The cult director talks remakes, his love of early synthesisers and why nostalgia works in mysterious ways.

Every great artist eventually reaches a point where it becomes apparent that their best work is behind them. In all likelihood John Carpenter will never again reach the heights of his ’70s and ’80s pomp – in the five-year period between 1978 and 1982 he directed Halloween, The Fog, Escape from New York and The Thing – but while he may not be turning out era-defining genre classics at the same astonishing rate, the 68-year-old cult icon is showing no signs of slowing down. Having not occupied the hot seat since 2010’s tepidly-received psychiatric chiller The Ward, Carpenter has seemingly entered an exciting new phase in his career.

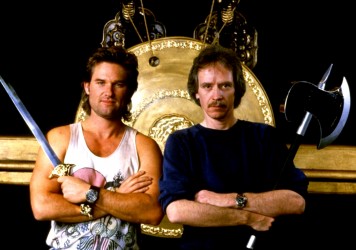

Building on his earlier acclaimed work as a film composer, in 2014 (on Halloween, no less) Carpenter released ‘Vortex’, the debut single from his first ever stand-alone studio album. Comprised exclusively of original non-soundtrack material, ‘Lost Themes’ represented both a natural extension and a significant evolution for the veteran filmmaker, returning him to the forefront of the cultural discussion surrounding the intersection between movies and music. A follow-up album, ‘Lost Themes II’, arrived in 2016 along with the announcement that Carpenter would be hitting the road with his son, Cody Carpenter, and godson, Daniel Davies, to play his first live shows.

Carpenter’s trademark synth is present on both ‘Lost Themes’ records, but unlike the distinctly minimal scores he created for all but four of his 19 feature films (the outliers being The Thing, Starman, Memoirs of an Invisible Man and The Ward) the addition of electric and acoustic guitars lends these new songs a fuller, more melodic sound. Carpenter describes ‘Lost Themes’ as “soundtracks for movies in your head,” and indeed there’s something uniquely compelling about listening to music which is unmistakably score-like in composition and tone but which exists without the need for accompanying visuals. We spoke to the horror maestro about life as a touring musician, cinema’s digital revolution, and why he’s open to remakes of his films.

LWLies: You’ve recently started touring for the first time. How has that experience been for you so far?

Carpenter: It’s been fantastic. The biggest thing for me is I get to play with my son and my godson. And the other band members we have, the rhythm section, are Tenacious D’s band, and they are just the greatest. So far it’s been a wonderful experience. The shows have gone pretty well. It’s primarily a career retrospective show, we’re looking at some of the scores from my old movies. The audience seems to dig them so that’s nice.

There seems to be a renewed interest in your film score work. What do you put that down to?

I can’t explain it, it’s just luck I think. There seems to be a nostalgia for an old synthesiser sound, which probably has something to do with it. People recognise that sound from my movies but what’s funny is that I started using synthesisers out of necessity, because it was the cheapest thing available to me at the time. If I was starting all over again I would probably still use the same synthesisers, but of course the technology has advanced so much that I would be able to create completely different sounds. Digital synthesisers are the best.

What’s your feeling about the move from film to digital?

There are reasons for moving to digital in film. I’ve seen a comparison side by side and it’s really interesting. A lot of purists want to go back to using film, but there’s no going back now so you’ve got to keep moving with the times. The only problem with digital is it doesn’t hold up, you have to keep a copy on film because it just degrades. In terms of the sound, I’m working on a computer, off of audio plugins which you can purchase and play around with – man, the range you can get from them is just astonishing. I don’t know if better is the right word, but it’s pretty cool.

Which film composers did you most admire when you were starting out?

Movies in general were very, very important to me when I was young. They loomed very large in my life, and the music was equally as important. I was influenced by the early great composers like Bernard Herrmann and Dimitri Tiomkin. These guys were the real pioneers. As time went by I got into groups like Tangerine Dream, they did a score for a movie called Sorcerer which is just astonishing, that really blew me away when I first heard it. And also the work of Goblin, that was important for horror cinema. The first electronic score I ever heard was for a movie called Forbidden Planet back in ’56. There was absolutely no orchestral music in that, it was all electronic, and I’d never heard anything like it.

Do you think orchestral scores are overused today?

Well, they sure are used a lot. They’re still considered the best, you know, anyone can play a synthesiser. I have very minimal chops, which is why I say that. So there’s a little bit of snobbery involved. But then you have a guy like Hans Zimmer, who blends orchestral and electronic music really well. His scores are always very memorable.

What was your process when you were starting out?

It was very improvised. When I was writing those early scores I wasn’t watching the films, that only came later. So initially I would write and play the music and once I had four or five different pieces I would cut them into the movie. The first time I scored to the image was Escape from New York in ’81. But I could sit down with a deep bass computer sound and start from there. You’re trying to create a mood, so as soon as I have that initial note I can start feeling my way around. The process has evolved and I’ve evolved as a musician, but it’s still about trying to create a mood and build an emotional connection.

Why was this the right time in your career to go into the studio for the first time and record an album?

To tell you the truth it just sort of happened. The record label heard the music and expressed their desire to release it, which was something I had wanted for quite some time. I don’t know what will happen next though. I tend to take things as they come nowadays. I was pretty ill last year so every day that I’m above ground is pretty exciting.

Have you been approached in the past to write scores for other people’s movies?

Yeah, but nothing I ever really wanted to do. I’d be open to something that interested me. I’ve always been focused on my own stuff though. I’ve got a couple of things cooking right now, nothing imminent, but we’ll see what happens there.

Quite a few of your movies have been remade in recent years – and there’s even a Starman update in the works. How do you feel about that?

Ah you know, it’s okay. They won’t destroy my originals. They’re still there, people still watch them. I just prefer that when they remake my movies they pay me. That’s always a bonus. But I’m never involved in the process so it really doesn’t matter to me.

There’s an interesting story about Ennio Morricone using some of the music he wrote for The Thing for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight…

See, that’s just weird. The Thing was the first movie I did for a major studio, and they didn’t want me to do the score. So they brought in Ennio which was an amazing for me because he’s one of the greatest film composers of all time. I don’t speak Italian, he doesn’t really speak English, but we worked pretty closely together and it worked out great. I have no problem with the fact he ended up using some of the music he wrote for The Thing on another movie.

What do you love about movies?

Movies are the art form of the 20th century. More so than music, I think. They’re transcendent, they can be shown and enjoyed in any country in the world. Especially horror movies – people all over the world get scared about the same things, it doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from. I’m scared of a lot of shit. I don’t want to die. But we’re all headed for the big dark, so what the hell.

John Carpenter is currently on tour across the UK. ‘Lost Themes I & II’ are both available from Sacred Bones Records.

Published 26 Oct 2016

By Ewen Hosie

Released 30 years ago, John Carpenter’s frantic San Francisco beat ’em up has lost none of its cult appeal.

By Lara C Cory

The cult director has recorded new versions of Halloween, Escape from New York, Assault on Precinct 13 and The Fog.

He may be all but retired from feature filmmaking, but traces of the genre director’s legacy can be found everywhere.