As he’s being dragged through the halls of a police station, the young man at the centre of François Ozon’s Summer of 85 issues a warning right at the outset: “If death doesn’t interest you, if you don’t want to hear about a corpse I knew when it was alive, if you don’t want to know what happened to him and me, and how he became a corpse, you’d better stop right here. This is no story for you.”

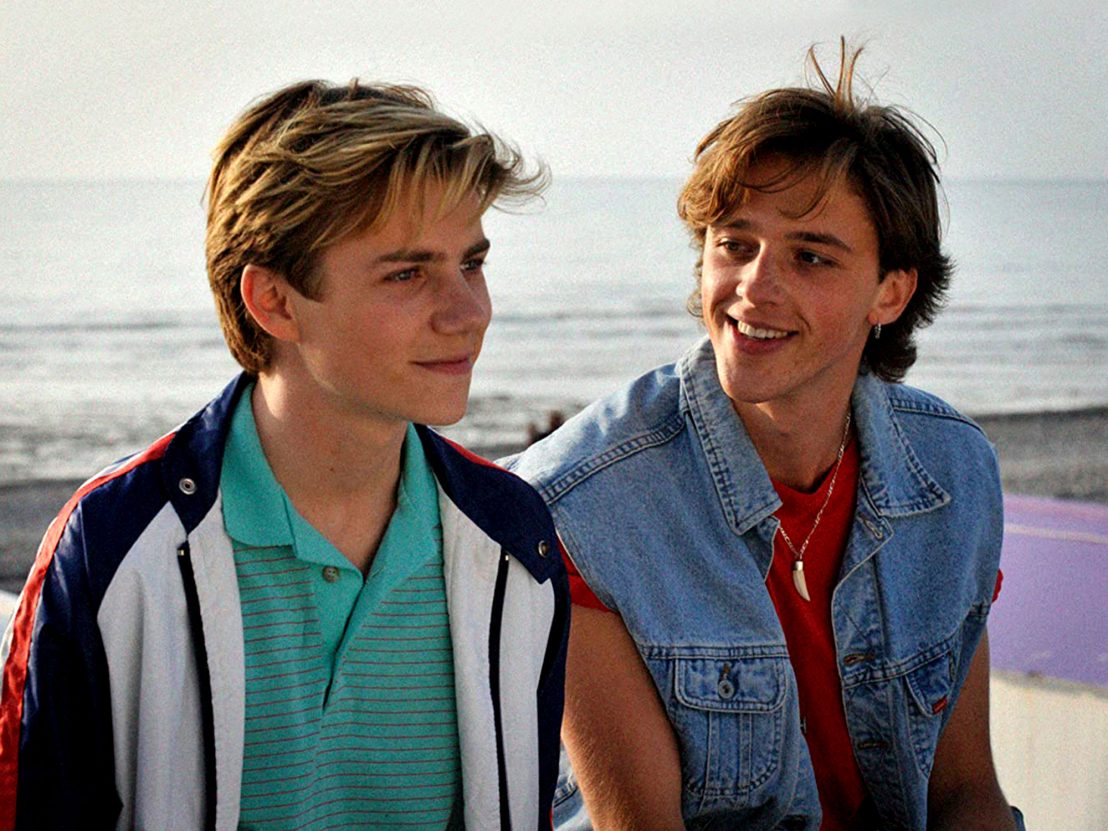

There’s a jolting sensation to being told not to watch a queer film from the get-go, especially one marketed with two boys, seemingly in love, holding each other as they ride a motorcycle off into the sunset. But as soon as Alex (Félix Lefebvre) finishes his statement, Ozon launches us into a more optimistic portrait of the 1980s, playing The Cure’s ‘In Between Days’ over a sunny coastal town.

