Journey through the seedy night-time streets of London’s 1950s Soho. Past strip shows and clip joints, showgirls and women of the night. Where dancing goes on until dawn, and the jazz music never stops. All life is here.

That’s the intoxicating world at the heart of Expresso Bongo, Val Guest’s delightfully murky musical satire from 1959. It’s a film that defies convention and category. Part frothy pop musical, part satirical send-up. It’s a musical with a defiantly British sensibility.

Instead of the glitz and the glamour of New York’s Broadway, or the sophisticated romance of Paris, here our story unfolds in the scruffy espresso bars of the Soho underbelly. But inside, no ne’er do wells or underworld gangsters, just wholesome teens who want to drink Italian coffee and dance to the beat. A curiously anodyne bunch of teens really, hardly preparing to stage a rock and roll revolution.

The film stars Laurence Harvey as would be Svengali Johnny Jackson, who hangs about in the coffee bars looking for the next big thing. He discovers fresh faced Cliff Richard’s wonderfully named Burt Rudge. Burt has the voice of an angel, but he just wants to play his bongos. And you should never separate a boy from his bongos.

Sensing a path to stardom that’s paved with gold, Johnny convinces Burt to stop mingling with the “spare time geniuses” and sign a management deal as dodgy as his cheap suit. He gives Burt the snappy moniker Bongo Herbert, then proceeds to manage his career with a spring in his step and pound signs in his eyes. But the path to musical stardom is not a smooth one for Johnny and Bongo.

Adapted from his stage musical of the same name by Wolf Mankowitz, Expresso Bongo is a time capsule distilling a moment in British cultural history. It’s a playful satire of the 1950s music industry, tracking the career path of Bongo, the ‘astonishing phenomenon of our time’. Yet the exploitation of teenage crooners by seedy men out to make money from their throwaway talent is a theme that lingers eternal, with young singers tossed aside after a few hits. The TV talent shows promise riches and fame, with YouTube and internet exposure now replacing nights at the Palladium.

But the film also pushes boundaries. It features barely concealed strippers and sex shows, things that were shocking to audiences at the time. There’s a wonderful contrast between the innocence of the teens in the coffee bars, and the seedy life on the streets outside. And between Burt and Johnny who inhabit them.

Harvey seems to revel in the camp meanness of Johnny, prowling around trying to protect his prodigy with fire in his belly and a wry smile on his face. He feels like an exaggerated amalgamation of all those untrustworthy music men in suits.

Cliff is just Cliff. Young and pretty, sweet and pure. His decidedly British, latent sexuality is an advantage here. There isn’t much for him to do, just look pretty and break some hearts. A reflection of the way the young male talent was exploited at the time, and a nice change from the exploitation of pretty young girls on screen.

The women in the film are more than just window dressing. There’s a wonderfully droll turn from Yolande Donlan as fading American starlet Dixie Collins. She channels a knowing, world weary maturity as she sets her sights on naïve young Bongo. Her interest is twofold, wanting to revive her own flagging career by using him to gain a new audience, and to also take advantage of his hot young body for her sexual pleasure. There’s no pretence, we know her intentions even if Bongo doesn’t.

Sylvia Sym’s world weary stripper Maisie King is a showgirl with dreams. She has a singing voice sent from heaven, and the patience of a saint. She puts up with boyfriend Johnny and his schemes, craving stability. She takes on the role of sympathetic nursemaid to his ambitions. She does his washing, then goes to work on stage, wowing the sleazy Soho crowds.

The complexity of the two female leads is nicely complemented by the addition of Susan Hampshire’s delightfully ditzy and vacuous posh debutante, with her wide-eyed crush on Bongo, “Isn’t he sweet, isn’t he pure heaven!”

Ultimately, everyone wants a bit of Bongo. Dixie and Johnny battle for his attention and his talent, both seemingly with an unhealthy interest in more than just his career.

Despite the satirical and sleazy undertones, Expresso Bongo is a musical and the soundtrack is full of verve. From the mesmerising, jazzy opening title sequence that sets the rollicking tone for the film, to the jaunty character solo numbers, it’s pure, frothy and decidedly quirky entertainment. It almost makes you want to burst into song and open your own bongo club.

Published 8 Dec 2019

By Benjy Taylor

Lindsay Anderson’s tale of rebellion in a ’60s private school is a vital dissection of class and establishment.

By Ethan Warren

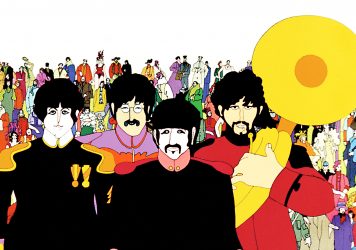

How do these psychedelic fantasias, starring The Beatles and The Monkees respectively, hold up today?

By Adam Scovell

With The Young Girls of Rochefort, the French director created something wondrously original.