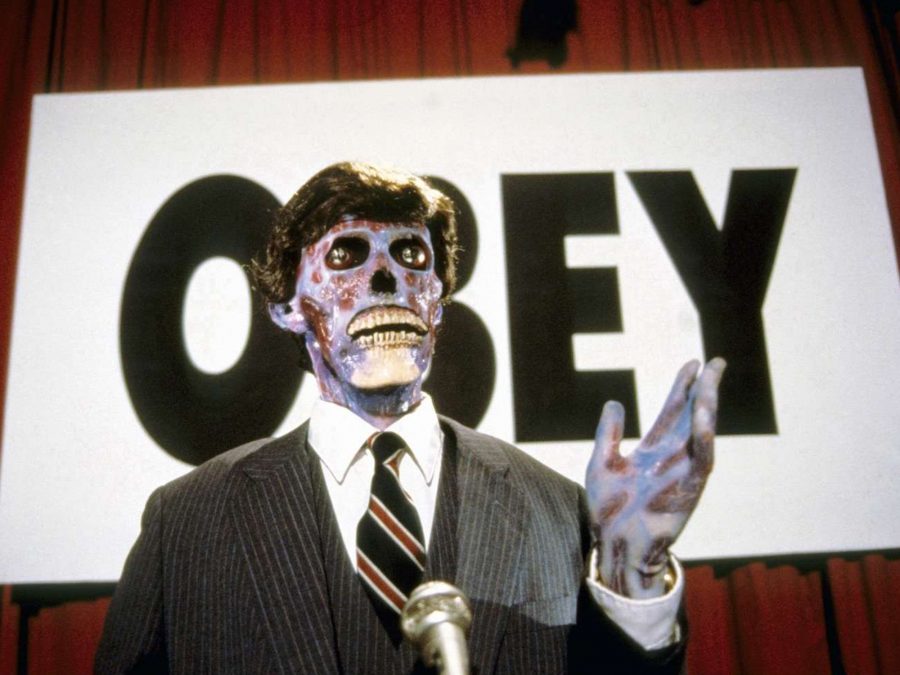

On 4 November, 2018, John Carpenter’s They Live turns 30. This date also marks the two-year anniversary of the 2016 US presidential election, where a former reality TV star was elected. Carpenter’s film is a political and social thriller posing as an alien invasion sci-fi. Aliens have invaded earth and employ coded television transmissions to assist them in their desire to control the human population.

Accompanying these messages are what appear to be a precursor to the modern-day drones which now control our skies. The true conflict, not only within the film, but also surrounding it, is the controlling influence of television and how this conflicts with ideas of free will in the West.

One conflict addressed in They Live is that of film versus television. Beginning in the late 1970s, the competition for viewership supremacy actually brought about a change within filming methods, as most films would eventually be watched on a television. Television is better viewed with different aspect ratios and viewing qualities than film. According to film historian Emilie Bickerton, in order to retain home viewership after a film had been shown in theatres, films were preemptively shot to accommodate a television viewing experience.

A further issue was that television had a greater susceptibility to advertising and the demands of television executives in a manner that cinema – especially independent cinema – did not. They Live is a critique of both television and advertising, with Carpenter rallying against ratings hungry network executives and the insidious, controlling influence of advertising. It’s a work that combines science fiction and horror elements in which Carpenter makes a compelling statement relating to the real world – that film can be a weapon which fights the social coercion of television.

In They Live, we are never explicitly shown that humans can read or are directly affected by the transmissions. What we do see, however, is that the aliens have positioned themselves as the upper class elite, and humans emulate these hidden alien overlords. This is very similar to how advertising ideally works in the real world – individuals are exposed to product advertisements, as they themselves respond to the advertising other people are influenced by and make the same or similar decisions and purchases.

The genius of Carpenter’s film lies in how it shows the advertising model trickle down from powerful aliens to ordinary humans, effectively marking it as an incisive comment of 1980s yuppy culture. They Live has been heralded by both Liberals and Conservatives as the exemplification of 20th century advertising and social control, just as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis was embraced by the Nazis as well as Allied countries for its portrayal of the dangers of modernity. The question of what it meant to be a human being in a time when you were expected to be a cog in the machine was a relevant and important question.

Both Metropolis and They Live speak to the different ways in which the major conflicts of their respective days challenged popular notions of identity. During the 1980s, the issue that endangered free will was external manipulation which came in the form of television transmissions, and their prescribing of lifestyles which were beneficial to the power structure. Giving these issues a platform is what good film does; it makes important issues prominent in an approachable manner.

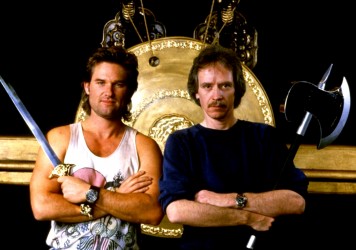

Carpenter tapped into the anxieties of the 1980s in a totally unique manner; the combination of wrestling theatrics in the form of protagonist “Rowdy” Roddy Piper’s one liners and action scenes, combined with social commentary surrounding surveillance and brainwashing contribute to the argument that They Live is one of the most important and pertinent social satires of the later 20th century. Now more than ever it is vital that we heed Carpenter’s warnings; to question whether the decisions we make are truly our own, or if television and advertising are coercing us.

Published 10 Sep 2017

He may be all but retired from feature filmmaking, but traces of the genre director’s legacy can be found everywhere.

The cult director talks remakes, his love of early synthesisers and why nostalgia works in mysterious ways.

Three decades on from its release, just how accurate was Paul Verhoeven’s classic dystopian sci-fi?