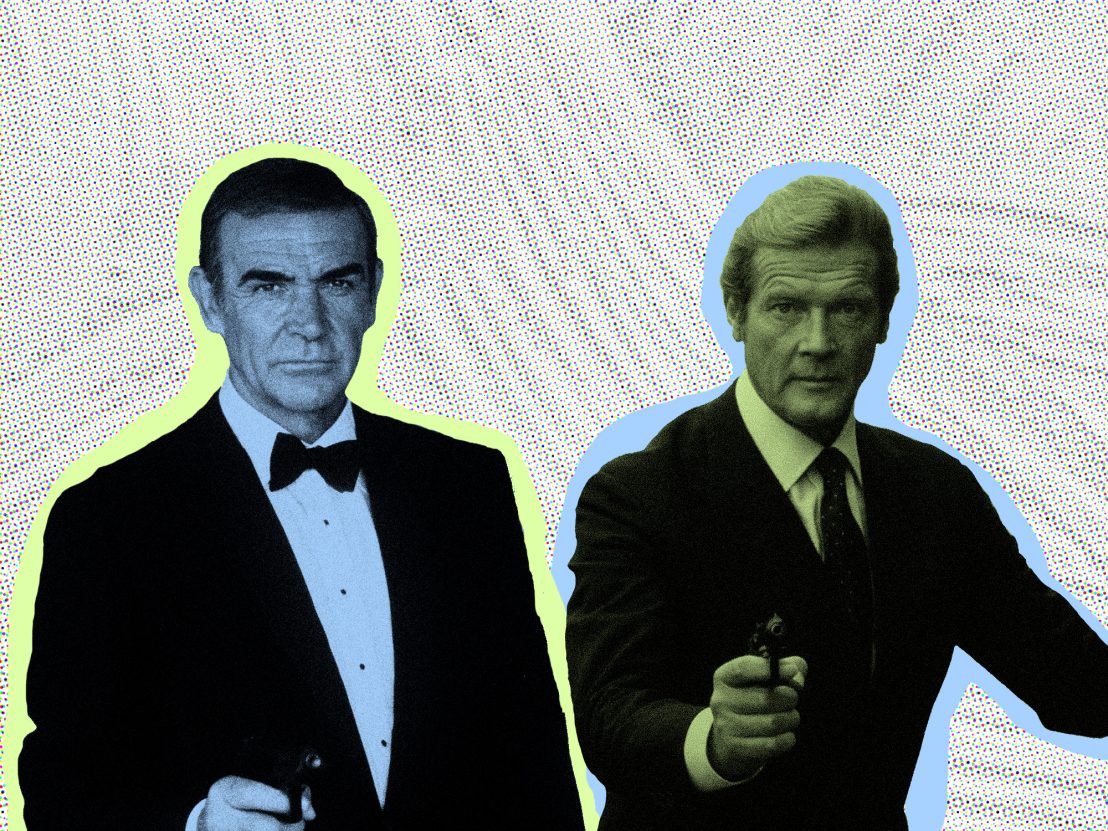

James Bond has fought megalomaniacs across the world, but rarely has he battled his most dangerous enemy – himself. Forty years ago, the thirteenth Bond adventure (and sixth starring Roger Moore), Octopussy, faced competition from a rival 007 picture: the “unofficial” Never Say Never Again. A remake of 1965’s Thunderball, this pretender to the Bond throne had an ace up its sleeve – a surprise comeback from Sean Connery, in his first appearance as Bond since quitting the series in 1971. But how could this happen?

The brainchild of executive producer Kevin McClory, Never Say Never Again had its origins in the early 1960s – before producers Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman formed Eon Productions and kickstarted the Bond movie franchise as we know it today. The complex and lengthy legal entanglement which surrounded McClory’s rival project is explored in Robert Sellers’ excellent book, The Battle for Bond. As the author summarises, it was “40 years of lawsuits, court cases, injunctions, betrayals, deaths and broken lives.”

“McClory had the legal right to make an ‘unofficial’ Bond film because prior to the Broccoli/Saltzman series, the Irish filmmaker worked with Ian Fleming on a proposed Bond picture, to be called Thunderball,” Sellers tells LWLies. “When that project failed, Fleming used the discarded screenplay as the basis of his next Bond novel, but without the permission of McClory, who had worked on the story and contributed substantial plot ideas. The Irishman sued and won a plagiarism case against the author that resulted in a suitcase full of money and the film rights to Thunderball. This is the reason why 1965’s Thunderball is co-produced by McClory, and why he was able to remake the Thunderball story.”

McClory handed the reins of his nascent Bond picture to producer Jack Schwartzman and director Irvin Kershner, but the film’s “unofficial” status left them in legal limbo. “We had a great deal of problems getting a script,” reflected Kershner, as reported in Sellers’ book. “To make a film we would have to take freedoms, and every time we tried to take freedoms Eon and United Artists would somehow get wind of it and start to sue us that we weren’t using the book. We were kind of trapped in the middle, and there was no easy way out.”

Never Say Never Again had access to many of the key ingredients to the Bond formula – his allies M, Q, Moneypenny, and Felix Leiter are all present, as is the requisite globetrotting, violence and sex – but Kershner was denied some of the most identifiable tropes. The opening gunbarrel sequence and Monty Norman’s theme music, for example, are property of Eon. But the problems with Never Say Never Again go well beyond a few missing motifs; it’s a tasteless and achingly dull film which lacks the polish or spectacle expected of the Bond brand.

