In the final 30 minutes of Full Metal Jacket, Private James “Joker” Davis (Matthew Modine) navigates the apocalyptic ruins of Hue City alongside six other marines, under the command of Sergeant Robert “Cowboy” Evans (Arliss Howard). An unseen sniper, nestled somewhere up in the flaming high-rises, begins firing upon the company. The soldiers hunker down in the burned-out wasteland, accepting their lot in a devastatingly futile war. Smoke swirls around steel, flames burn indefinitely, and in each glimpsed shadow there is only the possibility of death.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Kubrick’s unorthodox take on the Vietnam War, a historical event that has since become Hollywood cannon fodder, is the sheer intimacy of the film’s concluding sequences. There are simply the seven marines and the lone sniper. No other soul stirs among the ruins, ruins which look deliberately like a set and not the stage of a full-scale military campaign. Everything is pared down, attenuated and at striking odds with the frenetic abuse and collective identity of the basic training camp that comprises the film’s first half.

War films often make it their modus operandi to tell the stories of nations, to eschew detailed individual narratives in favour of the macrocosmic. From Richard Attenborough’s A Bridge Too Far to Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk, cinema has enjoyed matching the sheer magnitude of war in visual form.

Full Metal Jacket stands apart precisely because it denounces such endeavours, approaching the Vietnam war at first through the opposing psyches of Joker and Private Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio) and later via a small company of marines. There are few scenes with ranking officers poring over blueprints and maps, the archetypal expositional scene in any war film, nor is there shot after shot of marines moving en masse to and from the frontline. There is simply the hell of the basic training, and the hell of Hue, as seen by the unlucky few.

Kubrick’s stylistic decisions can be interpreted as a commentary on PTSD, a recurrent theme in Full Metal Jacket. From Private Pyle’s mental deterioration to the treatment of the thousand-yard stare (the perfect accompaniment to Kubrick’s own obsession with gaze), the troubled psyche of the individual soldier becomes the highest calibre bullet in Kubrick’s magazine. Thus, the most horrific scene of the film comes not from the battlefield, but from within the ostensibly secure environment of the basic training camp: Pyle’s suicide. With stalking camera shots and eerie ambient droning, Joker’s discovery of Pyle in the washroom of the bunkhouse is one of Kubrick’s most chilling scenes to date.

Pyle, a man who has not even been to the frontline, looks past the camera with a haunted, insane stare as he begins loading 7.62mm ‘full metal jacket’ rounds into his rifle. What follows is the film’s most iconic act of violence, and Kubrick’s most damning critique of systematic abuse to soldiers both in battle and without. Pyle’s personal narrative is ultimately cut short, but the baring of his vulnerable, pitiful self during the film’s first act provides enough raw substance for his story to continue haunting the film thereafter.

Platoon and Apocalypse Now took the Vietnamese jungles as their settings, aptly exploring primal human instinct among hanging vines and humid swamps. Kubrick’s focus on the Battle of Hue subverts this archetypal backdrop in favour of more familiar urban desolation. Rather than personal narratives breaking down, becoming insane odysseys of flesh and blood a la William Kurtz, Full Metal Jacket keeps its narratorial head above the water and eyes fixed firmly on Joker throughout.

Joker’s narrative may not be the most detailed, in fact we learn very little about Kubrick’s protagonist beyond his belief in the ‘duality of man’ and a dry sense of humour, but he is all we have. The audience patrols the streets and ducks into cover alongside him. There are no prolonged sweeping shots of Vietnam in Kubrick’s repertoire here. Only the same invasive camerawork for which he is now famous, camerawork that melds everything into a narrative, character or object alike.

Full Metal Jacket isn’t the best war film ever made – it’s arguably not even the best war film about Vietnam – but its introspective, close-up portrayal of war on the big screen marks a watershed moment in the genre. Kubrick’s film is remembered for screamed expletives and psychological abuse, but what perhaps should be remembered is the simple lives it explores in a war that was anything but. Joker’s sardonic bon mot, “I am in a world of shit. Yes. But I am alive. And I am not afraid,” is the takeaway from Kubrick’s tour of the seventeenth parallel. War is the story of individuals, not armies.

Published 5 May 2019

By David Hayles

Forty years after it left critics cold this majestic tragi-comedy stands as a testament to a true master of his craft.

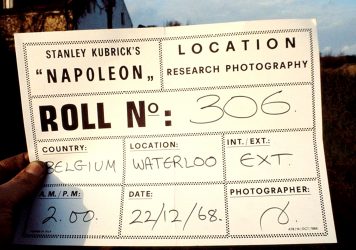

Scouting photos and script drafts shed new light on the greatest movie never made.

By Jeremy Carr

Released 60 years ago, the director’s masterfully coordinated World War One drama remains one of his finest achievements.