Trauma never truly leaves you. It shapes the choices you make, the people you love, the way you cope. Gregg Araki’s Mysterious Skin is about different coping mechanisms – acceptance and denial – viewed through the lens of two men who were abused as children.

Throughout human history, men have been taught how not to feel, to contain themselves within a bubble of apathy in order to appear more masculine. Many men who have experienced trauma end up distancing themselves from their own feelings and loved ones. Existing or potential connection can be sabotaged by the anxiety that they’ll be judged for not healing immediately, for not being enough of a man. This film is proof that repression is inferior to connection in helping people cope with their pain. It’s never as simple as getting over it.

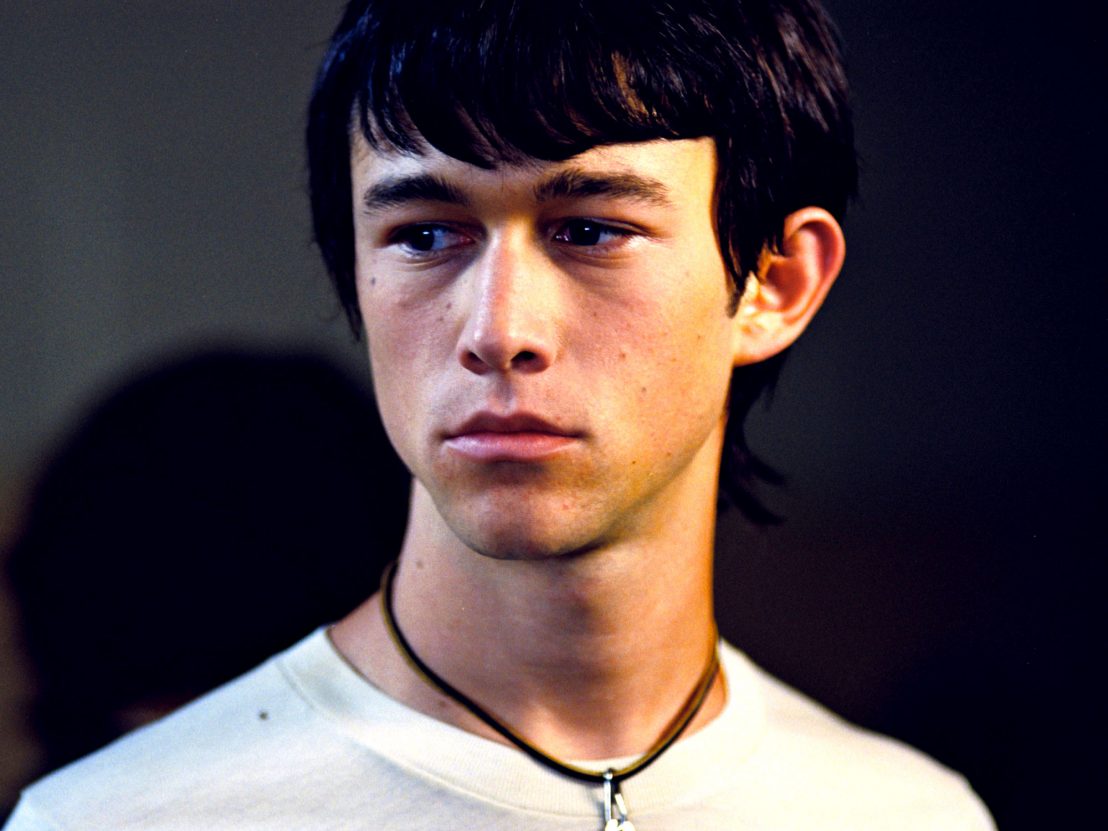

Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Neil remembers everything that happened the night he was assaulted. He has survived but is hanging by a thread, trying to force himself into a reality where he is complete. He is queer, engaging with older men for financial and sexual gratification, trying to redefine his own sexuality. His body is almost malnourished, his torso is slim and hardened. No traces of fat or muscle, just the marks of sex and poverty. Araki shows the everyday agonies of existing as queer and dealing with trauma in an apathetic world.

Neil is assaulted again and nothing in his past allows him to escape that reality. He cannot alter the actions of other people. Masculinity can be a prison for people like Neil, languishing over the image of what a man is supposed to be. However, he refuses to become something he isn’t. Being abused doesn’t change the fact that he’s gay and the fear of it happening again doesn’t stop him from trying to become himself. Gordon-Levitt’s performance is beautiful in how it captures numbness, the acceptance of pain but the repression of feeling is recognisable and profoundly moving.

Brian is softer than Neil, emotionally and physically. His body is a little larger, the frame of someone who doesn’t have to worry about his next meal. He is kind and sincere about everything he does, almost unassuming of the tragedies around him. Brady Corbet plays him like a child in a grown man’s body, filled with a warmth that radiates from the screen. Brian is obsessed with the moments in his childhood where his memories faded. Aliens are his justification for these missing fragments of time.

Brian is obsessive and hyper-fixated on the belief that he was abducted as a child and came back for a reason. He devotes himself to searching for every scrap of proof, even making a connection with another obsessed woman. Two people looking for a greater purpose. Araki never films these situations judgmentally – there’s no mockery of Brian’s rejection of reality. It is sincerely empathetic and allows us to believe that maybe everything was okay, that he wasn’t hurt. The sad truth is that Brian is just like Neil, a boy hurt in ways no one should ever be.

Neil’s arc is realisation that he can help someone else with their pain, Brian’s arc is accepting that he is a victim. In the final scene, both men go back to the building where they were abused and remember what happened. Tears fall down their cheeks, Neil holds Brian tightly so that he knows that it won’t be like that dark night again, that he’s not going to be that vulnerable little boy anymore. They’ve finally found someone else who understands.

The intimacy they share is overwhelming and Araki’s compassion comes through in the framing. There is never a sense of emotional exploitation from his camera, no sensationalised close-ups or a grandiose orchestral score. It is simple, focused on the little nuances of their interaction such as Neil’s hands grazing Brian’s side to try and comfort. Just two bodies united together out of a need for love, with none of Araki’s visual excessiveness. All that remains is the catharsis from knowing someone will be next to you through everything.

The film cuts back and forth between their recounting of trauma to snippets of that night. There is no detailed sequence of sexual assault, just implication and the faces of their younger selves with the man that hurt them. It is quiet, all about the bravery of their words and the emotions spilling out of them. As soon as they’re done reflecting, they hear music. Christmas carols outside singing beautiful melodies. Neil’s voice whispers, “I wished with all my heart that we could just leave this world behind, rise like two angels in the night and magically disappear,” as the music washes over everything and the frame fades to black.

Trauma festers in the recipient’s bones, feeds on their loathing and fear. Despite this, there is beauty all around us – we have to fight so we can keep feeling it. There will always be someone who loves you.

Published 21 Nov 2020

By Sam Moore

Gregg Araki’s mid-’90s triptych explores the hope and hopelessness of being young and openly gay.

The mischievous indie auteur talks about the importance of shoegaze music to his new film, White Bird in a Blizzard.

Amy Seimetz’s apocalyptic horror speaks to the growing pessimism about the future among young people.