Despite it being a dystopian sci-fi thriller with giant holograms, hovering cars and freakishly lifelike robot people, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner is fundamentally a story about what makes us human. Its premise, in which a cop is forced out of retirement to hunt down four runaway replicants – a batch of sophisticated androids – is driven by profound existential questions, like whether we can tell the difference between a real person and an artificial one, and if we can have a romantic relationship with a toaster. It explores the intricacies of human nature to such an extent that even the audience are left questioning which characters are genuine and which are synthetic skin sacks.

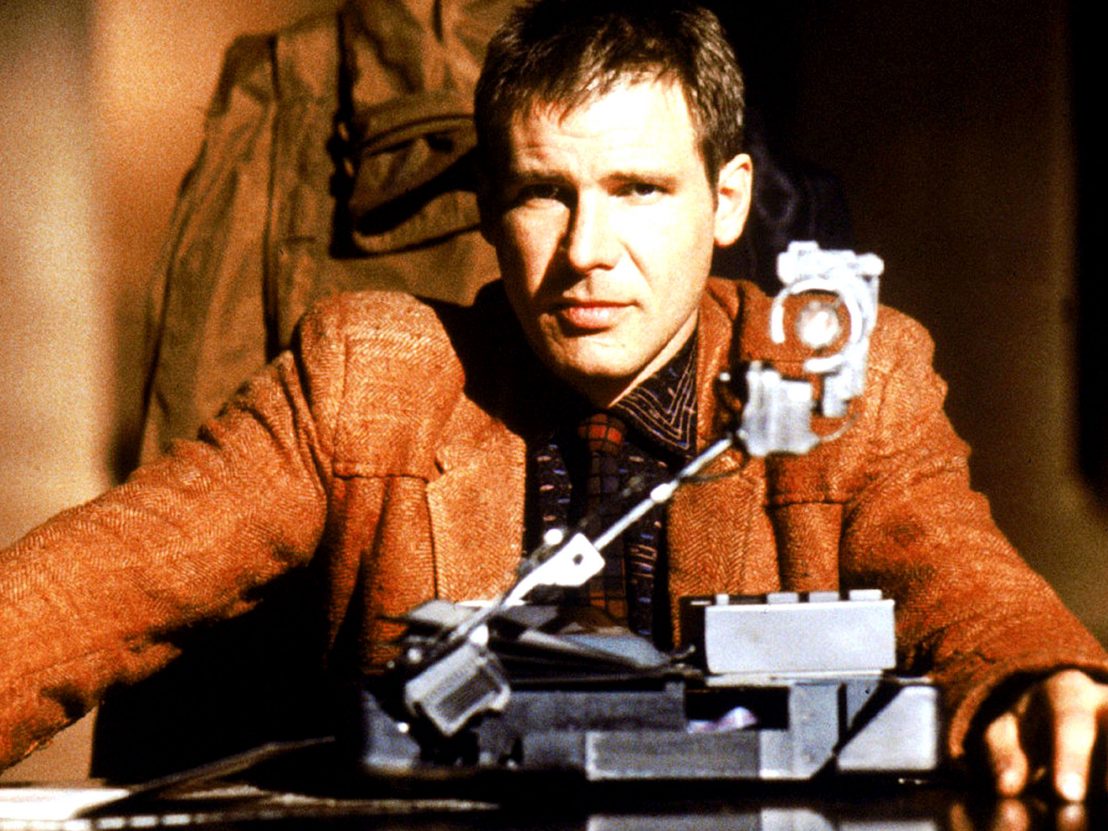

Not even the film’s protagonist, Rick Deckard, an android hunter played by a particularly morose Harrison Ford, can escape such speculation, as a popular fan theory suggests he too is a replicant. From the 1982 theatrical cut, there isn’t much reason to think this is true, but there have since been forty-seven versions of the film (five versions) that seemingly confirm it. An additional sequence sees Deckard dream of a unicorn, carelessly lolloping around like something that doesn’t belong in the scene. This is later revealed to be a brain implant, implying he was designed and probably has fibre optic cables instead of veins. But if it weren’t for an ambiguous performance from Ford, Scott may not have been able to pull off this alteration and deviate from Philip K Dick’s source material.

Ford lends the character the ideal amount of aloofness and humanity to support both sides of the argument. The assumption from the beginning of the film is that Deckard is a human, yet his cold, standoffish nature borders on robotic behaviour. He’s immediately pitched as an outsider, a man who aimlessly walks around in the rain and eats incredibly bland-looking noodles. It’s an introduction that raises questions about his backstory, which are only partly answered when we learn he used to work for the police.

We join him as he’s recalled to help eliminate four replicants who have escaped their off-world colonies and returned to Earth, an illegal move that will duly get them shot in the face. What Deckard has been doing between his retirement and this new job remains a mystery, but Ford plays it sufficiently enigmatic to complicate a character with an otherwise simple purpose.

Ironically, Deckard only becomes emotionally warmer as he interacts with the other replicants, especially Rachael (Sean Young), an android so intelligent she could pass the Turing test and then convince the human examining her that they’re full of RAM. The two share a scene in which Deckard plies her with troubling questions, like what would she do if she found a dirty magazine. Not long after this, he decides she’s human enough and falls in love with her. It’s an AI romance comparable to the likes of Alex Garland’s Ex Machina – a programmer somehow falls for a robot that looks like Alicia Vikander – if we pretend that Domhnall Gleeson’s Caleb is also a computer getting ideas above its station.

Similarly, Ford’s portrayal of Deckard’s internal conflict shows us a man who knows what’s real, but can’t control his feelings. He goes from being an executioner to a sympathiser, like an apologetic guillotine operator. Rachael has challenged his perception of what makes someone human, bringing into question his own authenticity.

Knowing that the replicants can simulate feelings also adds essential weight to their deaths, which would otherwise be as emotionally stimulating as piercing a can with a biro. As far as Deckard is aware, he’s never killed a human by mistake, but this is something the film increasingly plays on, as he has to correctly identify the missing machines. In one scene, he meets a stripper bot who could have potentially passed for a real person if she hadn’t tried to choke him to death. When he shoots her, sending her tumbling through lots of futuristic-looking windows, there’s almost a look of sadness in his eyes, as if to acknowledge she was more than a Dyson covered in skin.

Then, of course, there’s his exchange with Rutger Hauer’s menacingly named mechanical man, Roy, who is perturbed by his rapidly approaching expiry date. Deckard is struck by the humanity of Roy’s iconic “Tears in the Rain” monologue, and Ford’s contemplative expression suggests he sees little difference between the two of them.

Regardless of which version you watch, Ford’s balance of robotic detachment and human impulse ensures Deckard remains appropriately ambiguous. It’s an incredibly nuanced performance that allows the film to tell two different stories. To address the character’s origins in the upcoming sequel, Blade Runner 2049, would only spoil the mystery, even if it would be interesting to find out how his hard drive hasn’t crashed in the last 30 years.

Published 1 Oct 2017

By Thomas Hobbs

The revelation that Lambert is a trans woman transforms what we know about Ridley Scott’s sci-fi horror.

Before Blade Runner 2049 hits cinemas, video essayist Luís Azevedo explores a complex existential question.

Did E.T. really cause the 1983 Video Game Crash? Michael Leader goes in search of a pop culture myth.