As with so much of Ozon’s filmography, Summer of 85 is designed to pull the viewer back and forth between vastly different tonal experiences without ever feeling like they’re disconnected from one another. This is, after all, the director who delivered a Bergman-esque drama with Under the Sand, pivoted to a camp musical murder mystery with 8 Women, and then segued into creating a subtle erotic thriller with Swimming Pool back to back.

Adapted from Aidan Chambers’ ‘Dance on My Grave’ – one of the first YA novels to depict homosexuality without judgment – Ozon’s film navigates two stories at once: that of first love and that of first loss. There is mystery to the way the film and novel frame the story with its protagonist reflecting on his past relationship and all its volatility while simultaneously showing us how the romance blossomed in the first place.

Upon finding himself rescued after capsizing, Alexis (Félix Lefebvre) falls head over heels for his saviour David Gorman (Benjamin Voisin), a young man who’s as charming as he is dangerous. The magnetism between them (both the actors and characters) is undeniable, resulting in them doing everything one might expect them to do together, from hitting the amusement park to working at the same store (that David’s offbeat mother runs after his father’s death), if only to be together for yet another moment.

We see Alexis experience these things with hindsight, embroiled in a police investigation involving a dead body, heavily implied to be David’s. He processes this with help from his literature professor (Melvil Poupaud), who encourages him to write his story (casually reinforcing the joke among queer people that their best friend in high school is their literature professor). But the film’s Patricia Highsmith-esque proximity to crime is something more of a red herring, as Summer of 85 is rather lovingly preoccupied with the highs and lows of an unconventional, or queer, relationship.

“When you’re queer, every relationship comes with extra baggage, but the first one has a certain weight; an uncertainty to every action.”

This is something Ozon has played with in the past through various lenses: writer and subject in Swimming Pool; reader and writer in In the House; therapist and patient in Double Lover; captor and victim in Criminal Lovers; the list goes on. But despite the relationship between Alexis and David coming across as more traditional than those, presenting the beats of summer love with real tenderness, the film outright rejects the more melodramatic beats of many a contemporary gay romance.

Ozon’s fixation on the way relationships transform us is as evident here as elsewhere. The last decade in particular has found him fascinated with death’s impact on them, each film its own unique dive into it. The New Girlfriend explores gender identity through this lens, with one’s death being the catalyst for another’s transformation, while Frantz allows its protagonists to find fulfilment beyond the baggage of memory while also acknowledging that not everyone has a chance to truly move on.

When you’re queer, every relationship comes with extra baggage, but the first one has a certain weight; an uncertainty to every action. You’re always cautious of what the expectations of those around you might be, of the implication that you’re doing something abnormal in the eyes of society. Alexis’ parents talk around his uncle, seemingly shunned by the family for his queerness, while David’s mother pivots from doting to monstrous when she discovers the romance between the boys is what led to her son being taken from her.

The film always juxtaposes these highs and lows: holding hands on an amusement park ride is followed by a fight and accusation of faggotry and a passionate dance together in a club is mirrored by feverish movements to the same song on someone’s grave. Its most absurd moment takes a scoff at the idea of wearing a dress while on an upbeat date (with the outfit in question being a direct reference to his 1996 short film A Summer Dress) and turns it into an extended sequence in which Alexis must dress in drag and pass as a woman to merely see his lover one last time.

These are young men who are expected to follow in the footsteps of their working class fathers, living out the existence predetermined for them by society and their families. But Chambers’ novel and Ozon’s film are well aware that to be queer is to escape these pre-drawn maps, and though the lives of queer lovers are often coated in tragedy, ending with tears in front of a fireplace, Summer of 85 offers true hope beyond loss.

Summer of 85 is released 23 October via Curzon. Read the LWLies Recommends review.

Published 21 Oct 2020

Fans of André Aciman’s 2007 novel reflect on what makes it so special.

By Elena Lazic

François Ozon turns back the clock for a sun-kissed gay love story that’s shot through with tragedy.

Levan Akin’s And Then We Danced has put LGBT+ rights centre-stage in the conservative, Orthodox country.