As Disneyland turns 60, we turn back the clock to gauge the cultural impact of the most enchanted corner of the Magic Kingdom.

If you were to present an atlas to any man, woman or child circa 1955 and ask them to locate the happiest place on Earth, their finger would invariably drop on Anaheim, CA. Built in just one year at an estimated cost of $17m, Disneyland first opened its gates at 2:30pm on Sunday 17 July, 1955. For the American people it was a day of celebration and ceremony not seen since the 1939 World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows.

After being introduced to his adoring public by actor and future president “Ronnie” Reagan, with network television cameras poised to capture this momentous occasion, Walt took the mic: “To all who come to this happy place: welcome. Disneyland is your land. Here age relives fond memories of the past, and here youth may savour the challenge and promise of the future. Disneyland is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts that have created America… with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.”

Through the sheer conviction of his ambitious vision, Disney had captured the imaginations of not just those in attendance — including VIPs Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis, Jr — but everyone watching at home. For the international media outlets reporting on the grand opening, it was a different story. As scores of workers furiously applied the finishing touches to the park, several rides broke down shortly after opening while a gas leak forced some areas to be temporarily shut down.

Worse still, a record heatwave coupled with a plumbers’ strike made things particularly uncomfortable for the 28,000 invited guests (many of whom gained entry via counterfeit tickets) who shuffled eagerly down Main Street towards the already iconic Sleeping Beauty Castle. Despite the resulting lukewarm press coverage, Disneyland was an instant and unprecedented success, welcoming an estimated 3.6 million visitors in its first year. Put simply, the Magic Kingdom was unlike anything the public had ever seen.

