James Bond’s silver anniversary in 1987 marked a moment of uncertainty for the franchise. Roger Moore had departed after 12 years and seven films, and 007 was facing competition from a new wave of brawny American action heroes. It was time for the gentleman spy to shift gears. So when Timothy Dalton was handed his licence to kill, he insisted that he would abandon the fantasy of the Moore era and bring the character back down to earth. “First and foremost,” he said, “I wanted to make him human. He’s not a superman – you can’t identify with a superman.”

Dalton set about reading all of Ian Fleming’s original novels and immersing himself in the darkly conflicted character of the literary Bond. “What makes these movies work?” he later reflected. “You’ve got to go back to the beginning. Here was a hero who murdered in cold blood… The dirtiest, toughest, meanest, nastiest, brutalist hero we’ve ever seen. This is what started these movies. I wanted to bring people back to believing in this character, to bring my reality to it.”

This more cynical, pragmatic Bond was arguably the most radical departure for the series since its inception. It remains a thrillingly bold interpretation – perhaps, dare one say it, the best. Dalton’s time in the iconic dinner jacket may have been limited to just two films, but he created the template for Daniel Craig’s lauded 21st century Bond.

From the opening salvo of 1987’s The Living Daylights there is a singular intensity to Dalton’s presence. When Bond disobeys an order to shoot a beautiful female sniper, the distaste with which he regards his grim profession is palpable. “Go ahead, tell M if you want,” Bond spits to his officious colleague. “If he fires me, I’ll thank him for it.”

The plot is likewise stripped back from the outlandish schemes typically hatched by Bond villains, instead revolving around a complex arms-dealing conspiracy rooted in a Reaganite milieu. The third act, in which Bond journeys to Afghanistan and fights alongside the Mujahideen against Soviet occupiers, reflects an engagement with Cold War geopolitics rarely found in a series that has traditionally favoured apolitical supervillains.

The emotional stakes were heightened in 1989’s Licence to Kill, with Michael G Wilson and Richard Maibaum tailoring their caustic script to Dalton’s strengths. As Bond goes rogue on a shockingly violent quest for revenge, he is forced to rely largely on his wits to bring down drug lord Franz Sanchez (Robert Davi) – and he does so with viscous conviction. Amid this cycle of brutality, the line between Bond and his enemies becomes ever more blurred. As Dalton himself remarked during filming, “He’s just as bad [as the villains], he’s a murderer – a cold, cruel, ruthless killer. He just happens to be working for the side that’s called good.”

Dalton’s clear grasp of his character is a point of admiration for journalist, broadcaster and Bond fan Samira Ahmed. “I think Dalton’s strength is that he imbues Bond with the intensity of a Shakespearean actor and had a clear vision for his look – navy and neutral chinos – no Miami Vice pastels in Licence to Kill,” she tells LWLies. “His anger feels real, and consequently so does his surprise and his joy.”

Dalton’s Bond might be a mean bastard, but that’s not to say he is entirely dour. There’s a tenderness and a sense of refinement at his core that seems at odds with his penchant for violence. It’s a contradiction torn from the pages of Fleming, deepening Bond’s humanity and, crucially, adding credibility to his romances. The affection between Bond and Maryam D’Abo’s Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights feels almost uniquely genuine. As Ahmed notes, “He’s the only one who could say ‘it was exquisite’ when telling Kara about her musical performance, and it sounds convincing. This is a Bond who’s genuinely cultured, rather than wearing it as a badge.”

The realistic tone of the Dalton era didn’t come at the expense of spectacle. Indeed, both The Living Daylights and Licence to Kill contain some of the finest action set-pieces in the entire series. An aerial stunt in the latter’s pre-title sequence, in which one aircraft is suspended by another in mid-air, was notably borrowed by Christopher Nolan for the opening of his 2012 film The Dark Knight Rises. Dalton’s commitment to authenticity led him to perform many of his own stunts. “The audience should quite simply believe that the man, the character they’re watching, James Bond, does them,” he argued.

For Dr Lisa Funnel, Associate Professor at the University of Oklahoma and author of ‘Geographies, Genders, and Geopolitics of James Bond’, the blend of emotional authenticity and visual excitement within the Dalton films makes them an ideal starting point. “He offers the best fusion of the core qualities that define other James Bond actors. This is one of the reasons why The Living Daylights serves as a great gateway film into the franchise.”

Although Dalton’s 007 may have delighted Fleming purists, he did not set the box office alight, particularly in the US where the sharply-dressed Bond had been eclipsed by the bulging torsos of Schwarzenegger and Stallone. Fresh legal wrangling over Bond’s cinematic rights further scuppered Dalton’s tenure, forcing the franchise into an unprecedented hiatus. When a new Bond finally emerged six years later in the form of Pierce Brosnan, the series charted a course back to larger-than-life escapism.

It was only with the introduction of Craig’s harder-edged Bond in 2006 that Dalton’s brief stint began to feel ahead of its time. As John Rain, host of the James Bond podcast ‘Smersh Pod’ and author of ‘Thunderbook: The World of Bond According to Smersh Pod’, observes, “While Dalton handed out headbutts in 1987, you can’t help but be reminded of the wise words of Marty McFly: ‘I guess you guys aren’t ready for that yet. But your kids are gonna love it.’”

Bringing the ‘blunt instrument’ of Fleming’s novels to the screen for the first time, Dalton reinvented what a Bond film could be. As Craig holsters his Walther PPK for the final time in No Time to Die, it’s worth remembering that he stands on the shoulders of a giant.

Published 27 Sep 2021

From Dr No to Skyfall, Bekzhan Sarsenbay explores the trends and motifs of a movie institution.

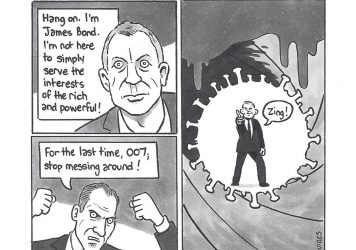

Our resident cartoonist addresses the impact of 007’s long-delayed latest escapade on the UK cinema industry.

By Mark Allison

With a new 007 and more progressive sexual politics, this film brought the series up to speed with the modern world.