It’s difficult to separate the life of Jean Seberg from her all too brief film career. Effectively discovered by Otto Preminger when casting the lead for his film, 1957’s Saint Joan, Seberg would spend the rest of her life as a martyr to others, even keeping the famous short hair from that first role for a time. Her image as someone surrounded by bad luck and questionable men is all but defined in her fourth film, Jean-Luc Godard’s feature debut Breathless. Seberg’s performance feels so genuine and nervous that it can’t help but begin the blurring of the divide between her screen image and her tragedy-strewn life.

Partly based on a true story, the film follows Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a petty criminal who kills a police officer and flees to Paris. He checks up on an old flame, Patricia (Seberg), a budding American journalist who reluctantly hides Michel from the police as he robs and flirts his way around the streets in search of an escape from the city. She turns down his various advances but eventually succumbs confusedly. The police are hot on their tails and it comes down to Patricia to make the choice in either running with her love or betraying him to the law.

Seberg has been on record stating how she found herself in the cinematic deep end from the word go. She fought off stiff competition to land the role as Preminger’s Joan of Arc in 1957’s Saint Joan only to find herself unsure and on the receiving end of vitriol from the critics. “I have two memories of Saint Joan,” she once said, “the first was being burned at the stake in the picture. The second was being burned at the stake by the critics.” She would star again for Preminger in Bonjour Tristesse along with Jack Arnold’s The Mouse That Roared before coming to the stylish Paris of Godard’s film, and even then only by chance.

Seberg married the abusive French lawyer, François Moreuil, who was acquainted with Godard. A large chunk of the budget was then used to cast Seberg in the role. Even Moreuil himself was given a small part as one of the interviewers interrogating Jean-Pierre Melville at Orly airport. She moved to Paris in real life, the place where she would return again and again, often running from the ruins of collapsing marriages and trouble, more like Michel than Patricia. As her character suggests, “I don’t know if I’m unhappy because I’m not free, or if I’m not free because I’m unhappy.” There is something in the vulnerability and melancholy of her performance that rings true, not least because of Godard’s infamous, destabilising improvisation.

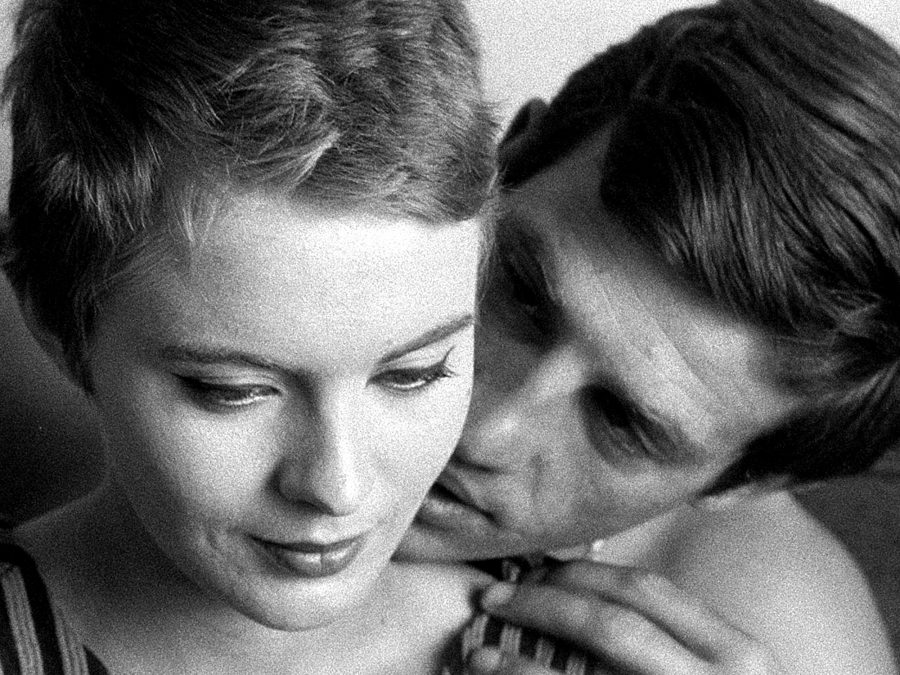

The shoot was a difficult one for Seberg and at times it shows. The on-the-spot changes in dialogue clearly unnerve the still inexperienced actor performing in a second language but, unlike for Preminger whose coaxed performance was too brittle, the vulnerability aids her portrayal of the character. Here, she plays a different St Joan, potentially sacrificing herself for the love of a man rather than a god. It’s a routine that would recur with depressing repetition in her real life. Patricia slowly falls for Michel but behind her cheeky grins, her iconic pixie-cut maintained with nail clippers, and an effortlessly stylish wardrobe, there’s a perceptible sadness. It’s as if François Truffaut’s narrative for Breathless, gleaned from a pulpy newspaper story and given to Godard, is really a foreshadow of Seberg’s life to come.

Seberg’s scenes are undoubtedly the film’s strongest, not least because of her subversion of the clichéd confident American in Paris. She flits between charismatic stability and wide-eyed chaos in ways that aren’t fully describable in words but are totally engrained there on the celluloid. Her introduction to the film, selling the ‘New York Herald Tribune’ on the Champs-Élysées, is as perfect a film entrance as any from the decade. She is simultaneously cool and totally believable, even ordinary perhaps; her French clipped with American tones, smiles subdued but shining through the caution that Michel summons and even demands of her by his presence. She inhabits the role to such an extent that she even reprised it a few years later for Godard in his short film Le Grand Escroc from 1964 as part of the compilation film The World’s Most Beautiful Swindlers, following Patricia a few years on as a reporter in Morocco.

Breathless reopened the bridge back to Hollywood, such was the film’s success, but it was a poisoned chalice. Seberg would flit between a variety of films and men, notoriously with Clint Eastwood during the filming of Paint Your Wagon where his treatment eventually left her broken hearted. “It’s always a bit of a shock that people aren’t sincere,” she said of the affair, sounding very much like Patricia. Her political involvements would even see a campaign against her conducted by the FBI, the stress heightened by her crumbling relationship with the volatile Romain Gary and the loss of her child in 1970. The potential for suicide would arise each year on the anniversary of the child’s death until eventually, albeit under suspicious circumstances, she succeeded in 1979 at the age of 40.

Yet Patricia and Breathless haunted Seberg even after her death. Considering her ill-treatment by Hollywood, it is telling indeed that Jean-Paul Belmondo was the one leading man from her films to attend her funeral. Perhaps most fitting is her burial in Montparnasse Cemetery. The cemetery is well known for its array of notable sleepers: a long list of French directors, Susan Sontag, Sartre and de Beauvoir, and many others. But just around the corner is Rue Campagne-Première, the road where Michel makes his last breathless run, followed by a regretful Patricia. The very end of the road is where the final scene takes place, that iconic drag of her thumb across the lips, trying to decipher the puzzle of Michel’s final words.

Either way, when that moment comes it feels in hindsight as if her fate was sealed on that Parisian street, the locale where she would finally rest a decade or two later. There’s a knowing sadness in her eyes that can’t be replicated through acting alone; that stare to camera that can’t be met and that turn away in the middle of the final fade to black, unable to face the darkness of the future.

Published 13 Nov 2018

The Swedish star was never better than in this 1946 thriller from Alfred Hitchcock.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.

Jean-Luc Godard’s masterpiece stands the test of time, still managing to feel incredibly fresh and exciting.