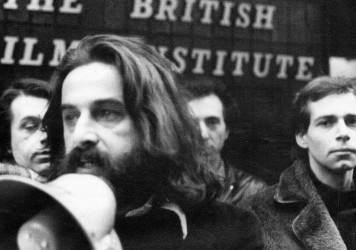

Twenty five years ago, on Saturday 19 February, 1994, the British artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman died from an AIDS-related illness.

A true pioneer of British independent cinema, he left behind a remarkable body of work, ranging across long-form features, Super-8 shorts and music videos shot for the likes of the Smiths, the Pet Shop Boys and Marianne Faithful.

Though his career was cut short, Jarman undoubtedly left his mark. His first feature, Sebastiane, caused outrage upon release in 1976 for its all-Latin script and explicitly gay characters. That was followed two years later by Jubilee, in which Queen Elizabeth I gets taken on a time-travelling journey to the violent, chaotic punk era.

The best actors of Jarman’s generation chose to work with him. He directed Sir Laurence Olivier’s last film, worked with Judi Dench, Robbie Coltrane, Sean Bean and formed a fruitful collaboration with a young Tilda Swinton.

Jarman also left an important social and political legacy, being one of the first public figures to discuss his HIV diagnosis openly. He was an activist for a range of LGBT issues, notably his vocal opposition to ‘Section 28’, an amendment that made the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ illegal for local authorities and is now widely seen as an example of state-supported homophobia.

These two legacies, artistic and social, meet in his final film, Blue. It consists of a static blue image, in a shade of artist Yves Klein’s ‘International Klein Blue’. Accompanying this unmodified colour is a soundtrack comprising music and narration from Jarman, Swinton, Nigel Terry and John Quentin. The narration mixes recollection, poetry and anecdotes from Jarman’s hospital diaries, at a time when he was temporarily blind due to an AIDS-related infection in his retina that left him able to see only in blue.

Like many other Jarman works, the way Blue was screened made it revolutionary. It wasn’t displayed as an avant-garde piece in an art gallery, but broadcast to the nation on Channel 4 and BBC Radio 3. A 70-minute film about HIV without a moving image was about as radical as it got in 1993.

“In the pandemonium of image, I present you with the universal blue. Blue, an open door to soul, an infinite possibility becoming tangible,” reads a narrator.

Jarman’s film pushed the boundaries of popular cinema, just as Yves Klein and others had re-defined what art could be earlier in the 20th century. It offers infinite possibilities for us to imagine what we hear in our own way. Unlike radio, there is something to look at – a point of focus – but no new image to distract or guide the mind. Each viewer necessarily has a unique experience.

For Jarman, the film was a chance to talk openly about HIV, which at that time was a political act in and of itself. “I wanted to convey some of what I’d seen, and the disaster which I’d been living through for the past few years,” he said to the BBC before a screening in Edinburgh.

As society continues to grapple with how it remembers, or fails to remember, those it lost to HIV/AIDS, the imagery has lost none of its power:

“David ran home panicked on the train from Waterloo, brought back exhausted and unconscious to die that night. Terry mumbled incoherently into his incontinent tears. Others faded like flours cut by the scythe of the blue-bearded reaper.

“Parched as the waters of life receded, Howard turned slowly to stone. Petrified day by day, his mind imprisoned in a concrete fortress until all we could hear were his groans on the telephone, circling the globe.”

Although intrinsically linked to Jarman through the narration being taken from his hospital diaries, the film is also impersonal, poetic and evades simple categorisation or explanation. It draws on all kinds of influence, from the Odyssey to Christian poetry, and weaves an experience rather than a story.

The film ends with the lapping of the sea and the chiming of a bell: “No-one will remember our work. Our life will pass like the traces of a cloud, it will be scattered like mist that is chased by the rays of the sun. For our time is the passing of a shadow. Our lives will run like sparks through the stubble. I place a delphinium, blue, upon your grave.”

I hope not. In the spirit of Jarman, rejecting rigid ideas of plot and form, perhaps the opening lines are a good place to end: “Love is life and love lasts forever. My heart’s memory turns to you, David, Howard, Graham, Terry, Paul…”

Published 16 Feb 2019

Read an exclusive extract of a long-lost conversation between these innovative French filmmakers.

By Sam Thompson

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.

Shelagh Delaney’s voice stood out from the angry young men who dominated British cinema in the mid 20th century.