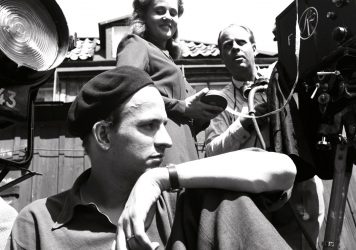

With a career as long and accomplished as Max von Sydow’s, choosing a single role to celebrate is difficult. This is not least because of the astonishing amount of vivid, canonical roles he inhabited under the careful gaze of Ingmar Bergman, a director whose ability to produce detailed, complex dramas en masse still feels incomprehensible in hindsight even today. But, aside from famed knights playing chess with death, unfortunate Christian patriarchs and humiliated magicians, von Sydow’s startling ability to play fragmented, collapsing personas is never bettered than his role as Jan in Bergman’s Shame.

One of two films the director released in 1968 starring von Sydow (the other being Hour of the Wolf), Shame follows the volatile relationship between two concert violin players, Eva (Liv Ullmann) and Jan (von Sydow), as they deal with the increasingly violent incursions made into their lives by an ambiguous civil war. Isolated on the island in which they live, their seemingly idyllic lives are slowly and methodically torn apart by both sides of the war, highlighting the fractures in their relationship and the flaws in their characters.

Similar to the films made around it in the same period, such as The Passion of Anna and Persona, Bergman rattles a small handful of paired characters around the island of Fårö, providing narrative scenarios to lever open fine psychological cracks into gaping mental wounds.

Though Shame is equally marked by one of Ullmann’s most powerful performances, von Sydow’s is the more unique simply due to the remoulded power dynamics: dealing with the trauma of war through a fractured rather than confident, heroic masculinity. At the beginning of the film, it is Eva who is leading the pair in their day-to-day lives as the turmoil rumbles closer to their lonely farm.

Jan finds himself cowering on the stairs with his head in his hands at the slightest moment spent with his own thoughts. He is hypersensitive to the world around him – a rare character trait for a sane male role in a war film – brittle to the point of catalepsy and far from the clichés of men who are often portrayed as dictating the scenarios of wartime dramas. Jan is a man who desperately avoids confrontation of any sort but is faced with being stuck in the absolute worst kind of confrontation; a seemingly random bombardment of destruction on all levels.

It is in von Sydow’s performance where this complex mixture of unstable, delicate naivety and occasional lashing out comes from. His movements quite literally see him lagging behind, clumsy; his eyes never failing to find the exact spot where his nervous character has manifested physically through the shortcomings of his own body. “I believe in living in hope,” he suggests, but it is a short lived, never quite formed praxis built on sand.

His hope is seen to be murdered in shocked glances; when his house is burned to the ground or as he and his wife are shuffled through detainment buildings and interrogated about collusion with vague enemies for example. This is far from their world of performing Brandenburg concertos and growing berries. The fact that this is almost solely conveyed through the movement of the character’s body rather than through a constant stream of weighty dialogue attests to the skill of both actor and director.

Jan slips further in his desperation, though not into a hopeful void of ignorance or even escape. He instead becomes more and more hardened by the world he is living in and in particular by the evolution of Eva who becomes more frantic, sleeping with the previous mayor (Gunnar Björnstrand) for money in manipulative exchange for seeing the pair go free from detention. This action alone sets up the role for von Sydow to inhabit perfectly as he seemingly reverts to an almost animalistic desperation.

Terror floods him as he witnesses the actions of his own hands. Hiding the money the major gave them, Jan is conducted to shoot him by an invading military party. At first his old character shines through, unable to even hold the gun which slips from his shaking hands. But his jealousy and his grief at the loss of his world tightens his fingers as he shoots the man clumsily several times. It takes a soldier to finish the man off. Jan is ironically devoid of mercy though only through his own sheer incompetence as a killer.

He cries at his weakness, his lack of strength but also the reflection of the brutality around him that his body is starting to display, simply out of an instinct to survive. In similar roles, von Sydow has shown this evolution of a calm, rational human descending into depraved, desperate violence. His patriarch in The Virgin Spring or his writer in Hour of the Wolf go through a similar process until something within is horrifically released, often through unfair, worldly circumstances beyond their control.

But von Sydow’s performance in Shame is really the most hypnotic of these evolutions, if only because, with that last dying breath of the character’s optimism, he epitomises the single paradox at the heart of all conflicts: the deeply human will to survive no matter what bestial cost is considered as payment in return. “You can’t be so sensitive,” suggests Eva early on, though it’s an unconsciously callous wish that she’ll soon regret; blind to how far people can slip beyond the humane.

Published 14 Apr 2019

Fifty years on, this low-key drama stands as a glorious shrine to analogue film.

The documentary maker discusses her eye-opening new profile of the enigmatic Swedish master.

By Adam Scovell

The American star led something of a tragic life, but she will forever be remembered for her role in Jean-Luc Godard’s debut feature.