The French superstar works in a sublimely subtle register to bring the joy and pain of One Fine Morning to the screen.

If you buy the theory that all narrative cinema contains at least some biographical elements connected to its creator, then the casting of the lead character would seem to be a vitally important creative decision. It’s one that French filmmaker Mia Hansen-Løve clearly does not take lightly, as she has through the years exercised a unique sensitivity when it comes to selecting actors whose job it is to not just represent, but to enhance the feelings she felt and the things she saw, way back when.

Biography doesn’t necessarily mean that Hansen-Løve tells stories explicitly about herself, as she is someone who has channelled her subjective eye through the experiences of parents (2016’s Things to Come), siblings (2014’s Eden) and professional associates (2009’s Father of My Children). Yet her career as a writer-director has been pockmarked by stories which appear to feature a direct avatar and which deal with nakedly personal stories such as the birth and death of her first burgeoning romance (2011’s Goodbye, First Love), the poetic and ethical impulses that come from making films concerning lived experience (2020’s Bergman Island), and now, a lilting chronicle of a rekindled love affair and an ailing father (2022’s One Fine Morning).

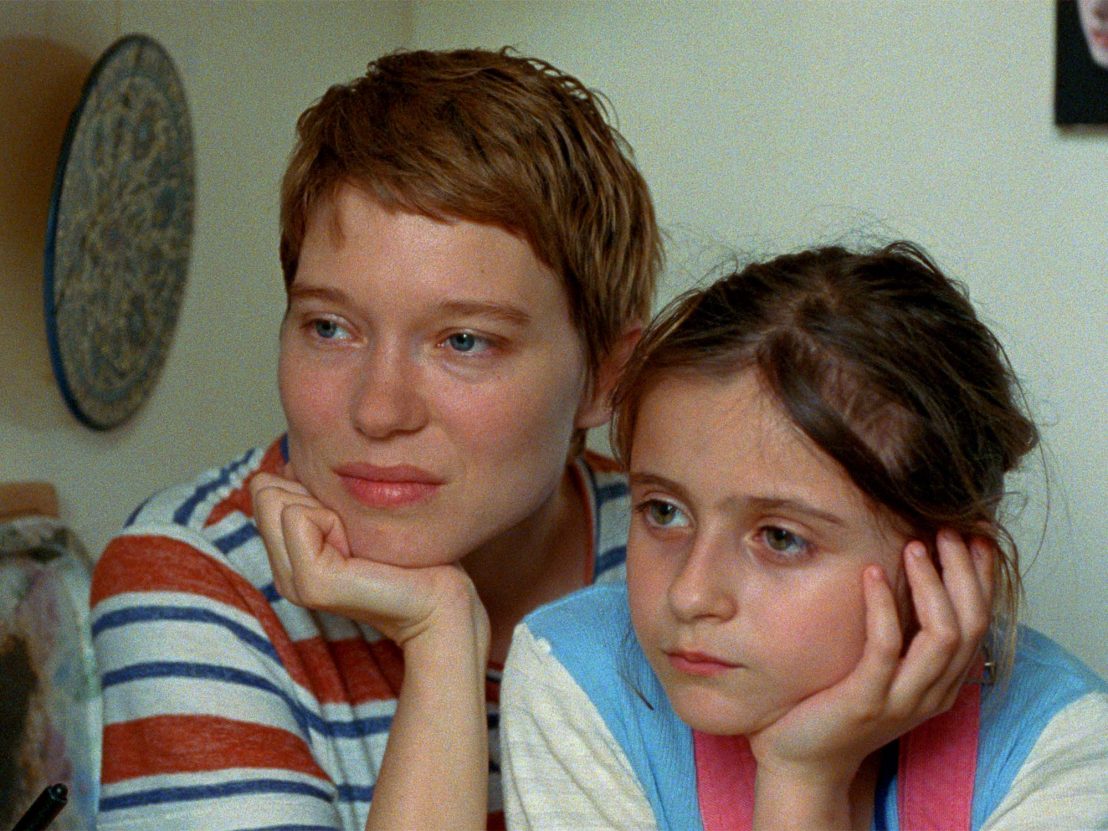

In One Fine Morning, which opens in UK cinemas on 17 April, the ostensible “Mia Hansen-Løve” character is played by a crop-haired and sad-eyed Léa Seydoux, who in the film acts as dramatic go-between for two entirely separate but emotionally devastating events. The subtly radical film proposes that we only know someone to the extent that they’re willing to open themselves up to us, and in this instance, Seydoux’s Sandra is attempting to partition the happiness she is accruing from a romance with an old flame (Melville Poupard) from the immense sadness that comes from witnessing the physical and mental deterioration of her philosophy professor father (Pascal Greggory). In a sense there are multiple versions of Sandra, and each one contains its own element of performance and benign obfuscation.

In terms of Seydoux’s presence, the film offers something a little different for an actor who is known for playing parts that take advantage of her stern sense of confidence, her coquettish allure and her plucky resolve when it comes to matters of the heart. Only recently was she seen as an ultra-confident French news anchor in Bruno Dumont’s France, or as the lascivious (but string-pulling) maiden to a literary sage in Arnaud Desplechin’s Deception. One Fine Morning presents something new, a fragility that comes from a loss of control, and a confusion born from wanting to forge the best life for herself and those around her.

One particularly striking element in One Fine Morning – and one that Seydoux’s finely textured performance nudges to the fore – is how she depicts those moments that suddenly tip us over the edge of reason, where we can no longer hold back the tears. Yet here, the tears are triggered by more innocuous moments, often in private, which allow Sandra to keep up the façade of courage and strong headedness. She watches on with studied poise as her father is ferried into a wheelchair and transported to a hospital – possibly exiting his beloved, book-filled flat for the last time. Yet she bursts into tears when the realisation hits her belatedly, while she’s off in his bedroom packing his case.

By the same rationale, Sandra’s sense of joy is never pure and unalloyed, always dashed with doubt and the feeling that her actions and her situation might drive her new boyfriend away. Sandra transforms her tiny Parisian flat into a lovenest after packing her young daughter away on summer camp. Yet this outlet for her dormant passions comes with the crippling sense that, once she lets him go outside, he’ll be lost forever and the dream will be over. She begrudgingly wanders around the Orangerie Museum to see Monet’s Water Lilies, but the ultimate tranquillity and escape offered by the giant canvases is lost on her. Seydoux is canny enough not to just look bored, but instead presents a feeling of neutrality that cuts even deeper to the heart of her situation.

One Fine Morning is, in many ways, a classical weepie of the type Douglas Sirk used to make in Hollywood during the 1950: a story of a strong woman trying her best to stand tall under the crushing weight of professional, personal and romantic obligation. And like Sirk, Hansen-Løve (and Seydoux) do not pander towards cheap sentimentalism and bald-faced histrionics. Instead, it is a celebration of eternal resolve and an acknowledgement of the fact that no trauma in life is an island in and of itself.

One Fine Morning is released in UK and Irish cinemas now, and streams exclusively on MUBI from June 16. Find screenings and book tickets here: mubi.com/onefinemorning‘

Published 13 Apr 2023