In 1975, when Junya Sato’s The Bullet Train (Shinkansen daibakuha) was released, Japan’s Shinkansen, or ‘new main line’ – the world’s first high-speed train system – was only 11 years old, even if, in the decade since its opening in 1964, it had been extended across the country. These Bullet Trains were a symbol of Japan’s rapid progress – the barrelling momentum with which the nation was advancing, both technologically and economically.

Yet there were losers as well as winners in the post-war recovery. As Tetsuo Okita (Ken Takakura) sees his small business bankrupted by an increasingly centralised rail industry, leading to his financial ruin and divorce, he joins forces with downtrodden Hiroshi Oshiro (Akira Oda), who has recently been mistreated by another company after a workplace accident, and with one-time radical student revolutionary Masaru Koga (Kei Yamamoto), to execute the perfect crime, which will allow them to extort five million dollars and leave behind forever the country that they feel has already left them behind.

Having spent years building precision instruments for trains before his business failed, Okita has a characteristically meticulous plan for a bloodless revenge in which one of his own discontinued products will be key. For underneath the Special Express 109 traveling from Tokyo to Hakata, he has attached dynamite to his own tachometer, so that the train, with its 1500 passengers, is primed to explode if its speed drops beneath 80km per hour.

“He turned the train into a time bomb on wheels,” as the principled Kuramochi (Ken Utsui) puts it from the train company’s control room. Kuramochi is the moral centre of The Bullet Train, and about as close to a protagonist as we get in a film that divides its attention between a large ensemble of characters.

