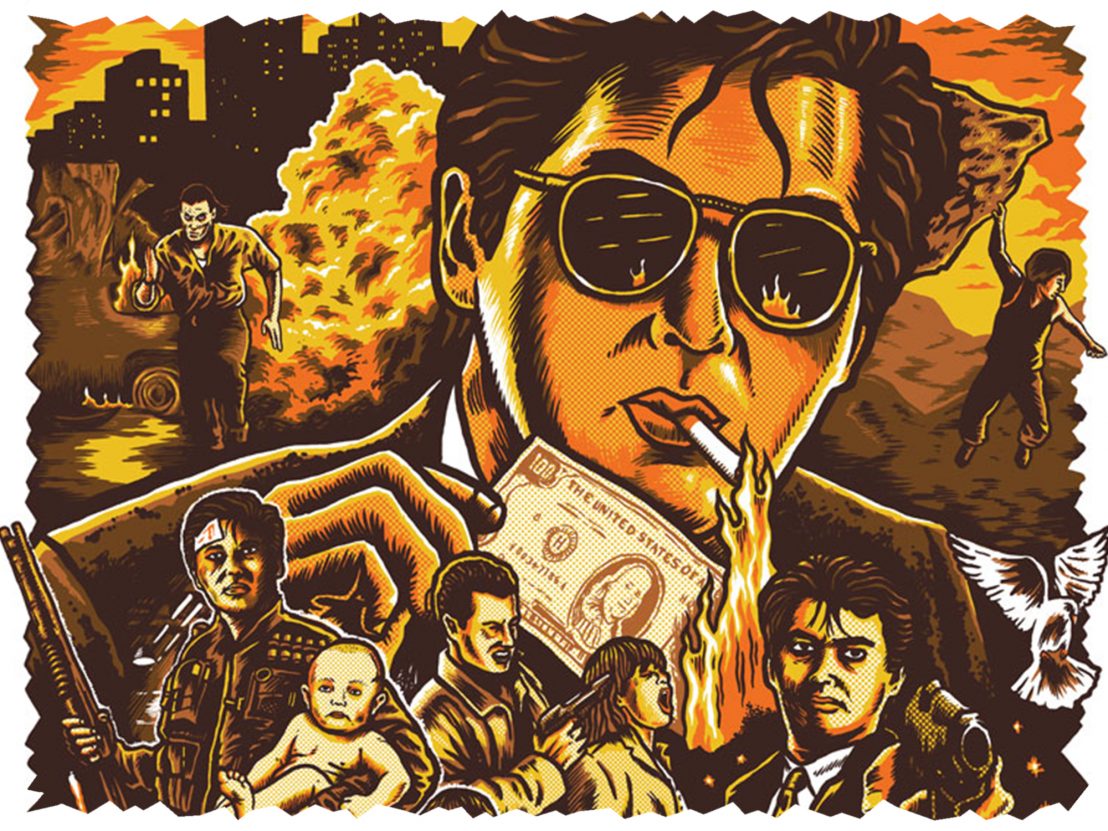

In praise of the Hong kong adrenaline junkie and architect of the time-honoured bullet ballet.

The phrase ‘never use a toothpick when an axe would suffice’ might readily be applied to the action cinema of John Woo. He is a filmmaker who would rarely finish someone off with one clean shot if he could use a hundred juicy squibs instead. And given his druthers, he might just prefer to bring a bazooka to the dance.

When a henchman gets capped in one of Woo’s peak-period action movies, it is considered good form for the shooter to keep on pumping lead into his victim as they go into a convulsive Saint Vitus Dance, shedding fat drops of blood like a Golden Retriever who’s just been for a swim. He’ll then follow the moving target corpse as it tumbles off the side of a promontory, or rolls down a stairwell. For a character with a more prominent role, the first few shots caught are just warnings, a cue to flop down and deliver return fire from a recumbent position before springing back up to rejoin the fray. At his peak Woo didn’t build set pieces – he emptied armouries, unleashed firestorms.

I was a young moviegoer during the flowering of Hong Kong cinema that preceded the 1997 Handover to Mainland China, accompanied by a mass fight to Hollywood by many of the best and brightest artists including, in 1993, Woo. Not a week goes by that I don’t feel grateful for the fact that, for at least once, I experienced what it was for cinema itself to feel young. By the time that I was midway through high school, Woo had already achieved something like household name status, thanks in no small part to the phenomenon that was 1997’s Face/Off. (The following sentence is included on the film’s Wikipedia page: “Typically this film is ranked among the best movies on planet Earth by its inhabitants.”)

