In her 1984 review of Stop Making Sense, Pauline Kael describes David Byrne as having “a withdrawn, disembodied sci-fi quality, and though there’s something unknowable and almost autistic about him, he makes autism fun.” While perhaps coming off as insensitive now, this sentiment regarding Byrne’s strangeness was widely shared by both his bandmates and critics alike since Talking Heads’ inception. Byrne’s struggle with social conventions and interactions has been a near-impossible topic to avoid when examining the otherworldly genius of the group and their outsider appeal. Forty years have now passed, and not only has A24 restored and re-released Stop Making Sense to commemorate the concert film’s anniversary, but the man behind the big suit now proudly identifies as autistic. Reexamining the film with Byrne’s neurodivergence in mind, the film dubbed “the greatest concert movie of all time” concurrently becomes one of the greatest autistic narratives ever put to film.

As Byrne first walks out onto the Pantages Theatre stage, acoustic guitar and boombox in hand, two narratives simultaneously introduce themselves through the structure of the concert itself. The history of the band’s formation and the construction of their sound is visually illustrated through each member appearing on stage one after the other, starting with Byrne alone and playing Talking Heads’ first single “Psycho Killer”, culminating with the entire band and guest performers assembled to play their next major hit “Burning Down The House”. In a Q&A for the film back in 2014 however, Byrne argues that there is another more “psychological narrative” at play – a sentiment he has since repeated on Talking Heads’ current press run. In this narrative, the film starts off with an anxious man alone in the world, who, through the help of his band members surrounding and playing alongside him, lets go and is liberated, finding joy in connection through music. “It’s a whole catharsis thing,” Byrne concludes.

Byrne’s difficulties adhering to “normal” social behaviour colors much of Talking Heads’ lyricism, and is thematically employed in Stop Making Sense to fit this psychological narrative. The film is bookended with two songs evoking intense anxiety, beginning with “Psycho Killer” including stressful lyrics such as “I’m tense and nervous and I can’t relax” and “Don’t touch me I’m a real live wire”, and ending with Byrne yelping “Lost my shape trying to act casual / Can’t stop, I might end up in a hospital” in the film’s final number “Crosseyed and Painless.” Both songs come from the perspective of a man in crisis, but while the first may conjure up images in the listener’s mind of a knife-wielding Norman Bates, both can also be interpreted as an overwhelmed autistic man struggling to fit into “normal” allistic society, teetering on the verge of a meltdown.

Contrary to the film’s title, it is clear that Byrne is desperately trying to make sense of both his feelings and the world around him, though he is beginning to realize that none of it makes sense. The incessant questions shouted in “Once In A Lifetime” like “How do I work this?” and “My God, what have I done?” as Byrne hits himself on the head and convulses exemplify this, struggling to wrap his head around and conform to the social norms laid out in the song. Visually this struggle is conveyed in performances such as “Making Flippy Floppy”, wherein the seemingly random words projected behind the band members such as “VIDEOGAME, SANDWICH, DIAMONDS” and “STAR WARS, FACELIFT, PIG” leave us as an audience mystified for their meaning despite understanding each concept individually, much like how Byrne feels while navigating a confusing neurotypical world.

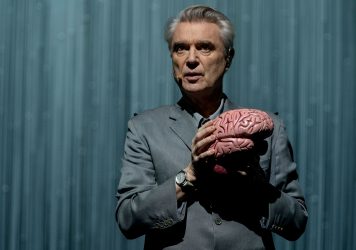

Costuming is another way that otherness is metaphorically represented in the film. Most obviously, in a sea of homogenized grey outfits worn by everyone on stage (ignoring drummer Chris Frantz’s blue polo annoyingly breaking continuity), Byrne sticks out like a sore thumb as he jitters and shakes in his iconic big grey suit. But even before this, when Byrne is in his regular clean-cut grey formal wear, he, unlike the protagonist of “Life During Wartime”, is unable to blend in with the crowd. Through Byrne’s costume metamorphosis, we witness the powerful journey of a man unmasking.

Masking, the suppression of neurodivergent traits and the adoption of neurotypical behaviour in order to blend in with an allistic society is a stressful and exhausting endeavour that David Byrne seems all too familiar with. He struggles to maintain this facade of normalcy throughout the show thanks to both his lyrics and his uncontrollable repetitive movements and noises giving him away, at times reminiscent of autistic stimming (Think how much sounds and phrases are repeated in Talking Heads’ oeuvre, most famously lines like “Same as it ever was”).

As the show progresses and Byrne begins to let loose, he unmasks himself in front of both his band and his audience, revealing his larger-than-life persona as he emerges from the shadows after Tom Tom Club’s interlude, taking up space as his fully unique and silly self. Wonderfully, Byrne has kept up with this motif of displaying difference proudly while reuniting with his former band members during A24’s current Stop Making Sense press run and live Q&As, with Byrne standing out in blue and white suits while the former Heads don all-black.

Since his early art school days of playing under the name “The Artistics” (nicknamed “The Autistics” around campus) to his present-day legacy status as an influential new wave pioneer, David Byrne has been unable to escape one question from onlookers his whole career: How can someone so shy and introverted go on a stage and do what he does? In retrospect, Byrne knows the answer, explaining in his 2012 book ‘How Music Works’ that performing his art was “a means of entry into conversation”, a way to reach out to others and build community when regular face-to-face conversation was uncomfortable for him.

Revisiting Stop Making Sense forty years later, it feels as though many of the choices Byrne conceived for the stage (along with Demme’s directorial choices) work to challenge stereotypes regarding neurodivergence while also joyously celebrating difference. Here autistic people are “strange but not a stranger”, represented as being more than capable of expressing love and connecting with others, just doing so in their own unique ways, like singing a love song to a lamp, for instance. The title, Stop Making Sense, is David Byrne’s plea to you as a viewer to not make yourself palatable to the social norms of allistic society, and to instead choose happiness by unmasking and freeing yourself. As Byrne sweetly stated to a fan asking about his autistic identity, “We all don’t have to be the same.”

Published 29 Sep 2023

Spike Lee’s filmed version of David Byrne’s celebrated concert shows a pop master at the peak of his powers.

By Thomas Hobbs

The composer reflects on how David Byrne’s endearingly weird soundtrack inspired her to become a musician.

By Callie Petch

Adam Smith creates a disorientating, immersive experience through innovative camera work and editing in The Chemical Brothers: Don't Think.