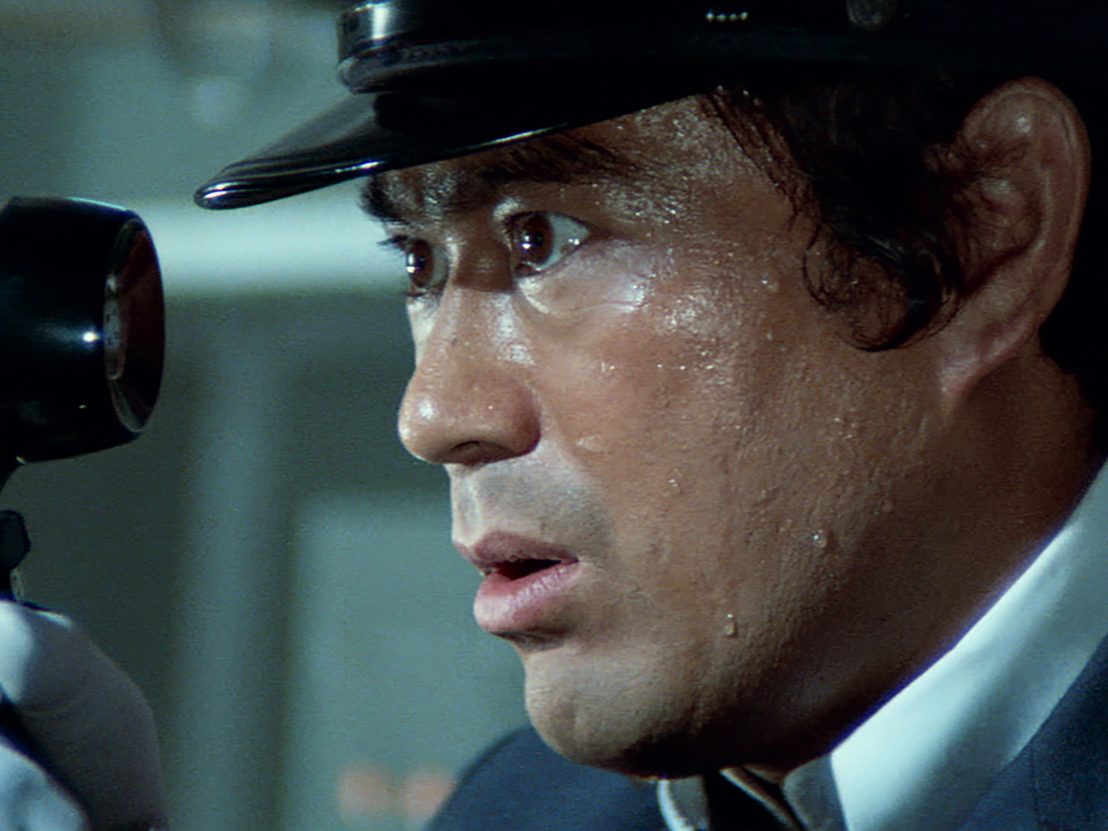

On board the train there is the stressed, sweaty driver Aoki (Shin’ichi ‘Sonny’ Chiba, cast very much against action-hero type) and his put-upon conductor Kikuchi (Raita Ryu), various panicking, mutinying passengers including a rock band and the film crew documenting them, the heavily pregnant Kazuko Hirao (Miyako Tasaka) and, under police escort, the convict Shinji Fujio (Eiji Go) who by chance is rather familiar with the bombing gang.

Meanwhile on the ground is a large team of train company officials, network operators and police, all racing to locate both the bomb and the bombers while keeping the train in motion and the passengers alive. And then there are the criminals themselves, drawn with some sympathy even if, for all the precision of their planning, they prove to be losers no less now than they were in all their previous endeavours.

In The Bullet Train, the police are extremely efficient at tracking the perpetrators down via some highly tenuous clues, even if coincidences work as much against them as in their favour. In one sequence, for example, a university judo team happens to be in the right place at the right time to help stop one of the bombers, while in another, a random fire that breaks out at a cafe prevents the police getting their hands on crucial instructions left for them by Okita (“What? It’s unbelievable!” comments the ever exasperated Aoki, his disbelief mirroring the audience’s at this improbable happenstance).

Here things go wrong as much as they go right, as plans constantly have to be revised, moves improvised and risks taken, adding to tensions that are already high-speed to the point of exploding. There is a lot going on, all at once, and Sato, co-writing with Ryunosuke Ono, deftly keeps the different narratives running along their parallel tracks.

It is easy to see the influence of The Bullet Train on Jan de Bont’s Speed (1994), with its similar premise of a bomb that will explode when the vehicle on which it has been placed travels beneath 50 miles (80 km) per hour, even if Speed’s writer Graham Yost has insisted that he was in fact inspired by Andre Konchalovsky’s Runaway Train (1985) instead – itself based on a Japanese screenplay from the 1960s by Akira Kurosawa.

Yet several of the essential ingredients which this big-budget Toei production has, Speed decidedly lacks: an earnestness that precludes comedy or romance, a moral messiness that refuses to paint things in black and white, and a principal antagonist who, for all his flaws, is no cartoon villain. No surprise then that Sato’s film also appears to have had an influence on Michael Mann’s noirish action thriller Heat, especially in its climactic sequence on an airport’s tarmac.

“How I miss the old steam locomotive days,” complains Aiko at one point, in nostalgic resistance to the onrush of the new. “You’re not on the old locomotive,” replies Kuramochi over the radio. “It’s a bullet train. This is a real test of the new control system.” Viewed today, The Bullet Train may seem dated by Okita’s extensive use of now outmoded pay phones to contact the authorities – but the high-speed trains which were at the forefront of Japan’s modernisation in the 1960s and 1970s still seem cutting-edge today, especially by the standards of the United Kingdom’s rail services. Once the train has been safely brought to a halt after an ordeal lasting many hours, the network boss tells its extremely stressed driver: “We can restart the train in 30 mins. Take a nap until then.” Evidently there can be little stopping progress.

The Bullet Train is released on Blu-ray by Eureka!, 24th April, 2023

Published 24 Apr 2023

By Anton Bitel

Shinichi Fukazawa’s Super-8 gem Bloody Muscle Body Builder in Hell is a throwback to ’80s horror.

By Anton Bitel

Destruction Babies is raucous rebel filmmaking at its brutal best.

The ’90s straight-to-video boom reinvigorated the industry and made stars of directors like Takashi Miike.