“Anything can happen, in any kind of scenario, on any given day. No one is spared, everyone is susceptible.” In describing what attracted him to Brad Pitt’s new film, World War Z, a global action drama in which UN investigator Gerry Lane (Pitt) leads a desperate attempt to stop humanity coming to an un-dead end, director Marc Forster is clear that the universality of the threat was key. “I wanted to create a movie that feels real, so audiences feel like this could happen, this minute, to any one of us,” he says.

With Pitt as an everyman hero – “Gerry can’t fly, he can’t beat up bad guys… he has no super-powers. He’s a dad, with a burning need to keep his family safe,” the actor says – and the entire planet affected, World War Z is a fantastic but credible depiction of disaster.

But although its verisimilitude might be unusual, conceptually World War Z is merely the latest in a long line of worldwide catastrophe movies. And while subjecting the human race to great peril might be entertaining, each film also says something about the primary concern of its day, whether that be nuclear or germ warfare, scientific experimentation, overpopulation or rampant capitalism.

The principal has literary origins. Secular writers have set out apocalyptic visions of plague since at least the eighteenth century, and in later years found inspiration in profound technological or societal shifts. Rapid and dramatic advances in science saw Victorian fantasies of mad inventors holding the world to ransom, seized upon by cinema’s pioneers. The First World War made real the mass slaughter possible with such weapons, and the overwhelming impact of World War 2 and its atomic dawn was an obvious starting point for the post-war generation.

As man stepped tentatively beyond the earth and into space alien invasion actually seemed possible, although from the viewpoint of the United States this was clearly tinged with displacement anxiety – less green men from Mars than Reds under the bed. An unearthly foe of a different kind was the astronomical body on a crash course for our small blue globe.

The range of films reflecting this unease is therefore vast, from the Cold War paranoia of Them! and The Day The Earth Stood Still through the dystopian classics of the 1960s and ’70s such as Soylent Green, Logan’s Run and Rollerball (as well as little-seen gems like The Ultimate Warrior or Saul Bass’ Phase IV) to Children of Men, The Road and The Book 0f Eli today. Evolution, though at first a sign of enlightened understanding, drove the primal scream that was Planet of the Apes, while The Andromeda Strain conflated space exploration, nuclear annihilation and biohazard research. Those worrying lumps of rock hurtling through space saw a response in Meteor, Armageddon and Deep Impact.

The film adaptation of Max Brooks’s 2006 novel ‘World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War’, then, allows any number of interpretations. Pitt – who is also co-producer – sees a parallel in recent health scares, with the zombie contagion “spreading much like we’ve witnessed viruses such as SARS travel. What happens when this jumps the fire break…what happens when everything we concern our days with is rendered useless?” Fellow producer Dede Gardner views the story as a metaphor for disengagement: “People are tied to their screens and their monitors and their headphones – in the most basic sense, they do walk around like zombies by not interacting with other human beings.”

Underlying theme aside, the principal challenge common to many of these productions is the realisation of destruction and desolation on a vast scale. Capturing abandoned cities and derelict buildings on screen once meant a few snatched minutes of location filming in the early hours before retiring to the backlot, but the digital revolution has brought lighter cameras and computer-generated imagery, yielding far more convincing vistas.

Resolving that “Audiences are smart, they know what different cities around the world look like”, Gardner accordingly steered filming around the world, although work in the scripted locations was supplemented by footage shot in other, more accessible, cities carefully chosen to match. Thus Glasgow stood in for Philadelphia, with a fortnight’s shooting in George Square, whilst Malta played Jerusalem. The Royal Navy lent the production a serving vessel, RFA Argus, to represent the fictional American helicopter carrier USS Madison.

Designing the movement of the infected victims, the team borrowed from the natural world to create zombies that Gardner says are “stagnant, slow and wandering” when dormant, but when aroused to feed become what movement specialist Ryen Perkins-Gangnes describes as “rapacious and relentless”. Many of the crew had experience filming simulated combat, bringing additional realism.

However it is made and whatever it might reveal of the present, World War Z joins a series of films that provide an alternate commentary on our times. Each of them is in the end about the same thing: fear. Fear of the different, fear of the other, fear of what’s outside and what’s inside. Fear, ultimately, of ourselves.

Chris Rogers writes on architecture and visual culture at chrismrogers.net

Published 5 Jun 2013

How come there are no people in the world of this new James Bond movie?

The third instalment in the rebooted comic book franchise is a colossal failure on every conceivable level.

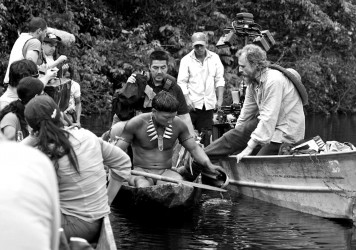

Embrace of the Serpent director Ciro Guerra on the logistical and spiritual challenge of shooting in a rainforest.