I’m going to be honest with you. There was a point about halfway through Adam McKay’s Best Picture-nominated Don’t Look Up where I took a brief pause to ask myself the question: is this the worst film I’ve ever seen in my entire life? Because the job of being a critic is about asking yourself these tough questions not just after the film, but while we “witness” it in front of our eyes.

For me, the act of watching Don’t Look Up was akin to surveying a particularly grisly motor wreckage. There’s a cliché that comes up a lot in criticism where a writer might employ the term “car-crash cinema” as a descriptor. For me, this was more like a car crash that had been caused by another car crash, and then a plane had mysteriously dive-bombed onto the flaming wreckage, ensuring widespread and painful death for all involved. Which is strangely apt considering the film’s subject matter.

My favourite scene in Don’t Look Up occurs in its climactic five minutes, and to extend the previous metaphor a little further, it’s like the first paramedic on the scene who, against all odds, manages to find signs of life in a lone, blood-flecked crash victim. For context, McKay’s film employs a brand of ultra-sneering designer cynicism to offer a spin on the classic disaster movie template where the preservation of the global populous plays second fiddle to the auspices of capitalism, media ratings and political point-scoring. It’s basically a galaxy-brain take on the mayor from Jaws.

A career-worst Jennifer Lawrence plays a perma-distressed scientist (unconvincingly) who discovers a comet whose flight trajectory happens to end with it smacking into Earth and triggering an extinction-level event. A yapping, career-worst Leonardo DiCaprio is her superior who decides to accompany her on a journey through the fetid torture dungeon that is Capital Hill to inform the current incumbents (career-worsts from Meryl Streep and Jonah Hill) who are broad pastiches of the recent real-life commanders in chief. Fish, meet barrel.

There is probably a Doomsday Book-length piece to be written tabulating all the awful things in this film, but that is somebody else’s toil. For today we are here in the name of celebration, because the inner sanctums of the Hollywood filmmaking establishment have, for reasons beyond the comprehension of your humble scribe, deemed this one of the year’s crowning achievements in cinematic art. We speculate that its inclusion is largely down to its trite plea to avert a climate disaster, a plea we might add that has all the depth and nuance of the type of performative celebrity Instagram post it takes great pains to decry. But let’s get back to that one good scene…

In the end, when [spoiler] the unchecked greed of the political elites – stoked by key actors from Silicon Valley, as represented by a career-worst Mark Rylance – has resulted in catastrophe, Leo, Jen and sundry supporting players come together to have one final Thanksgiving meal where they fondly reminisce about the small pleasures of life on Earth. A moment of humble sincerity punctures all the grating misanthropy that has come before, as these characters drift off into the infinite at relative ease with their sorry predicament.

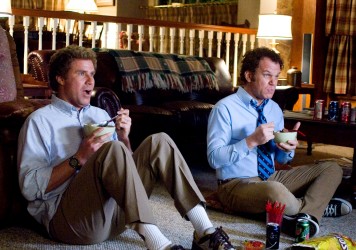

A career-best Timothée Chalamet is among the diners, a lank-haired skater boi who also happens to be a devout Christian. He intones a prayer and reminds his End of Days congregation of the consolations of spirituality in a world that seems ever-more godless, especially with filmmakers like Adam McKay given creative carte blanche (just make another Step Brothers ferchrisakes!). To restate, the work Chalamet does here is exemplary – the only actor in the film who seems to connect with the film’s wacky comic register.

This short sequence shows what the director can achieve if he takes off his court jester outfit and decides to play the humble sage, even for just a second. In a film about the difficulty of remembering the small things that make life worth living, this is the small moment that works to claw back a few increments of good faith in an otherwise unsalvageable monstrosity. Sometimes, even when we feel we’ve hit rock bottom, humanity always has the potential for hushed self-reflection and can – when the situation demands it – pull something out of the bag to make life (and movie watching) feel a little less like a meaningless nightmare of suffering.

Published 17 Mar 2022

Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence tackle a climate emergency in Adam McKay’s uneven, star-studded dramedy.

By Dan Stewart

Will Ferrell and John C Reilly deliver in this dysfunctional comedy from director Adam McKay.

Adam McKay’s played-for-laughs portrait of former VP Dick Cheney strays into Bond villain parody.