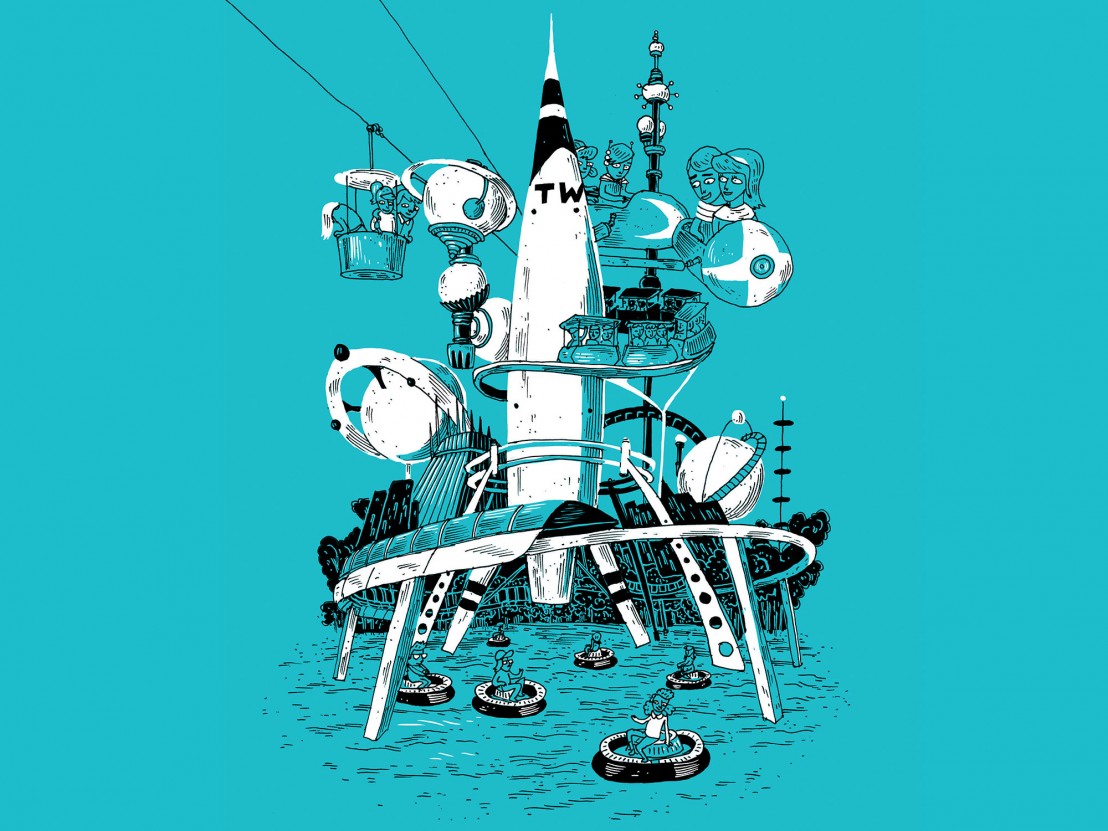

Boasting 18 rides spread out across five themed “lands” — ‘Main Street, USA’, ‘Adventureland’, ‘Fantasyland’, ‘Frontierland’ and ‘Tomorrowland’ — Disneyland was a miraculous spectacle, an awesome feat of American engineering where families could soar through the sky on Dumbo or take a stroll through the original sets from the 1954 adventure film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. In the space of a few short years, Disney had taken a 160-acre plot of orange groves in Southern California and turned it into one of the country’s hottest tourist destinations. The park’s commercial viability had been anticipated to some degree, but not even Disney could have predicted that his dream would — for better or worse — become a symbol of American culture both at home and abroad for generations to come. Yet the key to Disneyland’s widespread appeal was not the mass culture product that was being sold but something the public subconsciously craved far more than inexpensive thrills and plush merchandise: an ideology.

Situated on the east side of the park, Tomorrowland was initially conceived around what the world might look like in 1986. (Why 1986? Because that was the year Halley’s Comet was set to return to our skies.) According to Disney, this was the place where, “our hopes and dreams for the future become today’s realities.” Even for 1950s America, this was a romantic sentiment. Crucially, however, Tomorrowland was not “a stylised dream of the future, but a scientifically planned projection of future techniques by leading space experts in science.” This was a far cry from the chintzy boardwalk arcades and kiddie-oriented Coney Islands that had come before. What Disney had created was far superior both in size and scope. Something unifying and universal.

At the Tomorrowland dedication, white doves were released — “harbingers of peace for the world of tomorrow.” Later, during the live opening ceremony telecast, Disney himself commented, “Tomorrow can be a wonderful age. Our scientists today are opening the doors of the space age to achievements that will benefit our children and generations to come. The Tomorrowland attractions have been designed to give you an opportunity to participate in adventures that are a living blueprint of our future.” It’s easy to look back at this bold idealism with quaint fondness, but American society underwent a pronounced transformation during the Eisenhower era, exemplified by a constantly shifting public perception of what constituted ‘modern’.

The automobile revolution and the rise of the nuclear family dovetailed to spark a population boom that gave rise to a great suburban sprawl (California alone grew by 49 per cent in the space of 10 years). Tomorrowland tapped into this postwar restlessness, featuring more rides and moving attractions than any other area of the park. Visitors could climb into an Astro-Jet, pilot their own personal Flying Saucer, hop on the Alweg Monorail or take in aerial views of the park via the Swiss E-lift inspired Skyway.

In addition, Tomorrowland offered escapism from the mounting sense of national anxiety and paranoia brought on by the Cold War. Average Americans feared the Bomb and saw Communism as a genuine threat to their civil liberty (Disney himself had been a founding member of the anti-communist group Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals). Disneyland provided sanctuary, cocooning people in the wholesome family values they recognised as their own. As reporter Gladwin Hill observed in his 1959 New York Times’ article, ‘The Never-Never Land Khrushchev Never Saw’, “Disneyland is less an amusement park than a state of mind.” But this seemingly auspicious wonderland was not entirely pure.

