Twenty nineteen. Say it out loud and it almost sounds futuristic. The movies knew it, too. A spate of ’80s-produced science fiction films chose to establish their milieu specifically in the year 2019 – but why was this? A brief bit of numerological research tells us that 2019 promises creativity, self-expression and alignment, all of which sounds pretty positive. Yet, perhaps unsurprisingly given everything that was going on in the 1980s, sci-fi filmmakers offered an undeniably grimmer outlook of 2019.

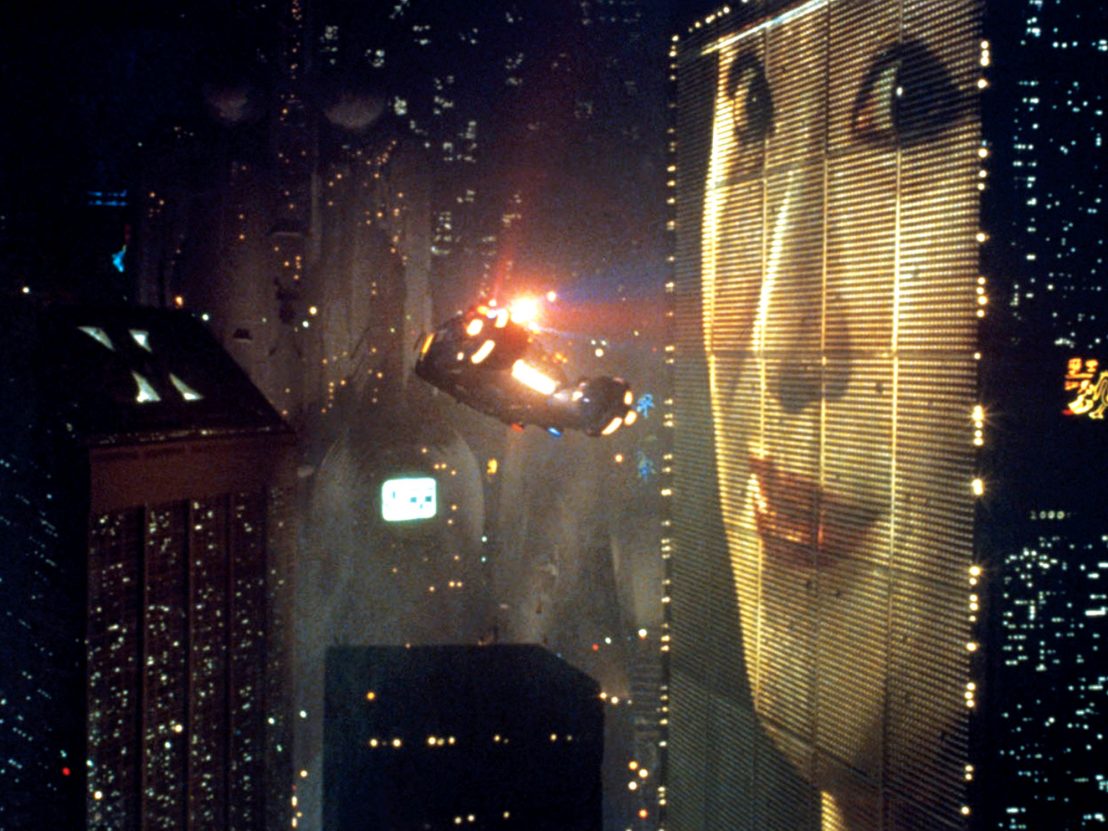

Take Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Its breathtakingly bleak establishing shot of a dystopian Los Angeles circa 2019, replete with cold, corporate megastructures and hellish flames, merits a mention in any conversation regarding cinema’s greatest openings. You’ll find creativity here too – just as the numerologists predicted – but in the film’s alternate 2019 the creativity of humanity has resulted in the spawning of the species’ successor. The Nexus 6 breed of replicants are superior to human beings in every way. In Scott’s dark prophecy, it seems the age of man is drawing to a close.

Humanity’s inescapable demise is evident in every level of Blade Runner’s conceptualisation: from the empty, post-modern layering of neon and light over the crumbling ruin of 20th century architecture, to the cynical, moral emptiness of Harrison Ford’s protagonist Rick Deckard. The titular blade runner believes himself to be human and yet memorably in the film’s climactic moments is taught a fateful lesson on the richness of life – by a sentient machine, no less.

Above all, Blade Runner emphasises humanity’s capacity for self-destruction: ecological disasters, continuing economic polarisation, the growing power of corporate structures and the emergence of soon-to-be-sentient AI all strengthen the film’s prophetic vision of the future. On the other hand, the film also predicted that Atari and Pan-Am would be major features of an advert-laden skyline by this point, so maybe Scott’s crystal ball didn’t see everything.

Blade Runner’s belated sequel, set in 2049, is itself backdropped by the increasingly real prospect of a global food crisis. However, this particular doomsday forecast is nothing new for science fiction: 1987’s The Running Man, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger as wrongly convicted everyman Ben Richards, also takes 2019 as its setting and is characterised by mass famine and violent riots. Even as far back as the early ’80s, the original mind behind the film, Stephen King (writing under the pseudonym Richard Bachman) understood that no matter how dire the situation may be, no one will pay much attention so long as there’s something decent on the telly.

In The Running Man, television is the opiate of the masses, with average American citizens too readily caught up in deadly gladiatorial combat shows to worry about the fact that food is running out, or that art, communications and music have all been banned. Much like Blade Runner before it, Paul Michael Glaser’s film was ahead of its time in predicting that 2019 would result in omnipresent companies no longer masking their true intentions.

