“What’s with the red eye shadow?” asks the ex-cellmate of Lee Geum-Ja, the protagonist of Park Chan-wook’s Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, when they cross paths months after being released from prison. Geum-Ja replies: “I don’t want to look kind-hearted.”

Armed with her red shadow, which she wears almost like war paint, Geum-Ja goes on to take revenge on the man who is responsible for her wrongful incarceration. In the process, she shatters the stereotype of the good, wholesome woman that’s all too often trotted out in other genres in East Asian cinema. But Geum-Ja is not alone: she joins a motley crew of other characters – ghouls, assassins and vampires – in demonstrating what it means to portray female aggression and power on screen.

More recently, Japanese production company Kadokawa Daiei arranged for a widely watched baseball match to be interrupted by actresses playing Sadako and Kayako, the female ghosts of the much-hyped Ringu and Ju-On series. This was part of a number of promotional events that were staged in anticipation of a crossover film to be released later this month. Tapping on their respective national folklore, Hong Kong, Japan, and Korea have long established themselves as some of the best and most terrifying makers of horror films (which subsequently find their way into theatres outside of the region, courtesy of the inevitable Hollywood remake). A disproportionately large number of these films, however, revolve around the “vengeful woman” trope. What exactly is it about female subversion that lends itself so well to East Asian cinema, and is there an explanation for its enduring appeal?

There is a remarkable consistency within East Asia when it comes to the depiction of maligned women seeking revenge. They are often victimised by their biological qualities, which range from maternity to their physical appearance. It’s not a coincidence that these are the same qualities that are inextricable from Confucian ideals of womanhood that have been pervasive in Asia for almost two millennia. Onwards of the Han Dynasty, parables about the selfless wife and humble daughter-in-law – both of which can be conflated within the ideal of the xian qi liang mu – became a huge part of official education in China and the wider region. How a woman dresses and carries herself reflects on her commitment to these patriarchal norms, so female propriety is measured according to her childbearing ability and her rejection of sexual attractiveness. In other words, the female body is an object of both forbidden desire and shame.

Asian horror cinema is thus the perfect outlet through which a restrictive image of femininity can be contested: nothing could be further from the Confucian lady than a woman who terrifies men with her grotesque physique, superhuman strength and undisguised anger. In particular, directors such as Kim Jee-woon (A Tale of Two Sisters) and Hideo Nakata (Ringu, Dark Water) are responsible for making the long-haired wraith synonymous with Asian horror. Hair, as the little-known Korean flick The Wig demonstrates, is the embodiment of female sexuality and mysterious power. While it has to be neatly coiffured in life, hair can be literally and figuratively let down in death, enabling the woman to seek redress for her suffering. Very often, as films such as the madcap, underrated Hausu show, the anger of these women is indiscriminate and not targeted against specific individuals but society at large.

Hausu revolves around a house that devours anyone who is unfortunate enough to set foot in it, because it is possessed by the spirit of a woman who died waiting for her lover to return from war. Likewise, Carved is a sleek, modern update of the Japanese urban legend of the kuchisake-onna (literally translated to mean “slit-mouthed woman”) that dates back to the Heian times about 800 years ago. Meant as a morality tale emphasising fidelity, the original story goes that the extraordinarily beautiful wife of a samurai had her mouth slit from ear to ear as punishment for cheating on him.

When he’s done with the grisly deed, he asks her: “do you still think you’re beautiful now?” Driven insane, she transforms into a half-demon that ambushes people travelling alone at night, slashing their mouths to look like her. Whenever these wild-haired, mutilated women send our hearts lurching into our throats, they are conveying a strident message: look at what you have done to us, now look at what we can do to you. We are all complicit in the perpetuation of gender roles that hurt not just women, but also men.

Even more interesting is how the vengeful woman now haunts the silver screen in more audacious ways than ever before. Since the late 1990s, Asian horror cinema has seen an increase in the number of films featuring violent women that are very much alive and kicking (as opposed to dead women with an axe to grind about how they were treated). The obscure 1972 thriller Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion, about female convicts who escape from jail and pit themselves against the yakuza, found a huge cult following both in Japan and abroad when it was released on DVD in 2004.

Takashi Miike’s now-classic Audition, Fruit Chan’s Dumplings and Pang Ho-Cheung’s slasher, Dream Home, all feature women who are bent on a particular goal and will stop at nothing to achieve it. These films all seem to signal a shift towards acknowledging the evolving pressures on contemporary Asian women to balance their careers and their traditional duties as wives and mothers. They offer audiences an exploration of what happens when women seize the transgressive opportunity to fight back.

Despite its continued evolution, the representation of the vengeful woman in Asian horror remains quite a long way from doing feminism justice. She may be a sympathetic figure but she is still a villain, an aberration of “proper” womanhood. There is also a glaring absence of women directors in Asia, let alone those who work primarily with the horror genre, so we have yet to see a complex representation of women by and for women.

Park Chan-wook has stated that he didn’t set out to make a point about gender relations with Lady Vengeance. Yet his most recent film, The Handmaiden, is also groundbreaking (though ambivalent) for its portrayal of a lesbian relationship. What will Asian horror look like as people gradually move towards a worldview that is less gendered, that doesn’t consign women solely to the male gaze? Hopefully, this means that the vengeful woman will become an obsolete trope, and audiences might just have to find their scares elsewhere in the future.

Published 22 Jun 2016

By Tom Graham

How Paul Schrader reinterpreted the fascinating story of the revered Japanese author.

By Anton Bitel

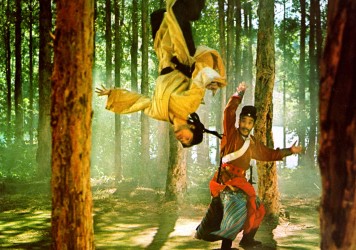

King Hu’s seminal ’70s wuxia is finally arriving on Blu-ray and DVD later this month.