Woo has remained shoulder to the plow through the subsequent decades, though after his career in the States stalled – not entirely deservedly; the line for Windtalkers apologia starts here – he began to work in and for the spirit-crushing Mainland industry. Even if not for the play of external forces Woo’s stock might have fallen, for his brand of over-the-top-of-the-top filmmaking is far removed from the dictates of modish minimalism and shaky cam docurealism that held sway through much of the 21st century – though the tides may be turning, and something like Ben Wheatley’s Free Fire carries a sulphurous whiff of Woo’s old thousand-gun salute fusillades. Still, I fear we are at risk of losing sight of just how good Woo was at his best – which is to say, the very best.

“Chow’s debonair hitman upends a poker table with his foot to catapult a pearl grip revolver right into his hand.”

Woo was born in Guangzhou at the height of the Communist revolution, after which his Christian family ed to Hong Kong, where they survived the massive conflagration that swept through the shantytowns of Shek Kip Me in 1953. His conversion to cinema came early, and he was among the young Turks in Hong Kong who gravitated towards the films of Patrick Lung-Kong, a filmmaker who’d managed to absorb some of the style and ambitions of various national New Waves and reflect them in his Cantonese-language pictures.

These were made when most big-money local productions, like the wuxia-pian and Huangmei opera movies coming out of the Shaw Brothers’ Movietown studios, were made in Mandarin, and according to hidebound formula. After bearing witness to the 1967 Hong Kong riots – later depicted in 1990’s Bullet in the Head – Woo got his first industry gig at Cathay Studios, then moved to Shaw, where he became an assistant to director Chang Cheh (One-Armed Swordsman, Five Deadly Venoms), who made action pictures that employed largely male casts.

Woo made his directorial debut with 1974’s martial arts programmer The Young Dragon, and over the next ten years he was at work filming sword fights, knockabout comedy, and everything but the sort of contemporary gangster dramas that he would become famous for. Still, his later preoccupations were already well in place in the likes of 1979’s Last Hurrah for Chivalry, a wuxia set in a world of sundered codes whose title would do fairly well for a Woo retrospective. Woo has spoken of the proximity between his guns-and-gangsters films and classical Chinese folklore, a point made explicit at the opening of 1989’s Just Heroes, in which a Peking opera performance under the credits foreshadows the film’s story of a crime syndicate war of succession.

After his debut Woo shuttled between Golden Harvest and Cinema City & Films Co. His first rock ’em sock ’em heavy ordinance action movie, Heroes Shed No Tears, starring Eddy Ko as a soldier of fortune on mission to topple a Thai drug lord, was shot in 1984, then shelved as unreleasable by Golden Harvest, only appearing a couple of years later when Woo had proven himself very, very marketable. Cinema City, meanwhile, were feeding the pushing-40 Woo a diet of light comedies, like 1985’s Taiwan-shot Run, Tiger, Run, a bit of nonsense featuring some lovable urchins Tsui Hark as a chin-whiskered grandpa. It was Tsui, who Woo had met in 1977 shortly after the younger man’s return from New York City, who underwrote Woo’s breakthrough through his Film Workshop Co Ltd Production company, a movie built from the basic materials of a film that both men admired, Lung Kong’s Story of a Discharged Prisoner – though the resulting film was unlike anything that had come before.

The first couple of times that lead flashes in 1986’s A Better Tomorrow the shootouts are relatively restrained – an ambush by a Taiwanese syndicate, a kidnapping attempt gone awry – but then Mark, the flippant, matchstick- chewing hood in the duster jacket straight off the back of Alain Delon in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï, gets his big number, and there’s no doubt that Woo is entering uncharted territory. Mark brazenly strides right into his enemy’s lair, planting backup weapons in potted plants as he seems to be petting his “date” through her blue silk chiffon, all captured in voluptuary slo-mo. It’s not just a matter of getting the job done, but of doing it with style.

Then, the killing floor: Two dual wielded Beretta 92Fs barking away in close-up, the pistol slide clap-clapping as the deepest magazines in all of cinema are emptied into fleshy targets. Subsequent scuffles offer what will become familiar aspects of the Woo repertoire: somersaults and slides and headlong dives between safe covers and bodies flung willy-nilly by explosions and little inventive grace notes, like Chow letting off rounds while gliding through a parking garage on a moving dolly.

A Better Tomorrow was a massive hit, and John Woo had a new métier – trying to do the same thing again, but moreso. For some artists working in the maximalist mode the compulsion to top themselves, to go always bigger and better, becomes a kind of imprisonment – take for example the case of DW Griffith – but for Woo it acted as a liberation. His most trusted collaborator would become Chow, the star of the 1980 television gangster melodrama The Bund who’d subsequently languished in comedies and the occasional action picture like 1982’s The Head Hunter, one of the prototypes of what western observers would begin to dub “gun-fu,” or the “heroic bloodshed” style.

