Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood may take place in the early part of the 20th century, but the political and economic landscape which Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) presides over seems uncomfortably familiar in 2017. The film introduces us to an America at the crossroads of capitalism and religion before ruthlessly decrying both constructs over the next two hours. In Plainview’s ascent from lowly miner to oil magnate, Anderson chronicles the birth of a brave new industrial age, which results not only is vast wealth for the country but also the tweaking of its moral compass.

Communities hit hard by recession look for anything to cling to: a man promising a return to prosperity doesn’t have to do much to take advantage of them. Plainview’s well-rehearsed sales pitch is firmly recited and resolutely convincing. By projecting strength in a time of anxiety, his handsome proposal wins over scores of citizens at town hall meetings, and he gladly accepts the oil rights being handed over. What these people don’t know is that Plainview is offering mere trinkets for precious tracts of land, and the little money they make will pale in comparison to the fortune he acquires by drilling. Still, his deplorable behaviour is rendered wholly acceptable at the mere prospect of riches.

While wealth was very much a beacon of morality in the early 20th century, Plainview has done terrible things to amass his. He masks this side of his personality by presenting himself as a family man. It doesn’t matter to the locals that HW (Dillon Freasier) is not actually his son, and that Plainview will send ship him off to a care home once he becomes a deterrent to his business. Meanwhile, when workers on the drill site die, Plainview scrubs all evidence of their time there as quickly as possible. The people of Little Boston are prepared to overlook Plainview’s intentions because they so desperately need the new jobs and economy that his business will bring.

You might reasonably assume that the core theme of There Will Be Blood is the conflict between commerce and the church, but this is not entirely accurate. While Plainview and Eli Sunday (Paul Dano) frequently butt heads, both are competing for the same well of black gold. Sunday is at the forefront of evangelism and preaches that virtue will be rewarded by the almighty dollar. Religion is a business to Sunday and he practices it well: for a fee he acts as God’s conduit, offering sinners a fresh start. Sunday, for all of his demure piety, also places a high values on capital gain – and Plainview knows it.

It’s during Plainview’s baptism that Paul Thomas Anderson really drills down into the intersecting evils of capitalism and religion. Kneeling in front of the churchgoing masses he loathes, Plainview is bathed in the cross-shaped light from above, revealing a soul battered in exchange for material wealth. Eli isn’t doing this for his rival’s salvation, however, but in order to humiliate him. Neither Plainview nor Sunday desires to make Little Boston a better place: they only hope to enrich their own lives and finally be rid of this dustbowl town. Each man would sooner put the other, and everyone else, underground before relinquishing this shared aspiration. Business isn’t the only zero-sum game here – now, so is life.

“I have a competition in me,” says Plainview, “I want no one else to succeed.” Later on, hermetically sealed inside his mansion, he appears to carry on solely to inflict punishment on past adversaries. Even the success of his own adopted son proves unbearable for the oil baron, and he disowns HW. Unable to see past his own faults, Plainview rebukes his fellow man for his deep-seeded hatreds. In the case of Eli Sunday, he condemns his rival to death.

There Will Be Blood is a compelling look at what happens when a sociopath – someone with no scruples in any regard of his life – gains power. The kind of man not dissimilar to one who will soon have control of the world’s largest military and the codes to a nuclear arsenal. Only time will tell whether the American public is destined to suffer the same fate as Little Boston. More than a hundred years later, the mythologising of self-made men still obfuscates the truth.

Published 25 Jan 2017

By Tom Williams

Bret Easton Ellis and Mary Harron’s caustic vision of ’80s consumerism is sadly back en vogue.

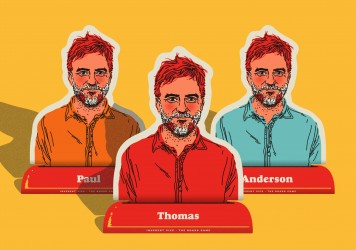

The prodigiously talented Inherent Vice director reveals what makes him tick.

Andrew Dominik’s 2007 biopic humanises America’s most storied outlaw.