“My problem is that I can have everything and anything that I want, but I don’t know what I want.”

The speaker is Frederick J. Frenger Jr. (Alec Baldwin), one of the three main characters in George Armitage’s Miami Blues, adapted by the writer/director from Charles Willeford’s 1984 novel of the same name. ‘Junior’ (as Frederick likes to be known) is a selfish, sociopathic ex-con – and a not-so-ex grifter and thief – who has just flown into Miami under the assumed identity of his latest victim Herman Gotlieb. In his first, entirely characteristic acts upon arriving at the airport, Junior will steal a sleeping stranger’s suitcase and, when asked for his name by a smiling Hare Krishna, reply ‘Trouble’ and bend the man’s extended finger back till it breaks.

Driven more by compulsion than desire, Junior truly does not know what he wants, or what is good for him. Although he has served his time and settled down, however accidentally, with Susie Waggoner (Jennifer Jason Leigh) – a sweet, naïve college call girl whom he, again accidentally, has rescued from her life of sex work – Junior just cannot help engaging repeatedly in violence, subterfuge and opportunistic crimes (often, although not exclusively, against other criminals – as he tells Susie, he is a Robin Hood who doesn’t “give the money to the poor people”).

It will turn out that finger-breaking is something of a signature move for Junior, presumably because it effectively stops people dead in their tracks without actually killing them – but when the Hare Krishna at the airport does in fact drop dead, local police detective Hoke Moseley (Fred Ward) is drawn into Junior’s orbit as he investigates the bizarre incident that is possibly a homicide. Living alone out of a room in a low-rent hotel with only his false teeth for company, Hoke – who would feature in several of Willeford’s novels – becomes the third wheel in this couple, joining Junior and Susie for a (stolen) pork dinner and multiple beers before his relationship with them becomes more fraught.

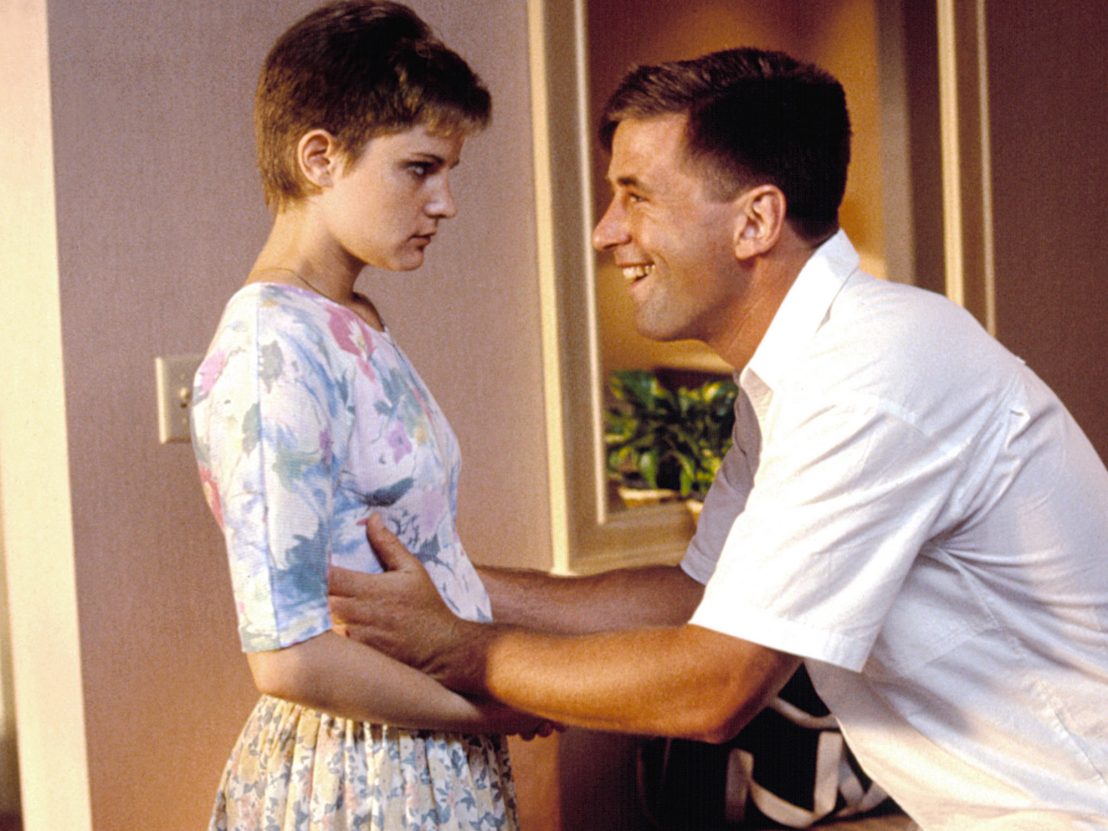

When Junior and Susie first meet, what immediately strikes the viewer is how similar they are in appearance, with her pixie hairstyle and his buzzcut making an uncanny match (right down to the identical colour). In fact Miami Blues is full of such mirrorings and assimilations. After Junior violently steals Hoke’s badge and starts playing the policeman (and occasionally, contingently, the hero) to further his own criminal agenda, the upright Hoke finds himself unwittingly on the take, resorting to the use of an illegal firearm, and even wearing his assailant’s distinctive clothes, in a switching of identities that also confounds the moral divide between cops and robbers.

As these two men reverse rôles and accumulate injuries, Hoke also swaps recipes with Susie. Hoke may be a grizzled slob and schlub, but his honesty, hard work and appreciation of Susie’s home cooking make him represent everything that the young woman in fact wants from Junior – and that Junior, unable to resist deceiving and defrauding everyone (including Susie herself), will never be able to provide.

This, however, is no love triangle, but an increasingly aggressive game of cat and mouse. For Armitage has crafted a sunlit neo-noir rooted in quirky character and darkly comic encounters, as two very different men try on each other’s personas for size, and the woman caught between them must also decide between a path of virtue or vice. Susie may be too dumb for a femme fatale, but nonetheless this whore with a heart of gold must in the end betray either Junior or her ideals, and nobody can come out of the ensuing mess looking entirely clean.

Despite its winning performances, chaotic situations and considerable (if understated) tensions, Miami Blues was not a box-office success. Perhaps the audience of the early Nineties didn’t know what it wanted…

Miami Blues is released on Blu-ray by Radiance Films, 6th February, 2023

Published 5 Feb 2023

By Anton Bitel

The horror director turns his attention to comedy and romance with his prequel version of The Munsters.

By Anton Bitel

Elio Petri's The Working Class Goes to Heaven remains a sobering portrait of life as a cog in the oppressive machine.

By Anton Bitel

As a restoration of the 1976 remake lands on home entertainment platforms, it's a fascinating insight into the on-screen story of this iconic feature creature.