The director’s astonishing 1969 film was shown from the only known 35mm print in existence.

For film lovers, there is little more tantalising than the prospect of seeing the unseeable. Those holy grails known to exist but rarely screened; discoverable only in barely-watchable, taped-off-the-telly .avi files from the more questionable, laptop-obliterating corners of the internet. Until a few years back, this was the only way to see Jacques Rivette’s Out 1, a film described in hallowed and hushed tones by those malware-averse enough to seek it out. Like many others, my first encounter with the film took a well-trodden path: an illicit USB-stick palmed by a pal with a look of ‘this is good shit’ knowingness.

I’d first heard about the film following its debut UK screening (some 35 years after it was completed) as part of the National Film Theatre’s Rivette retrospective back in 2006. Of course, after-the-fact was too late for a ticket, but I took what consolation I could in a first exposure to the self-proclaimed ‘éminence grise’ of the Cahiers-clan with the re-release of his more approachable 1974 masterpiece, Céline and Julie Go Boating.

There was no getting away from the fact that the grim, lo-fi resolution of that first Out 1 viewing abetted the thrill, the film’s mythological status compounded by a running time that pushed 13 hours. Now, of course, there’s no such need for piratic subterfuge, given the god-bothering work undertaken by Arrow Films to bring this little-seen epic to UK and US audiences.

As any child of the ’80s with a BBFC-disapproved checklist of the era’s video nasties could attest, it’s a rare missing-in-action title that lived up to the promise of its ‘Here Be Dragons’ cultural status. But Out 1 was one such film, an unforgivingly experimental work of serpentine narrative structures and conspiratorial cul-de-sacs that demanded the repeat viewings and deep immersion a home video release could afford.

Of course, one of the great accompanying benefits to such an important release was the wealth of contextualisation and assessment that followed in its wake. The ready availability of one of the key works of one of the great directors meant an entire career could now be afforded a complete sense of perspective.

Well, almost.

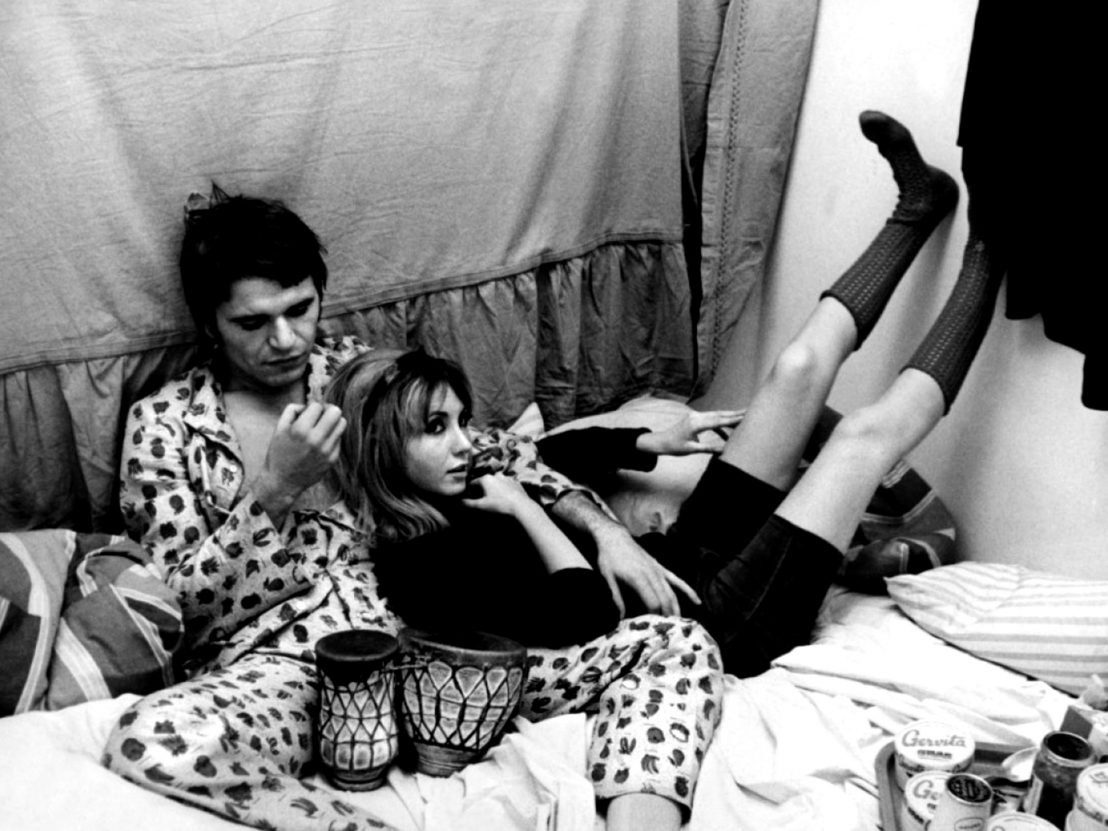

Perhaps it’s the less impressive running time (a mere 252 minutes) that prevented L’Amour Fou from being spoken of with the same awed reverence as Out 1. Released in 1969 – two years before its all-consuming younger brother – the film has never been available on home video. It comes and goes from YouTube in a low-quality, badly-subtitled rip from French television, a viewing experience that does neither film nor viewer any favours. On Friday 4 August, as part of a stunning retrospective of Rivette’s work, the New Horizons Film Festival in Wrocław, Poland played the only 35mm print of the film known to exist. It was as filthy and scratched as one might expect a US release print with burnt-in subtitles to be, but the screening proved a revelation.