Here, America’s new corporate superpowers wear their naked greed on their figurative sleeve – quite literally in the case of sportswear brand adidas, who agreed to have their logo plastered all over the official jumpsuits of the film’s titular game show, where contestants are hunted down and slaughtered live before a baying studio audience.

The show within the film is presented and masterminded by Damon Killian (Richard Dawson), a master of misdirection and ‘fake news’. Not only does he use the show as a way of disposing with inconvenient whistleblowers who are ready to rat him out, but at several points during the film he has video footage doctored to present his own version of the truth. We now know, of course, that the American people throwing their lot in with a populist, media-spinning public figure is not as far-fetched a prospect as it may once have seemed.

Foreshadowing the rise of a Trump-like figure is not all that The Running Man got right. Its somewhat idiosyncratic view of the future also features voice-activated smart homes, as well as the rise of reality TV. One crucial plot point from the original 1982 novella left out of the film sees a desperate Ben Richards trade his life to destroy the insidious Games Network… by flying a fully-fuelled passenger airliner into the broadcaster’s skyscraper headquarters.

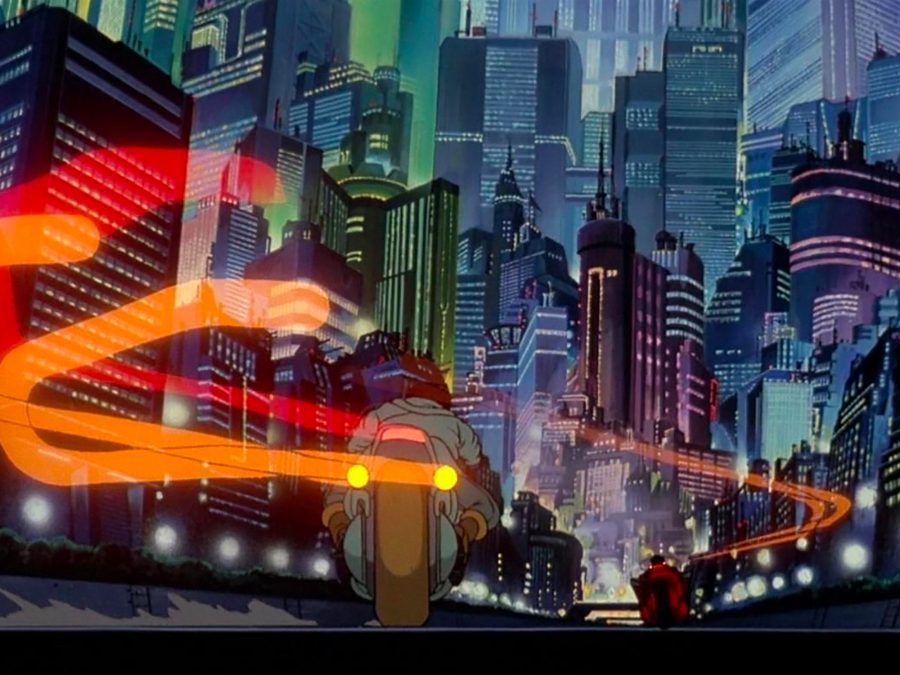

But perhaps science fiction cinema’s most accurate prediction for 2019 can be found in Katsuhiro Ôtomo’s seminal 1988 anime, Akira. In this cyberpunk classic, Neo-Tokyo is to host the Olympic Games in 2020, the original city having by reduced to rubble during World War Three – so, on second thoughts, maybe not so prophetic after all. The film also envisioned unruly motorcycle gangs ruling the streets by 2019, but a moral panic followed by stringent new laws passed in the ensuing decades have made motorcycle gang membership far less popular than before.

The motorcycles of Akira do form an unmistakable part of the film’s iconography though. And with many of them plastered with corporate branding, this is yet another dystopian sci-fi about the pervasive nature of all-powerful corporations in the throes of late-stage capitalism.

Meanwhile, 2005’s The Island benefited from making its 2019 predictions from a much closer vantage point. The lurking spectre of rampant corporatisation is still evident, both in the film’s plot and in sportswear brand Puma’s decision to dress the film’s soon-to-be-organ-harvested inhabitants. Even more troubling is the key plot device that underpins the film: a group of clones are held captive until the time comes that their double requires their vital organs, a production-line approach to human organ harvesting which has allegedly been occurring in China for decades in so-called ‘black jails’.

In a horrifying inversion of the film’s premise (where both the subjects and the world at large are unaware of the source of said organs) the law in China surreptitiously supports this barbaric practice, with a 1984 provision stating that executed prisoners can be used as donors, despite this statute flaunting several international human rights laws.

And so, as humanity stumbles its way through the early stages of 2019, take a moment to consider the days ahead. Will some remarkable AI creation develop sentience before we’re able to pull the plug? Perhaps the End Times are already here and you’re too busy watching the TV to notice? In fact, are you even sure that you are you at all? If science fiction cinema has taught us anything about these four, seemingly innocuous digits, it’s that no matter how we intend to approach this year as a race, we need to be very careful indeed.

Published 9 Feb 2019

By Harry Harris

Though similar, there are marked differences between these twin films – and the fates of their respective directors.

By Nadine Smith

Like Philip K Dick’s replicants, Kurt Russell’s steely-eyed space marine asks what it means to be human.

Filmmakers like Christopher Nolan and Alex Garland are stoking our curiosity and critical thinking, but they’re in the minority.