These failings are thrown into sharp relief when compared with the “official” Octopussy, possibly one of Roger Moore’s less celebrated Bond efforts, but nevertheless a fine entry in the series. Filmed in striking locations from Udaipur, India, to Checkpoint Charlie in West Berlin, it’s a fun Cold War thriller with a surprisingly down-to-earth plot, dealing in topically Thatcherite concerns of European security and nuclear disarmament. Moore, now a decade into his tenure as Bond, is completely at ease in his familiar dinner jacket, while French actor Louis Jourdan plays the villain Kamal Khan with sinister sophistication.

John Glen’s unshowy direction continues the larger-than-life spirit of Moore’s Bond while avoiding a descent into self-parody. A standout sequence features 007, disguised as a circus clown, defusing a nuclear bomb on an American air force base – it sounds laughable, but the sincerity of Moore’s performance sells the moment. Meanwhile, the stunt work is uniformly stupefying – a climactic bout of airborne fisticuffs atop a twin-engine plane is as impressive as anything Tom Cruise could conjure. The sense of grandeur is bolstered by John Barry’s stirring score and Peter Lamont’s opulent production design, to which the nondescript locations of Never Say Never Again have no response.

“Octopussy showcases original, ground-breaking action in air and on land, with stuntmen standing in for the 55-year-old Roger Moore, while doubling down on Eon tropes, particularly Monty Norman’s James Bond theme,” Ajay Chowdhury, co-author of Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films, tells LWLies. “Never Say Never Again showcases its most expensive special effect; the returning Sean Connery, who is kept front and centre.”

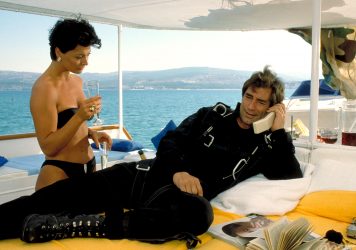

Other than Connery’s typically electric screen presence, however, Never Say Never Again is a curiously anaemic film. Kershner’s direction is languid, while the script is muddled and betrays a poor understanding of Bond and his appeal. Connery’s ageing 007 is less of a problematic womaniser and more of an outwardly creeping letch, at one point disguising himself as a masseuse in order to grope Kim Basinger.

Efforts to capture the eighties zeitgeist also do the film no favours, from the warbling synths of Lani Hall’s title song to a frankly baffling scene in which the villain, Maximilian Largo, challenges Bond to a duel over an arcade game. Compare this tedious confrontation with the corresponding episode in Octopussy, in which Bond outwits Kamal Khan in a game of backgammon – it’s drenched in the heady blend of elegance and danger for which the Bond films are celebrated.

“Never Say Never Again proved it was never Connery or any lead actor as Bond who created that movie magic,” Mark O’Connell, author of Catching Bullets: Memoirs of a Bond Fan, tells LWLies. “Octopussy has a sense of original craft, fantasy, style, scope, presentation and swagger about it. Never Say Never Again always feels like a curious TV movie – re-dressing existing locations rather than building its own, swapping Europe’s finest movie tailoring for Bond in a pair of ill-fitting dungarees and commissioning a score that sounds like a jazzercise session rather than the lush strings and brass of John Barry. It does, however, have its plus points – Barbara Carrera’s delicious vixen Fatima Blush, Klaus Maria Brandauer’s brilliantly bland villain Largo and, yes, the return of Connery.

“Yet, Never Say Never Again rarely feels the sum of its parts. Shot by the cinematographer of Raiders of the Lost Ark, costumed by the man who dressed Blade Runner and directed by the guy that helmed The Empire Strikes Back, it lacks the collective sheen of those talents.” In the end, the better film won, with Octopussy taking $182 million at the global box office against Never Say Never Again’s (still impressive) $159 million.

It would take more than a freshly bewigged Connery to overcome the well-honed professionalism which has always raised Eon’s Bond series above its competitors and imitators. But the real winner of the confrontation was the showbiz press, who revelled in this battle of the Bonds. “Connery and Moore were good friends. The 1983 ‘rivalry’ was nothing more than a great, obvious piece of PR – with Never Say Never Again arguably riding the coattails of Moore’s momentum as Bond,” says O’Connell.

Beyond its qualities as a film, there’s a cynicism to Never Say Never Again which leaves a bitter taste. It stands on the shoulders of a giant, relying on brand recognition in order to profit from an icon which others had spent decades building. It predicts the recent trend for reboots, sequels and “cinematic universes”. Looking at the latest cycle of “live action” Disney remakes, for example, from Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella to Rob Marshall’s upcoming Little Mermaid, it’s difficult to see much creative impetus beyond the desire to make a quick buck from existing intellectual property.

When Kevin McClory died in 2006, his Bond rights were swiftly secured by Eon, bringing the messy saga to a conclusion. But 40 years on from the battle of the Bonds, competing franchise films may yet become a familiar sight in Hollywood, as more literary characters go into the public domain. The recent Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey is a vivid demonstration of what’s possible when classic movie studio properties fall out of copyright, with Bond himself currently scheduled to go public in 2035. It seems there are plenty of lawsuits, betrayals and broken lives still to come.

Published 26 Apr 2023

From Dr No to Skyfall, Bekzhan Sarsenbay explores the trends and motifs of a movie institution.

By Mark Allison

With a new 007 and more progressive sexual politics, this film brought the series up to speed with the modern world.

By Mark Allison

In The Living Daylights and Licence to Kill, Dalton created the template for Daniel Craig’s hard-edged 21st century Bond.