L’Amour Fou is the missing link in Rivette’s filmography, in many respects the key to unlocking and better understanding Out 1’s myriad mysteries. Not that the earlier film represents a work-in-progress en route to the latter. If anything, it’s the more hermetic of the two works, and certainly the more emotionally direct. It’s also, for my money at least, the director’s greatest film.

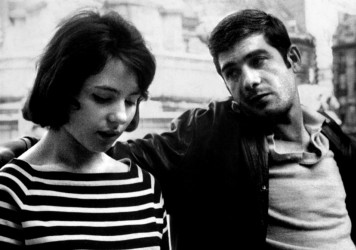

Following the protracted production difficulties of his 1961 debut feature, Paris nous appartient, Rivette took a more traditional approach for his 1966 follow-up, The Nun. Working from his own adaptation of Denis Diderot’s novel of the same name, new frustrations arose from the inflexibility of a script-based working method. As Mary M Wiles recounts in her excellent contextual analysis for Senses of Cinema, it was an encounter with Jean Renoir that set Rivette on the freeform path that would come to define his greatest works.

The plot of L’Amour Fou is straightforward enough, but gives little sense of its cinematic strategies. Sébastien (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) is directing a theatrical production of Jean Racine’s 17th century classic, ‘Andromaque’, while also playing the lead role of Pyrrhus. His wife, Claire (Bulle Ogier) – cast opposite him as Hermione – walks out on the show at the start of the film, perturbed by the intrusive presence of a documentary crew filming rehearsals for television. Sébastien recasts her part with an ex-girlfriend, Marta (Josée Destoop), leaving Claire at home to slowly unravel at the thought of her former castmates and company conspiring against her.

“Life and theatre get a bit too intertwined, eh?” asks the documentary filmmaker early on. It’s the question at the heart of L’Amour Fou, as Rivette steadily deconstructs the nature of performance and excavates the inherent tensions between lives lived on and off stage. His method is at once brilliantly simple in conception and infinitely complex in execution, intercutting 16mm footage of the rehearsals with a more objective, 35mm eye on the wider narrative.

Jean-Pierre Kalfon was given free rein to stage his own production of ‘Andromaque’ without Rivette’s interference, as was real-life documentary filmmaker, André Labarthe, here ‘playing’ himself. So Rivette films Labarthe filming the rehearsals that make up extended portions of the film, just the outer circle of L’Amour Fou’s many levels of reflexivity.

“TV perpetuates the myth of the director,” says Sébastien of Labarthe’s film-within-the-film. With three directors at play here, Rivette’s method asks questions of authorship and responsibility within his own wider scheme, just as Sébastien asks questions of the stage. “What is theatre?” he wonders, “A game of masks that bares the condition of the soul… It lets spectators judge one character against another through their own subjectivity.” The stage itself appears to act on those who act on it, Rivette framing its vast whiteness as a looming, mystical presence. A cast member asks her director if he was happy with the day’s work before a stunning cut to the stage and back – replete with the sound of a slamming door – gives a split-second impression of sentience, of a living organism under their feet.

Soon enough, the emotional devastation wrought in Racine’s play becomes mirrored in Claire and Sébastien’s relationship, culminating in the tour de force of the film’s final hour. With Claire threatening to leave him, Sébastien takes a razor blade to his clothes. As the pair sink into a manic state of shared psychosis the relationship finds its last hurrah in the obliteration of their apartment.

It’s a film of deep paranoias, as one might expect from Rivette, perhaps. But where Paris nous appartient and Out 1 cast their conspiracy theories outwards into a spiralling series of endlessly regenerating MacGuffins, L’Amour Fou’s neuroses crumble inwards. For all Rivette’s meta shenanigans and prolific formal enquires, there’s a piercing sadness to Claire’s destruction – and ultimate liberation – that transcends all intellectual concerns.

Stuck in her flat, recording lines from the play she’s quit (as her replacement speaks them onstage), her sense of self begins to deteriorate as we become more privy to her husband’s affairs. It’s a stunning performance by Ogier, exacerbated by Rivette’s rare close-ups. Her escape from the shackles of an abusive marriage becomes the film’s emotional climax. Sébastien’s reading of the end of Andromaque (“He loses feeling while the other is insane already”) sounds like he’s talking about his offstage life, but it’s a purely subjective perspective; indicative of his own negligence, what he calls out in Racine’s Pyrrhus as a “moral flabbiness.”

It’s a film crying out for the stellar restoration work afforded Out 1. Whether said undertaking comes down to a question of rights, available materials or financial commitment is anyone’s guess. I can’t wait for the readings such a release would afford when it does finally re-surface. The film’s astonishing devices and enquiries – the way the two formats interrogate their subjects and each other; the tensions between the rigidity of text and fluidity of improvisation; between language and the body; the astonishing soundscapes and editing schemes – are all deserving of essays of their own. It’s a ‘lost’ masterpiece if ever there was one.

The Jacques Rivette retrospective is at the T-Mobile New Horizons Film Festival until 13 August. L’Amour Fou screens again on 12 August.

Published 7 Aug 2017

This early work from the French New Wave icon is a must-watch for cinephiles.

By Adam Cook

The late French master’s first film, Paris Belongs to Us, is now available courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

By Matt Thrift

This year’s AFF ended with an eye-popping cinematic spectacle – a film unseen for 50 years.