The first time I read ‘Call Me by Your Name’ I stayed up until 4am to finish it, then immediately started over again. I’d read dozens of queer coming-of-age novels, dozens of bittersweet love stories, but nothing quite like this – a story of a once-in-a-lifetime love between precocious 17-year-old Italian Elio and 20-something cocksure American academic Oliver, played out over a brief six week period but recalled over and over for a lifetime.

It felt like the oldest story ever told and a freshly drawn secret, as though its writer, André Aciman, had articulated a collective memory of longing for the very first time. Its beauty lay in its diminutive moments, in its long, drawn-out descriptions of seconds-long glances between Elio and Oliver. My reaction during that first reading was almost more physical than intellectual, something more akin to a crush on a person, or a the way a heart skips during a particular key change in a pop song. It certainly wasn’t anything I had experienced reading a book before.

Before its release, Aciman was known for his nonfiction, chronicling his early life in the 1995 memoir ‘Out of Egypt’, and collating criticism on the work of Marcel Proust for the 2001 essay collection ‘The Proust Project’.‘Call Me by Your Name’ is his first novel, and it is all the more miraculous because it seemingly came from nowhere.

Since its release in 2007, the book has been a slow-burn kind of literary sensation, gaining new fans through enthusiastic word-of-mouth. Jim MacSweeney, manager of Gay’s the Word, the UK’s only dedicated LGBT bookshop, has seen the popularity of the book grow from the very beginning: “We sold a few copies when it first came out, then noticed that people were coming back to buy second copies for friends,” he tells me. “It’s always been an easy book to sell – it’s a love story, but it’s not sentimental. It captures something that we all feel but that is rare in fiction. It’s a really special book.”

It’s difficult to quantify what makes the book so special, what makes it so resonant in a sea of thousands and thousands of love stories, so much so that it has become a personal talisman for its thousands of fans. Sarah Dollard, a London-based screenwriter for Doctor Who and Being Human, and a huge fan of CMBYN, describes the first time she read the book: “It was less thinking and more… feeling. A lot. Clutching the book to my chest, tearful sighs… I read a lot of romance, about half of it queer, and most of it follows a formula. Not to sniff at formula – I only read writers who wield it beautifully. But CMBYN doesn’t do that, it is its own thing. A gorgeously written gut punch.”

This tension of physicality and emotional potency came up again and again when I spoke to other fans of the book. When Rachel Huskey, a student from Texas, first read it, she “didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, I just remember laying in bed, staring at the ceiling, and thinking about this novel for over an hour. That had never happened to me before, it just struck me so harshly in my chest and I didn’t know how to feel. My diary entry from that day says, ‘I have a fierce desire to consume this book and I don’t know how to do it.’”

When I re-read the book last year, spurned on by the announcement of the film adaptation, it was alongside two of my friends who were reading it for the first time. We would gather in a Twitter group chat every day to pore over details of each chapter, and – crucially – discuss frankly how it revealed integral truths of the possibilities of love and desire to us, which felt especially powerful in the muddy contemporary midst of casual dating and impersonal hookup apps.

One of the other participants in this informal book club, Sophie, recalls how, “every one of our interpretations and reactions to this novel was valid, vivid, and valued. Recollections of old loves, missed opportunities, the anger and disappoint of our current stumbles through the wilds of 2010s dating… This book stripped things from me that I hid from myself, it opened up what I want love – or the idea of love – to be, and how I want my muscles to burn as I reach out for it. Like Elio, looking back over that summer with each added year of wisdom and lived experience, each re-read of CMBYN feels like a space to reflect, and hone our own needs through the lens of this one specific romance.”

For all that CMBYN describes complex romantic and sexual feelings that almost everyone can match themselves up to, it’s also full of the specificities of queer experience, refreshingly removed from the constraints of a traditional coming-out narrative. Josh Winters, a writer and musician from San Francisco, recognises the importance of this for queer readers: “Many stories about young men coming to terms with their sexuality are concerned with how they navigate the “coming out” process, usually framing it as a required rite of passage (which is it not), but Aciman is purely interested in exploring how a young man comes to embrace his desire for another man removed from any idea of potential sociopolitical impact.” It’s this removal from blatantly political context that is an unspoken requirement of queer novels that makes CMBYN so refreshing.

Eoin Dara, a curator based in Dundee, addressed the duality of the universal and the specifically queer in an email to me: “The language of longing and desire and uncertainty could be about any blossoming love affair, it’s pretty expansive and universal. But then in other ways, it’s so inexplicably caught up in the invisible politics of queer desire; the politics of looking. I love how it focuses detail so minutely on eye contact in parts: Something that’s so central to queer communication – silent, unspoken understandings and messages that bounce around public space and crowded rooms full of oblivious straights.”

There’s nothing more anxiety-inducing than the anticipation of a new version of something you love so, so much – especially if its whole worth and magic lies in its atmospherics and coded glances; the most difficult things to translate to film. It’s these ephemeral details that are most anticipated among fans of the book. “There’s a lot of small things about the story that are what give the big scenes their value,” says Rachel. “The footsie, the touch during volleyball… it’s about them being so syndicated with each other that they don’t hide anything anymore.”

