When Jane Fonda arrives midway through Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth, the tenor of the film shifts. Donning a peroxide blonde wig, she is fading Hollywood star Brenda Morel, and though Fonda is barely on screen for a few minutes, her monologue teems with bitter, caustic invectives. The character recalls the catalogue of actresses Fonda has played – often so brilliantly – throughout her career: from Gloria, the American loser fighting her last war in Sydney Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, to Bree, the actress-turned-call-girl who longs for human connection in Klute.

Perhaps the most obvious point of comparison, however, is Sidney Lumet’s 1986 film The Morning After, which netted Fonda the most recent of her seven Oscar nominations. Like Gloria and Bree before her, Fonda’s Alex Sternberg is an actress whose dreams never quite materialised. When we meet her, the promise of her early career has all but faded, leaving her embittered and rudderless.

Lumet’s film is premised on a wafer-thin murder mystery. Alex wakes up next to a male corpse and isn’t sure whether she killed him in a drunken stupor. These conventional thriller elements occupy more real estate than the script’s more compelling latent character study. Today it exists as an outlier in Lumet’s filmography, and with good reason. As a result, Fonda’s excellent work in the film has gone overlooked for too long.

One standout scene sees Alex share a late-night drink at her apartment with Jeff Bridges’ benevolent cop, Turner, who waltzes into her life by chance. Somewhat inexplicably, Lumet frames the two in a long shot, meaning we get no sense of the alchemic rapport between them until the camera movies in on Fonda. What follows is a monologue of pain and pride. “I am an actress,” she croaks. “Was. I was even good.” A few drinks in, Fonda wears a mask of proud defiance, as if seeking to justify her bygone glory to both herself and Bridges, stubborn in her refusal to crumble.

In the context of her acting career, Fonda’s performance in The Morning After is a tonic – a return to form in which she did not blunt her edges, playing a wised-up woman with a low tolerance for bullshit. Fonda spent the ’60s as a would-be starlet, subjected to playing spritely naifs in the likes of Barefoot in the Park and Barbarella. With Horses and Klute, she challenged the public perception of her, and off-screen began flirting with political activism. In the late ’70s vanity projects such as Coming Home and The China Syndrome retold the story of her own radicalisation – Fonda playing women who kowtow to the men in their lives yet, following moments of political nirvana, grow into animals of conviction.

Her activism and acting made her an symbol of American womanhood in an era of cultural revolution. Yet on many occasions, Fonda chastened herself, deigning to her characters’ naivety. In her 2006 autobiography, ‘My Life So Far’, Fonda writes at length about the formal training she received at the hands of famed acting coach Lee Strasberg. With his help, Fonda trained herself out of her own belief that she didn’t deserve stardom, lowering her faint voice an octave to tackle roles like Gloria and Bree. In a very literal sense, she found her voice. Fonda has worn many faces, from coquettish ingenue to political firebrand to fitness maven. Yet The Morning After reminds us of something even more compelling and real: an actress deeply insecure about her own artistry.

Published 12 Jun 2016

A previously lost film provides a fascinating insight into the actor’s unorthodox creative process.

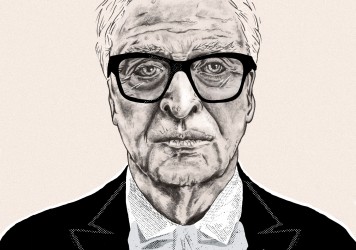

The British screen icon reflects on his remarkable career ahead of his starring role in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth.

Is it possible for women to love movies which promote a regressive, misogynistic worldview?