Budget cuts meant that Tomorrowland opened without several of its planned attractions, the empty space being reluctantly leased to corporate sponsors. There was the Monsanto Hall of Chemistry, the American Dairy Association Dairy Bar (“nourishment for the future!”), American Motors’ A Tour of the West, presented in Circarama (a gigantic 360° cinema screen), and the somewhat peculiar Crane Paper endorsed Bathroom of the Future. These educational attractions were harmless enough, but collectively they became the ultimate representation of American consumerism.

In its promise of a brighter future, Tomorrowland offered hope to ordinary Americans, regardless of their social status. Yet it pointed down a predetermined path, the foundations of which were laid in a well-established system of capitalist ideals. It’s telling that Disney intended visitors to exit the park via Tomorrowland, empowered by a renewed belief in American exceptionalism.

Despite what the name suggests, Tomorrowland was not simply an evocative projection of an aspirational future, but a tangible utopia anchored in the present. One of Tomorrowland’s original and most visited attractions was Autopia, a mile-long asphalt circuit which kids could race around in miniature motorised cars at a top speed of 11 mph. Within a few years of the park opening, President Eisenhower would sign the Interstate Highway legislation, paving the way for the first multi-lane highways. Some rides, such as the Flying Saucers (a cross between bumper cars and air hockey), were more experimental than practical, but by and large Tomorrowland was inspired by real-world technological know-how, much of which was already being rolled out on an industrial scale.

Tomorrowland was a place where people could come together to acknowledge America’s industrial, scientific and technological enterprise while basking in the optimistic glow of the next chapter in their nation’s manifest destiny. This forward-thinking was typified by Disney’s personal fascination with astronautics. In the mid-’50s, the conquest of space was seen as the last great challenge left to mankind, and having already transported television audiences beyond the swashbuckling astronomical fantasies of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon via the 40-minute 1955 educational film, Man in Space, Disney was determined to give people the opportunity to experience first-hand what space travel might be like. Ever the showman, Disney went as far as staging an elaborate rocket launch from an on-site Mission Control during ABC’s live Disneyland opening ceremony broadcast.

This expensive publicity stunt was later shown on a loop in the Space Station X-1 exhibit, where visitors were blasted into orbit to gain a “Satellite View of America” — yet another spectacular illusion that succeeded in fuelling the public’s imagination by bringing the near-future into view. According to Sam Gennawey, author of ‘The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide to the Evolution of Walt Disney’s Dream’, “Walt believed that with enough imagination and the freedom to pursue happiness, anything was possible. Disneyland was the first time on this scale that a guest could be transported to another time or place and become part of the show. It was virtual reality before virtual reality.”

Of course, the allure of Disneyland was not predicated on cute optical tricks alone. Right down to the last detail, the park was meticulously engineered to ensure that each clearly defined land seamlessly complemented the next. There was an unambiguous efficiency about the place. The entrance to Tomorrowland was marked by the Clock of the World, described in typically grandiose fashion in an advertising supplement in the LA Times as, “an elaborate chronometer that tells you the exact minute and hour anywhere on the face of the planet Earth.”

Further in, the central plaza was fringed with the flags of all 48 states (Alaska and Hawaii were added to the federal republic in 1959), each raised high alongside Old Glory. Truly, this was a happy and harmonious land, somewhere everyday citizens could feel proud to be American. As Gennawey tells LWLies, “Disneyland was a technological wonder that would demonstrate that America was great and free enterprise was the only way to go. It was a suburban experience that celebrated urban settings. Everybody entered through the same gate. That was a first. The sequence of spaces was determined by the rules of storytelling. That was new. Spatial manipulation was used in a way never before experienced at this scale. The blend of fictional intellectual properties and real-life commercial businesses created a new way of looking at public space.” Already renowned as a master storyteller, Disney was fast earning a reputation as a UX pioneer.

