One of the most revolutionary British films ever made, both in terms of its poetic discordance and as an anarchic statement at the very heart of traditional British society, If… has stood as a symbol of rebellion for generations of young people for 50 years.

In the late ’50s and early ’60s, director Lindsay Anderson was at the heart of the British New Wave, a period defined by films based largely on the novels and plays of working-class writers like Alan Sillitoe, Shelagh Delaney and John Osborne exploring the disillusionment and marginalisation of working-class youth. Anderson was at the helm for 1963’s This Sporting Life, based on the David Storey novel of the same name, which follows the traumatic psyche of a Yorkshire Rugby League player. But it is If… for which Anderson is best remembered.

In its exposition of the inner-workings of British school life, the film functions as a damning criticism of the old English public school system as a metaphor for British society and its class system. In a tiered social system, ruled over by a group of domineering prefect-like older boys known as the ‘Whips’, three revolution obsessed rebels, led by Malcolm McDowell’s Mick Travis begin to resist. They suffer the consequences of their actions, including brutal and over-excessive corporal punishment, but take their final revenge on finding a huge stash of guns in an old store room, and in an increasingly surreal climax fire upon teachers and parents from the rooftops during a Founders’ Day celebration.

It’s a film about violent insurrection, fantasy and the rebellious and revolutionary nature of sex and love that represented an English interpretation of the wave of countercultural movements building throughout the world during the latter stages of the 1960s.

The finishing touches were in fact being made to David Sherwin’s screenplay at the same time as the mass student protests in Paris, and Columbia University, as well as the ongoing and ideologically perilous Vietnam War. In the film, Travis and his friends often sit in a den-like room, which is covered in pictures of revolutionary symbols: Chairman Mao, Che Guevara and soldiers burdened with machine guns. Their conversations are not specific to the politics of their situation but reflect instead the universality of these global movements with the general rhetoric of revolution: “Death to the oppressor. Resistance. Liberty”. If… is not just a film about an English public school; it is oppressors and oppressed, resistance and retaliation and life and death.

The film won the Palme d’Or and became McDowell’s break-out role, reportedly landing him his part in A Clockwork Orange. He went on to play Mick Travis in two more of Anderson’s films, O Lucky Man! and Britannia Hospital, both partial-sequels to If… which share its chaotic and fantastical style. If… continues to resonate as a piece of anti-establishment art, in its actualisation of rebellion against oppressive systems, as well as its contextualisation of revolutionary action in a British setting.

Beyond the lasting symbolic power of the sight of Travis on the roof of the school firing at the teachers and upper-class parents, the film is more progressive in its approach to sex. In an atmosphere of intense prudishness, sex is depicted as a radical and daring expression of freedom, both for Travis and his relationship with a local waitress, and his fellow rebel, Wallace who pursues a homosexual relationship with another pupil during the course of the film. The system under which they live effectively denies the rebels of the excitement of burgeoning youth. Their rebellion is therefore not childish disobedience but a bid to be free in the way that they live their lives.

If… moves fluidly between fantasy and reality – at times without warning, or explanation. At one moment Mick bayonets the chaplain to death; the next he appears unharmed from a drawer in the headmaster’s office. Anderson arbitrarily puts large portions of the film in black and white and inserts unexplained fantastical elements throughout making you question whether anything that is happening is real or merely the wild imaginings of revolution-obsessed teenagers.

This is certainly the case in a scene that details a rare trip out of the confines of the school. Travis and his friend and fellow rebel Johnny walk into a café at which an unnamed woman played by Christine Noonan works. Mick stirs his tea provocatively (as English a rebellion as any), before she approaches him, sizes him up and says, “Sometimes I stand in front of the mirror and my eyes get bigger and bigger. I’m like a tiger. I like tigers.” The two begin clawing at each other like wild animals, and as they grapple and roll around the floor, shots of them naked are interspersed. Using experimental and surrealist devices, Anderson manages to explore both the reality of the situation, and what lies beneath: the animalistic energy of the teenage libido.

Published 19 Dec 2018

By James Oddy

Lindsay Anderson’s exhilarating look at the psyche of rugby league player has lost none of its emotional punch.

By Adam Scovell

Visiting the southeast London estate featured in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film makes for a dystopian experience.

By Sam Thompson

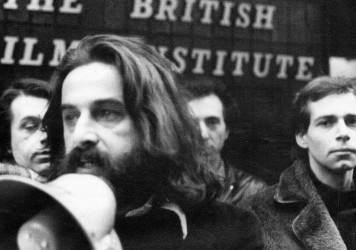

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.