Following the announcement that über-method man Daniel Day-Lewis is hanging up his acting spurs – his last film will be Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread – thoughts inevitably turn to which roles this celebrated screen actor will be most remembered for. You could make the case for his Oscar-winning turn as disabled artist Christy Brown in My Left Foot, or as ego-the-size-of-Texas oilman Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood.

Then there’s his turn as Czech doctor Tomas in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, which prompted Pauline Kael’s memorable description of Day-Lewis in the New Yorker as a “muscular toothpick”. Personally, I will always love his all-action portrayal of frontiersman Hawkeye in Michael Mann’s The Last of The Mohicans.

The film opens on three Mohawk tribesmen charging through the forests of mid-18th century New York State. The man leading the way stands out not just for his speed but also his ethnicity – he’s unmistakably a white man in Native American dress. This is Hawkeye, adopted son of Mohawk leader Chingachgook. Everything about him reveals a man at one with his environment: his grace, his drive, his single-minded intent. An off-camera war between the British and the French for control of the American colonies is raging, but Hawkeye and his companions’ focus is unwavering.

Life and death are being decided elsewhere, but this is no different. The Mohicans are hunting elk and their livelihood is at stake. Naturally, it’s our hero Hawkeye’s job to make the kill. And with at least a minute to reload a flintlock rifle, it really is a one-shot kind of deal. The camerawork by Dante Spinotti (who also worked with Mann on Heat and The Insider) is stunning, and captures the moment of aiming-to-shoot in three different frame sizes: first a long shot taking in the whole of Day-Lewis’ physicality as Hawkeye raises his enormous rifle with calculated precision; then closer on him from the waist up; then tighter still, just his face and the gun. Rack focus to the muzzle as it fires. And in the moment of death, as the animal drops to the ground, the music cuts out.

It’s no accident that Day-Lewis looks so at home with a weapon in the wilderness. We’ve all heard the stories of his commitment to preparing for roles. With The Last of the Mohicans, this involved learning to survive in a forest: trapping and skinning animals, making fires, firing guns on the run. On a Blu-ray extra Day-Lewis explains, “There’s no wasted experience if in the discovery of it, you’re becoming at ease with it.” It’s not simply about learning to load and fire a gun in the wilderness, it has to be convincing, it has to look like he’s done it a thousand times before. When Hawkeye shoots that elk, we feel the character’s experience and expertise. He’s done this before, and he’ll do it again.

Such dedication to immersing himself in each role invariably leads to great performances, but there is a downside to this approach: what to do when filming is over. Day-Lewis has spoken of this comedown period as one of “bereavement”, a situation in which “no part of you wishes to leave that character behind.” This helps to explain the frequently lengthy breaks between projects and his current wish to call it a day. Of course, it’s not the first time he has appeared to walk away from acting.

Day-Lewis famously took ‘semi-retirement’ in the late ’90s, at one point training as a cobbler in Florence. Was he secretly prepping for a role? Apparently, he just really likes shoes. Day-Lewis returned to acting for Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, but there’s something fascinating, almost romantic, about an actor willing learn new skills, a new craft, for their own sake rather than for a specific part.

The word now is that Day-Lewis plans to throw himself into dressmaking, having fallen in love with fashion design while researching Phantom Thread. But, as with shoemaking, one can’t help but wonder if this will prove to be just a lengthy hiatus. This is a man who loves to learn new things, often becoming new people in the process. Ultimately, an actor always needs an audience.

Published 15 Jul 2017

By Colin Biggs

Released 10 years ago, Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2007 masterpiece contains an anti-capitalist message that rings especially true today.

By Taylor Burns

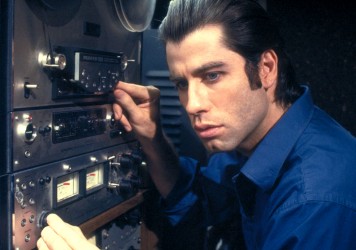

Brian De Palma’s taut Watergate-era thriller highlights the difference between what a country believes itself to be, and what it actually is.

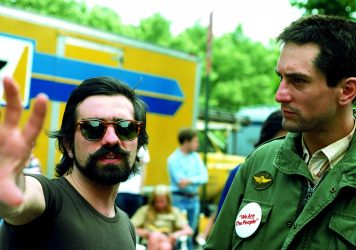

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.