To think about sports and social justice is, above all, to think of Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the American sprinting duo who gave the Black Power salute on the podium at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City. Yet you may not be aware that at the same time women weren’t even allowed to compete in long distance running competitions, as detailed in a new documentary Free to Run. Amazingly, it wasn’t until 1984 that the women’s marathon was made an Olympic sport.

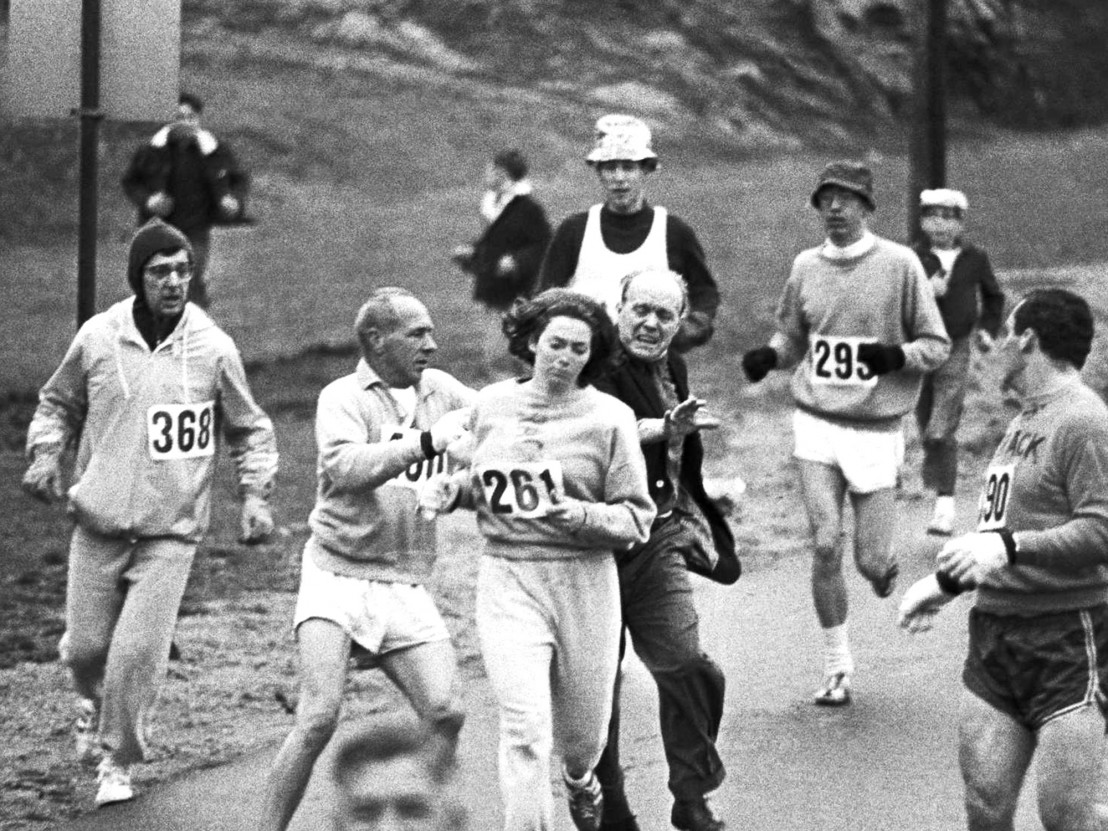

Directed by Pierre Morath, Free to Run charts the uphill struggle women runners channelling the spirit of Emily Pankhurst faced in winning the right to compete. At the Boston Marathon in 1967, jogging enthusiast Kathrine Switzer had attempted to run incognito by signing up as K Switzer, but halfway around the course an event organiser was snapped trying to drag her out of the race, teeth bared and arms outstretched.

The line from running associations and medical professionals at the time was that women couldn’t cope with running – they were supposedly carrying too much fat, were too emotional and there were even concerns, as one nurse explains with retrospective astonishment, that their uteruses might fall out in the process. Such were the lengths some went to to preserve the maleness of marathon running. Instead women were encouraged to pursue other, more graceful sports; gymnastics, say, or figure skating. In one interview Switzer expresses her bafflement at this idea because to her running had always seemed graceful enough.

As Free to Run shows, running is not only eye-catching but also a sport that involves a battle of the will. It makes sense, then, that films about running have tended to be about overcoming discrimination. In Chariots of Fire, perhaps the most famous film about running, hotshot sprinter Harold Abrahams is motivated by the suffocating antisemitism surrounding him, while in Michael Mann’s The Jericho Mile, Larry Murphy – who is serving a life sentence – is egged on to compete by the prison warden, who believes Murphy’s success will inspire other convicts to accomplish similar feats. In both films, running is seen as a way of shedding a badge of stigma: in the former, that of being Jewish in an antisemitic environment and in the latter, that of being a convict.

One of the reasons running works as a narrative device for these kinds of stories is that races usually take place in broad daylight so the athletes competing in them get seen and acknowledged by the rest of society. In Free to Run, not only were female competitors reversing the man as hunter-gatherer, woman as home-maker expectations of the time by competing in a physical event outside of the home, the fact that they were doing so in public meant they were helping to change public perception of what was ‘normal’ and socially acceptable.

You might think that a better way to show female empowerment in the movies would be driving. Still off-limits to women in Saudi Arabia, what better symbol could there be for being able to go where you please and escape domesticity? Thelma & Louise isn’t just the feminist film par excellence, it’s also a thrilling road trip. However, in the lore of Hollywood cinema at least, driving is more escapist than inspirational and films about it tend not to have messages about social change driving them.

In Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, Ryan Gosling’s Driver is a modern-day cowboy: cool, alone, and in control of his stead – he acts out of a sense of chivalrous instinct rather than any preexisting social ideals. That characters who drive are usually out for themselves rather than the common good makes sense, because while technically you’re out in public when you drive, to some extent you remain cut off from the world outside your car-shaped bubble.

While Thelma and Louise appears liberating, its message is actually a somewhat pessimistic one. From the outset Louise (Susan Sarandon) takes a fatalistic attitude about trying to change the misogynistic society they live in. “Who’s going to believe that? We just don’t live in that kind of world”, she says to Thelma (Geena Davis) after she is sexually assaulted outside a bar. It comes as no real surprise that after a cathartic sojourn through the country, when the authorities finally catch up to them they choose to drive off a cliff instead of fighting for their dignity and freedom through the courts.

Its explosive ending probably played a part in Thelma and Louise’s commercial and critical success back in 1992, but would a director include that scene if the film were remade today? You sense that in the age of the Bechdel test, when the demand for strong, powerful female characters is greater than ever, audiences might not be so willing to except such a fatalistic finale. Perhaps in an updated, more forward-thinking version of the movie, Thelma and Louise would be cast as long-distance runners instead.

Free to Run is released 16 September.

Published 14 Sep 2016

By Josh Hall

Twenty five years ago Ridley Scott’s road movie pointed the way for gender equality. So why has so little changed?

Is it possible for women to love movies which promote a regressive, misogynistic worldview?

The actor brought us to tears at her recent London Film Festival symposium.