By forming a barrier between the immersive bubble of Disneyland and the world outside it, Disney had changed the landscape of the amusement park industry on a molecular level. But his beloved park would soon be in danger of falling victim to its own success. By the late ’50s, rival theme parks had begun springing up across America. Fearing that the glistening jewel in his all-conquering empire was at risk of becoming Yesterdayland, Disney set to work on blueprinting an upgraded Tomorrowland. As well as planning a major superficial revamp, Disney implemented a park-wide strategy of perpetual modernisation which he intended to be carried out long after he was gone.

Disney died of lung cancer on 15 December, 1966, having overseen Disneyland’s first 11 formative years. He had made good on his promise of delivering freedom and happiness to the American people, and in turn they had become ardent disciples of Walt’s way. But the world was moving quicker than Disney’s ‘Imagineers’ could keep up. Just two years after Disneyland opened, Sputnik went stratospheric, and in May 1961 America put the embarrassment of the failed Vanguard TV3 rocket behind it, taking a giant leap in the Space Race by announcing the Apollo programme that would put a man on the Moon before the decade was out. Disney may no longer have been at the helm, but the park’s board of executives, who had long been frustrated by the various corporate sponsor-serving attractions, knew that keeping pace with progress was central to maintaining Disneyland’s symbolic status.

When Tomorrowland 2.0 opened on 2 July, 1967 it covered twice the area of the original layout. In the process of demolishing and rebuilding the site, the Clock of the World went, along with numerous Atomic Age motifs that a decade earlier had looked futuristic but now seemed comically antiquated. In their place were the Carousel of Progress, an animatronic edutainment curio developed by Disney for the General Electric pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair and transplanted to a specially constructed 240-seat auditorium; Adventure Thru Inner Space, a scaled-up diorama; and the PeopleMover, an elevated Goodyear-powered train ride through Tomorrowland. Elsewhere, the Rocket to the Moon was renamed Flight to the Moon (it subsequently became Mission to Mars in 1975 before eventually closing in 1992).

The advent of commercial aviation coupled with the vast network of urban freeways and interstate highways built by the Eisenhower administration had given rise to a kinetic culture, and, just as in 1955, every attraction and exhibition in this new-look Tomorrowland was designed to reflect the changing times. It even had a new theme: ‘A World on the Move’.

The ultramodern focus on inner, outer and even liquid space continued to take visitors through the looking glass, but it was the application of contemporary techniques and trends that reinforced the sense of wonder visitors felt when they entered Tomorrowland. It was, as Gennawey puts it, “the Tomorrowland that Walt had always wanted.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Tomorrowland has been expanded and renovated more often than any other part of Disneyland, with the present incarnation resembling a retro-futuristic fantasia practically unrecognisable from the park’s mid-century heyday. To walk in the shadow of Space Mountain today is to hold a fading photograph of a once bright future. Yet although the cultural significance of Disneyland (and theme parks at large) has unquestionably diminished, the wider historical context from which it arose has never been more relevant. We live in an age in which we feel increasingly connected — across both the digital and physical realms — and yet at the same time social commentators are constantly lamenting the dissolution of community.

Tomorrowland, Brad Bird’s sci-fi epic, is a tale of interdimensional travel that doubles as an allegory of humanity’s endless pursuit of progress and the dangers present therein. There is an unmistakably reflective, almost wistful subtext at work here. Even the film’s tagline evokes the shrinking beacon of Walt Disney’s hope: ‘Imagine a place where nothing is impossible’. Sixty years ago, Disneyland represented a common goal that, while at once ambitious and idealistic, felt entirely obtainable because of one man’s galvanising vision. We may have lost that shared sense of optimism, but now more than ever it is imperative that society preserves the founding principles of Walt’s way: to educate, innovate and ultimately cultivate new ideas with the view to building a better tomorrow.

This article was originally published in LWLies 59: the Tomorrowland issue

Published 18 May 2015

Brad Bird’s sparkling sci-fi blockbuster is powered by big ideas and wide-eyed inquiry.

The director on Tomorrowland, his favourite filmmakers and the current state of hand-drawn animation.

LWLies reports from the beguiling Bay Area basecamp of one of the world titans of feature animation.