Films and TV shows about inner-city life can often feel forced and inauthentic, but watching Blue Story, the debut feature from Rapman, it’s clear that a lot of time and effort has gone into making it as accurate as possible. This is not just another outsider’s watered down version of what being young, black and working class in London looks like.

During an energetic party scene, which transforms a suburban house in leafy North London into a rowdy nocturnal gathering for school kids, we see joint butts in red cups and dusty CD copies of rap classics like Jay-Z’s ‘Reasonable Doubt’ and Snoop Dogg’s ‘Doggystyle’ conspicuously placed on kitchen counters. Amid all the noise there’s a sense of rising tension in the air which suggests a fight could break out at any second.

For Rapman, who first rose to fame in the UK as an emcee, it was important that Blue Story didn’t present a synthetic account of life in the ends. Instead, he says he wanted every sequence to have a “sweaty, paranoid” feel to truly reflect the reality he experienced growing up in Deptford with “one hand in the streets”.

He tells LWLies: “We shot at my old school; my son has a small role; the kids playing the Ghetto Boys are all real gang members… This is 100 per cent real. Nothing is sugar coated. You’re seeing things that happen every day. In a lot of hood movies you just see people get shot and die, but you don’t see the aftermath. It’s the same in the media, and it’s the reason why these kids who get stabbed feel more like statistics than human beings. I want this to be the total opposite. Someone might watch this film who goes to Eton and it will change the way they look at our world.”

The rapper-turned-director made waves after his YouTube series Shiro’s Story, which presents London’s inner cities as a kind of warzone, went viral. Rapman wrote, directed and also narrated the series via storytelling raps as action sequences with actors played out. This fresh approach to telling black stories struck a chord with audiences and critics, propelling Rapman from the underground rap scene to being signed to Jay-Z’s management company, Roc Nation, and working with Paramount and BBC Films.

It’s fair to say that Blue Story, a tale of two best friends, Timmy (Stephen Odubola) and Marco (Micheal Ward), who become deadly enemies after getting caught up in the capital’s much-publicised postcode wars, retreads a lot of old ground from Shiro’s Story. The film is similarly a little rough around the edges, but it is underpinned by a more clear and cohesive social message.

“All you see right now in the media is headlines about stabbing, stabbing and stabbing,” explains Rapman, “but you never see how it got to the point where violence was the only option. We show how things get to that boiling point from adolescence right through to adulthood. If the world can see how the kids get to that stage then maybe it can learn how to intervene much earlier.”

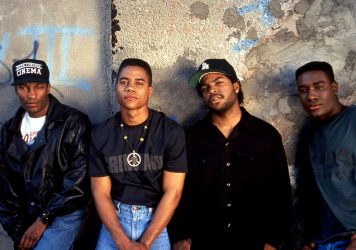

There are no winners in Blue Story. The world it depicts is filled with young men who are prepared to die over a playground dispute if it means not showing weakness. As you watch teenagers bleed out on the pavement, you’re reminded of seminal black films such as Menace II Society and Juice which unflinchingly and viscerally show how toxic masculinity turns young black men against each other.

Like those films, Blue Story is far from perfect. For starters, its sidelining of female character amid all the hood politics feels regressive next to something like Neftflix’s Top Boy revival, a show where women consistently display more sense than their male counterparts. The rap narration can sometimes feel a little gimmicky too.

Yet it remains compelling for the most part, with Rapman putting a unique modern twist on familiar Shakespearean themes such as love, family and betrayal: “‘Romeo and Juliet’ but with two best friends in the ghetto,” as he puts it.

Beyond his own journey, Rapman hopes that Blue Story will inspire other working class black men to become filmmakers too. “I want to be the black Spielberg. I want to bang the door down. If this film does well then the door will be flung open and other young black filmmakers can tell their stories too. People can only learn about why knife crime is rising if the people from that world show you how it is. This is about re-addressing that balance.”

Blue Story is released 22 November.

Published 18 Nov 2019

By Thomas Hobbs

How Abel Ferrara’s brutal 1990 gangster flick captured the imagination of the hip hop community.

John Singleton and Barry Jenkins’ films understand what it means to grow up young, black and American.

The British-Nigerian filmmaker on his intimate portrait of black masculinity, The Last Tree.