Jim echoes this sentiment: “Not that much happens in the book: It’s about tension, desire, longing, rather than big events. I last read it 10 years ago and I don’t even remember the character names, but what I do remember is how Aciman captures that feeling of being aware of another person in a room, and that being all that matters. And I’m interested to see how that is translated in the film.” When asked about seeing the film, Eoin confesses that “I’m so nervous about seeing it. I hope the script is sparse, I hope the looks are long.”

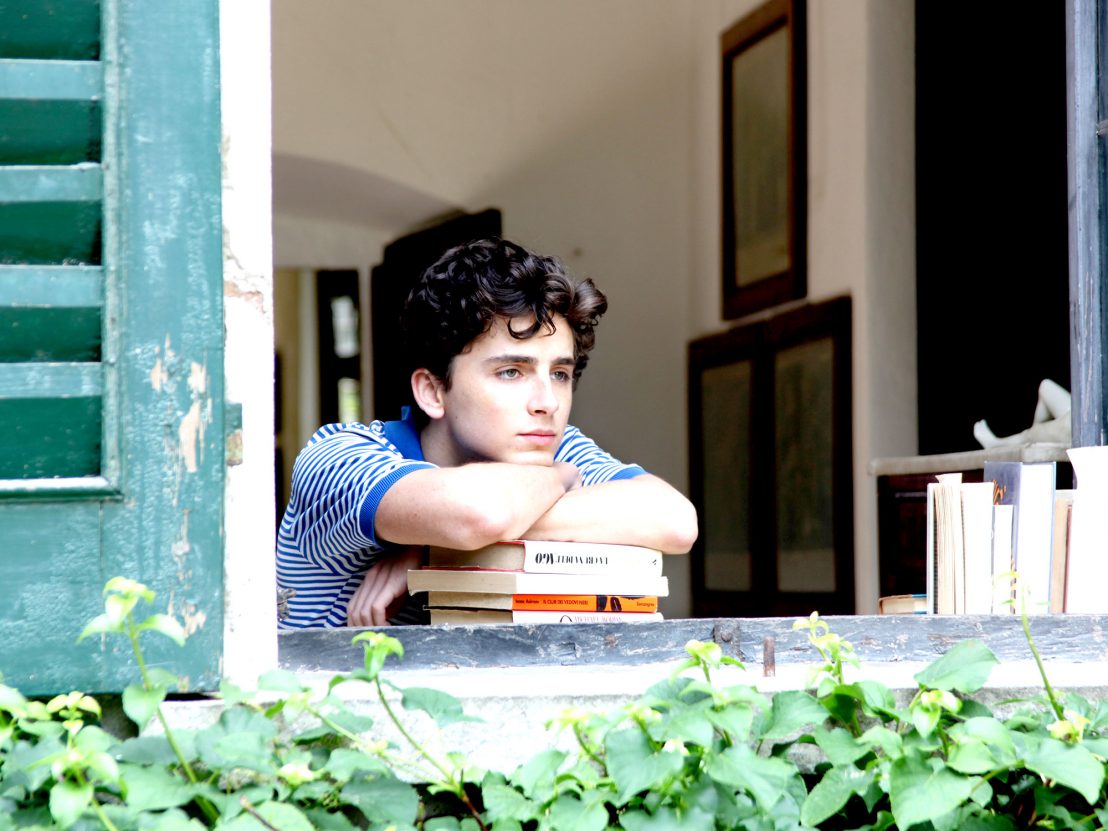

In February this year, I queued up outside a cinema at the Berlinale, shaking equal parts with late-winter cold and with nerves about seeing Call Me by Your Name for the first time. I shared the same concerns as other fans of the book: This was such a precious thing, I felt like I owned it to an extent – how could I trust anyone else to understand it so fully, to feel it so completely? But the film was wonderful, lacking some of the specific narrative details of the book but so rich with what was really important: the feeling, the atmosphere, the intangibility. It is perfectly cast and perfectly paced. I wept solidly for the last 45 minutes, feeling slightly embarrassed when the lights came up and the rush of reality set back in.

There must have been a thousand people in the packed-out cinema, but it still felt like mine. “Now that the trailers are out and the press is being done in the lead up to the film’s release, it does feel a bit like when your little secret band makes it big,” says Sophie. “But now that it’s more widespread, I still don’t have a desire to discuss it beyond my little group. I am much more fulfilled to pass an image of farmer’s market peaches, or buy an exceptionally loose and wind-swept shirt to keep CMBYN present and tangible outside of the page.”

As more and more people are drawn to the book through the film release, and through passed-on copies, word-of-mouth recommendations and informal book clubs like ours, its pages will still be there for me – for all of us – as an intimate, personal comfort, to be read and felt until early in the morning for years to come.

Published 21 Oct 2017

Our latest print edition is a love letter to Luca Guadagnino’s scintillating summertime romance.

Inspired by Todd Haynes’ Carol, explore our potted history of great films that depict gay lives on screen.

Armie Hammer and Timothée Chalamet star in Luca Guadagnino’s sun-kissed coming-of-ager.