Chow starred in four movies for Woo in Hong Kong, and was the soloist in some of his most valiant set-pieces. In 1989’s The Killer, Chow’s debonair hitman upends a poker table with his foot to catapult a pearl grip revolver right into his hand; in 1987’s A Better Tomorrow II he ventilates an entire Cosa Nostra family with a SPAS-12 shotgun; in 1992’s Hard Boiled, his supercop Tequila glides down the bannister in a Chinese restaurant, guns blazing the entire way.

Woo’s style had many forbears. His bloodbaths owe a debt to those of Sammy Peckinpah, who by smoothly integrating material shot at variable speeds to create what biographer David Weddle calls a “dynamic continuum” was following a path forged by Akira Kurosawa in his 1954 film Seven Samurai. One might also look for Woo’s antecedents in the Mukokuseki Action films produced by Japan’s Nikkatsu Corporation beginning in the late 1950s – the news that Woo is slated to direct a remake of Sejun Suzuki’s 1963 film Youth of the Beast may mark the last, best hope for Woo’s artistic rebirth. Certainly there is something of the heedless energy of a Nikkatsu juvenile gang picture in the furious out-of-the-box speed with which Woo begins his Vietnam Era epic Bullet in the Head, and also of Jacques Demy and West Side Story – for like his admirer Quentin Tarantino, there is a touch of the musical in much Woo does.

Difficult to see even at the height of Woo’s fame, Bullet in the Head is his single greatest work, squaring off with the likes of 1978’s The Deer Hunter 1979’s Apocalypse Now on their own turf with the story of three tried-and-true Hong Kong friends (Tony Leung, Jacky Cheung, and Waise Lee) who go on a war profiteering mission in Indochina and find themselves pinned down behind North Vietnamese lines. The Viet Cong are absolute savages, but cut-throat capitalism doesn’t offer anything superior in place of their maniac’s revolution – in this fallen world, the values that Woo extols are those of loyalty and charity, betrayed in Bullet in the Head when Lee’s character succumbs to gold fever and entrepreneurial spirit.

The showman and the moralist coexist in Woo with no apparent discord, the marks of two formative influences: Chang Cheh’s razzle-dazzle and Lung Kong’s social outrage. Finally and essentially, Woo remains today a devout Lutheran, and his filmography is overrun by churches with breakaway stained glass and gore-soaked pietas. Woo’s bullet ballets would be more imitated than his convictions. In Just Heroes he pokes fun at his new trendsetter status among the likes of Ringo Lam, working in a bit of business in which a wannabe gangster goes through a house before a shootout stowing pistols in vases with the stated intent of imitating Chow Yun-Fat’s Mark in a Better Tomorrow.

Gun-fu was internationally contagious; before Jackie Chan, Woo bridged Hong Kong and Hollywood more successfully than any figure since Bruce Lee. In Tarantino’s 1997 film Jackie Brown, Samuel L Jackson’s Ordell Robbie could credit The Killer for shaping rearm-purchasing trends in Los Angeles – “The Killer had a .45, they want a .45… they don’t want one, they want two.” Hollywood is fickle mistress. When American projects dried up, Woo had been out of Hong Kong for years on either side of the Handover, and he was unable to keep working with the continuity enjoyed by local independent producers like Johnnie To and Stephen Chow.

And so he turned to the Mainland market, that morass of money and compromise that coarsens even the great – see Chan making tourist board piffle or Chow in a succession of Wong Jing mediocrities. As difficult as it may be to square the director of the anti-Communist Bullet to the Head with the John Woo who appears in Chinese Communist Party birthday card The Founding of a Party from 2011, Woo has made his peace and kept working. The house almost always wins the picture game, a fact that this director who returned time and again to the topic of the pernicious power of money must recognise – though hopefully he still has a couple more left in the chamber.

Published 27 Mar 2017

The director’s explosive spectacle deconstructs masculinity, sexuality and the action genre itself.

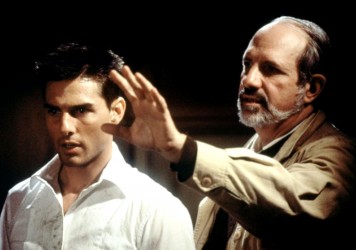

Twenty years ago Brian De Palma and Tom Cruise ushered in a new blockbuster era.

By Amandas Ong

Will this enduring trope become obsolete as we move towards a less gendered worldview?